10 Questions for sound designer Adam Cork | reviews, news & interviews

10 Questions for sound designer Adam Cork

10 Questions for sound designer Adam Cork

Meet the sound magician behind 'Enron', 'London Road' and now Yaël Farber's 'Salomé'

No one ever went to the theatre for the sound design. Indeed, only the nerdiest theatregoers could name a single practitioner of the art. But imagine attending a production by Katie Mitchell or Robert Icke or Ivo van Hove – or any less overtly authorial theatremakers – with the sound design stripped out. The visual story would be immeasurably impoverished.

Thus it is with Salomé. The National Theatre’s new production is the work of Yaël Farber: the visionary South African director has gone back beyond Strauss and Wilde to the sparse biblical sources to tell the story of the princess in Herod’s court in occupied Judea who asked for the head of John the Baptist.

The imposing sound design and musical composition is by Adam Cork, who has put together a sort of sound opera which richly meshes Arabic and Hebraic vocals, propulsive percussion, and the strains of western classical music, all underpinned by the droning backdrop that is now a feature of contemporary theatre.

Cork, 42, is most associated with the work of Rupert Goold and Michael Grandage. For the former he wrote the songs that popped in Enron. Although originally a composer, he has only a stage musical on his CV, but it’s a ground-breaker: London Road, Alecky Blythe’s verbatim musical about the Ipswich community convulsed by the murder of five sex-workers, which was later made into a film. He tells theartsdesk about the obscure art of designing sounds.

JASPER REES: Is the function of sound design to work on the audience subliminally?

ADAM CORK: I’d say that’s one of its functions. Obviously it can have a scenographic function. If you need to establish place quickly and sharply, sound can help, especially if you don’t have a huge set budget or don’t want lots of clunky scene changes. In Salomé there is the subliminal thing. I don’t know if our two wonderful singers count as sound design but it can surge into the foreground sometimes and carry the experience of the audience forward in a ritualistic way. There is something about it that is non-literal, and if you do it in the right way the audience are experiencing it on a more primal level.

The two singers – Lubana Al Quntar and Yasmin Levy (pictured below) – are our introduction to the world of Judaea. How did you alight on the intoxicating sound palette they provide?

Yaël completely bypassed Strauss and Wilde and went back to the very minimal information that exists of Princess Salomé and created her own rhapsody from her own obsessions around this woman. I haven’t listened to the Strauss at all. Lubana Al Quntar is our Syrian singer who sings the traditional Arabic and is also a trained soprano in the western tradition. Yasmin Levy is from the Sephardic Ladino tradition that harks back to when the Jews were in Spain and Portugal before they got kicked out in 1492. She sings very oriental-sounding melodies that most Spaniards wouldn’t necessarily be able to understand, but also in Hebrew. There are no surtitles for their words, unlike for Iokanann aka John the Baptist. What words are they singing?

There are no surtitles for their words, unlike for Iokanann aka John the Baptist. What words are they singing?

Lubana is singing, “You go away / My scream is fading in the valley where there is no echo.” That is throughout the piece and is developed and speaks to Salomé being violated by Herod, and her people being colonised by the Romans. Yasmine sings, “Come, dear, come, love / Let’s go to the sea / I’ll tell you my sad story / I’m an orphan / The only good dream I have in this life is the dream to die in your arms.” Those two songs seemed to have a concordance which we found surprising and beautiful.

Another potent effect is the propulsive percussion and the constant throbbing background drone. It’s as if a tube train is running under the theatre for the entire show.

The percussion helps to give the plot a momentum but also conveys a sense of the epic scale of the ancient world. Drone-based sound-scores are a language that over the last 15 years I’ve come to embrace if the story is right for it. Drones can be many things. They can be threatening for sure, but they can be warm, supportive and they can be neutral and enclose the drama in a texture which ideally doesn’t interfere with the dialogue. But I don’t think all plays should have them. Absolutely not.

Are the roles of composer and sound designer increasingly indissoluble?

I don’t think they are, no. They are two very different fields of expertise. There are a few of us who do both. There was a time a few years ago when some feared that unless they did both they were going to be on the rubbish tip. That was rubbish itself. There is still a need for specialists in both those areas. It was just something I fancied doing. I started out as a theatre composer and realised I really enjoyed having control over every aspect of the sound score. So I learnt a bit about how to do pre-recorded sound design and really loved it. But there is a whole other side to sound design which is about serving a room and amplifying actors. You need to know what you’re doing and for a while I didn’t.

I don’t think they are, no. They are two very different fields of expertise. There are a few of us who do both. There was a time a few years ago when some feared that unless they did both they were going to be on the rubbish tip. That was rubbish itself. There is still a need for specialists in both those areas. It was just something I fancied doing. I started out as a theatre composer and realised I really enjoyed having control over every aspect of the sound score. So I learnt a bit about how to do pre-recorded sound design and really loved it. But there is a whole other side to sound design which is about serving a room and amplifying actors. You need to know what you’re doing and for a while I didn’t.

