Classical CDs Weekly: Chopin, Glass, Alec Frank-Gemmill | reviews, news & interviews

Classical CDs Weekly: Chopin, Glass, Alec Frank-Gemmill

Classical CDs Weekly: Chopin, Glass, Alec Frank-Gemmill

Polish dances, minimalist piano music plus multiple horns

Chopin: Mazurkas Ivana Gavric (Edition Classics)

Chopin: Mazurkas Ivana Gavric (Edition Classics)

Ivana Gavric suggests that Chopin’s Mazurkas are “short, poignant, diary entries”, and her performances remind us how the greatest composers are never constrained when writing miniatures. As with Bartók’s vast Mikrokosmos, where the simplest, sparest studies sound fully realised. Gavric sticks to mazurkas composed before 1838, preferring their unmannered rusticity. It's a shock to read a critic in 1833 describing Chopin's Op. 7 set as containing “ear-splitting discords, harsh modulations, ugly distortions of melody and rhythm”. Gavric understands that these are dance pieces; the rhythms have plenty of lift, and there’s just enough rubato to titillate without making things sound sickly.

The early Mazurka in F minor demonstrates just how good Gavric is, Chopin’s more arresting chord progressions played teasingly and hesitantly, as if she's making them up on the spot. The minor key numbers are especially effective, Op. 34’s moody C sharp minor Mazurka another standout. Gavric can also do folksy charm: Op. 33’s D major number is an unpretentious peasant stomp with a wonderful payoff. Extras include a pair of lesser known Preludes and a melting Op. 57 Berceuse. Gorgeous recorded sound and handsome presentation.

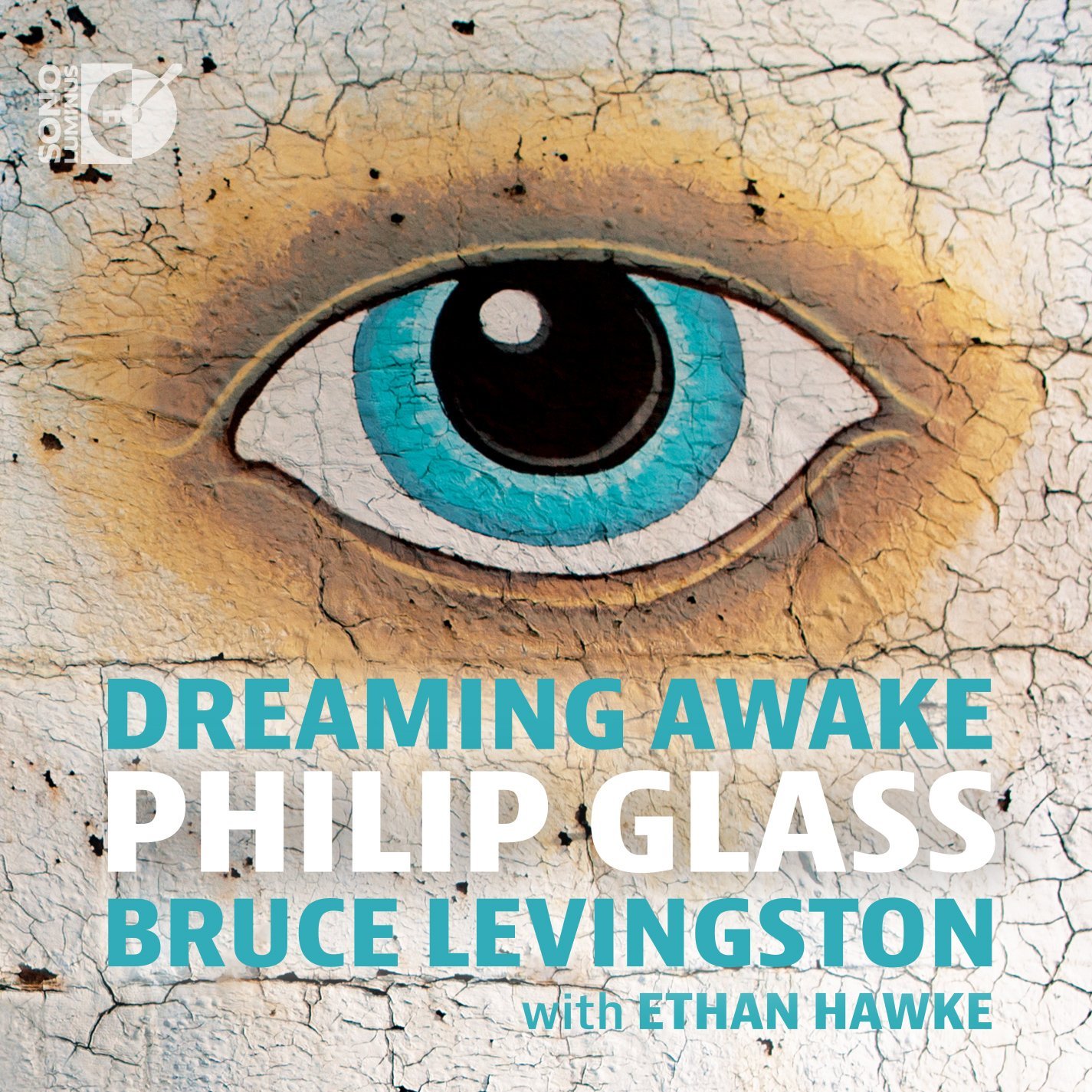

Glass: Dreaming Awake Bruce Levingston (piano), with Ethan Hawke (Sono Luminus)

Glass: Dreaming Awake Bruce Levingston (piano), with Ethan Hawke (Sono Luminus)

Philip Glass’s reputation seems to have dipped a little as the careers of Steve Reich and John Adams have soared. I can't quite work him out; I've enjoyed ENO’s staging of Akhnaten twice, but couldn’t get on with his odd, proto-Brucknerian symphony based on Bowie’s Heroes album. But this collection of shorter piano pieces is a revelation, suggesting that Glass hits the mark consistently when composing on a smaller scale. His ongoing series of Études for solo piano were written to develop his own technique. They're pure, distilled essence of Glass. If you're an affirmed sceptic, you won’t be for turning, but doubters will be converted. Sample 2012’s No 17, a catchy, smoochy rumba in 7/8, or the Bach-referencing opening to No 2. The slower numbers are deeply affecting; No 5 a memorable highlight.

The familiar Glassian tropes pop up again and again throughout this anthology. Minor thirds and arpeggio figures jiggle, and duplet rhythms clash with triplets. But they’re always a means to an end, serving a very pianistic imagination and an abundance of good tunes. These études charm, entertain and move by turns. Glass’s friend and collaborator Bruce Levingston commissioned several of them, and he’s a persuasive, expansive guide. The dexterity and accuracy are thrilling (as in No 6’s quickfire repeated notes), but what impresses is Levingston’s irrepressible enthusiasm, gleefully highlighting Glass’s debts to Bach, Chopin and Schubert. I've had these discs on regularly for several months and I'm still enjoying them.

At some point Levingston needs to record the full cycle of Études. Until then, we get a diverting suite drawn from Glass’s score to the film The Illusionist, as well as a Kafka-inspired piece which turned up on the soundtrack to Errol Morris’s The Thin Blue Line. More importantly, there’s Wichita Vortex, the piano accompanying a speaker reciting an Allen Ginsberg poem. Speech and music aren't always happy bedfellows, but this works a treat. A rambling, discursive paean to love and happiness, the words are intoned in some style by Levingston’s long-term acquaintance and near-neighbour Ethan Hawke. The pair perform as if their lives depend on it, the collective positivity oozing out of the speakers. Wichita Vortex’s optimism alone makes this a mandatory purchase. Sono Luminus's production values are predictably high. An essential Glass anthology, with appealling sleeve art.

A Noble and Melancholy Instrument: music for horns and pianos of the 19th century Alec Frank-Gemmill (horn), Alisdair Beatson (piano) (BIS)

A Noble and Melancholy Instrument: music for horns and pianos of the 19th century Alec Frank-Gemmill (horn), Alisdair Beatson (piano) (BIS)

Horns and pianos really, as, between them, Alec Frank-Gemmill and Alisdair Beatson use a total of eight different instruments on this recital disc. The logistical and organisational challenges must have been immense, but the musical results are glorious. Frank-Gemmill’s booklet note compares the piano's relatively straightforward technical evolution with that of the horn: valves enabling the easier playing of chromatic scales arrived early in the 19th century but weren't adopted readily by all composers. Brahms preferred the sound of the natural horn, whereas Schumann adopted a more pragmatic approach. His Adagio and Allegro is featured here, performed on a 19th century Viennese valved horn with Beaton accompanying on an 1847 piano. Fiendish enough on a modern instrument, Frank-Gemmill’s fearless, colourful playing on an antique single horn paradoxically makes the piece sound easier. The same combination of instruments is used in the lovey Notturno by Richard Strauss’s horn-playing father, Franz. Beethoven's ungainly Horn Sonata sounds far less intractable when played on a vintage hand horn with fortepiano, and it’s good to hear a similar instrument played with such skill in short pieces by Rossini and Saint-Saëns.

An early 20th century piston-valved horn is combined with an 1898 Bechstein in music by Glazunov, Dukas and Vintner. Dukas’s test-piece Villanelle is the pick of the three. Frank-Gemmill scrupulously follows the composer's instructions, sticking to the natural horn in the slow opening section. The switch to valves as the tempo hots up is remarkable; it’s as if we’ve arrived in the 20th century. As a bonus, the pair throw in a typically anachronistic piece of English fluff: Gilbert Vintner’s Hunter’s Moon was a favourite of Dennis Brain. Written as late as 1942, it's an inconsequential delight, the sizzling handstopped notes a highlight. Unmissable, with Beatson an unfailingly sympathetic accompanist.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

Willis-Sørensen, Ukrainian Freedom Orchestra, Wilson, Cadogan Hall review - romantic resilience

Passion, and polish, from Kyiv's musical warriors

Willis-Sørensen, Ukrainian Freedom Orchestra, Wilson, Cadogan Hall review - romantic resilience

Passion, and polish, from Kyiv's musical warriors

BBC Proms: Faust, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Nelsons review - grace, then grandeur

A great fiddler lightens a dense orchestral palette

BBC Proms: Faust, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Nelsons review - grace, then grandeur

A great fiddler lightens a dense orchestral palette

Add comment