Is augmentation of actors’ voices a creeping reality of theatre?

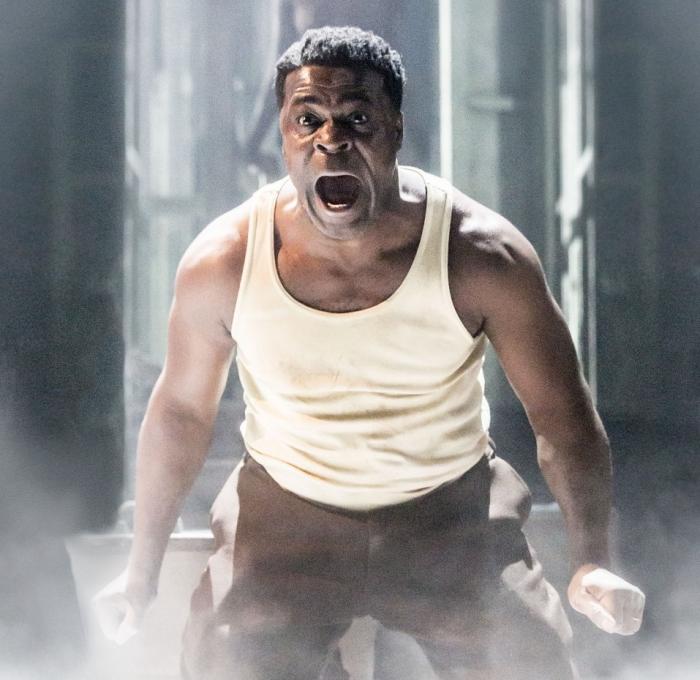

When you do put microphones on actors for artistic reasons there is always some tension from some members of the acting company. They think it’s a creeping thing that all actors will have to be miked, and they hate it. Also they hate it when it’s done badly because they feel they’re got no control over how they’re reaching an audience. I’m very sensitive to that. With Salomé and last year’s Les Blancs (Danny Sapani pictured above by Johan Persson) we put mics on the actors because we knew there would be am ongoing and sometimes very present sound score that they sometimes would have to fight. Also we wanted to add special effects which we could only do if an actor’s got a mic. That’s not about making them louder; that’s just about putting them in a particular acoustic. Their naked voice is still reaching the audience under their own power. Some actors are so unhappy at wearing microphones that you have to rethink. Where did you start?

Where did you start?

My mum bought a piano when I was six and I starting plonking away, apparently tunes I’d heard on the telly. I got more formal piano lessons and eventually I got one of those local council bursaries and ended up going to the Royal Academy every Saturday morning throughout my teens. Then I went on to study music at Cambridge. It was a very academic course but that has really helped me as a composer. After uni I did a bit of assistant directing on smaller-scale operas and I had an interview at Glyndebourne for one of the staff director jobs but then at the same time Rupert Goold asked me to write the music for a production of The End of the Affair at Salisbury Playhouse studio. That seemed the more attractive option. I do not know to this day if Glyndebourne were going to take me on or not.

How was Enron (pictured above by Tristram Kenton) explained to you by Goold? “We’re doing a play about a financial scandal, it’s not a musical but there will be songs.”

Nobody ever sits down and says that. There have been songs in plays for hundreds of years. A lot of them were written to cover awkward scene changes. Now they’ve become a way of carrying the story forward. With Enron there was one section where Lucy [Prebble, the playwright] had said, “The traders come out and they sing.” I ended up writing vocal lines which were like financial graph lines, I like to think. They fluctuate and go up and down unpredictably in a way that makes you feel unsafe. We all enjoyed the Commodities Chorus so much that Rupert said, “Let’s have a 9/11 chorus as well.” And we had our bankers doing a barbershop quartet. We only have three songs but people remember the moments in theatre. London Road (pictured above by Helen Warner) is the only show of yours that one would more than tentatively classify as an actual musical. Did you discover new things in yourself as a composer that you didn’t know about?

London Road (pictured above by Helen Warner) is the only show of yours that one would more than tentatively classify as an actual musical. Did you discover new things in yourself as a composer that you didn’t know about?

Listening to recordings of people speaking spontaneously and turning those transcriptions into songs – that process spoke to a very nerdy side of my brain that likes intricacy and complexity. It took me a while to get back to doing incidental music that served the drama without getting in the way. It was wonderful to be the author of the whole of my own work together with Alecky Blythe and, yes, I long for that experience again. But it’s very very difficult to write a good musical.

- Salomé is in repertoire at the National Theatre until 15 July. It is broadcast to cinemas by NT Live on 22 June

- Read more theatre interviews on theartsdesk

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

Add comment