theartsdesk Q&A: Director Michael Longhurst | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Director Michael Longhurst

theartsdesk Q&A: Director Michael Longhurst

The stellar young theatremaker who is suddenly everywhere

Is there more than one Michael Longhurst? As sometimes happens in theatre, a rising young director seems to be everywhere at once. His calling card is the modestly universal Constellations. Directed with clarity and simplicity, Nick Payne’s romantic two-hander with multiple narratives has travelled from the Royal Court via the West End to New York, before touring the UK and heading back to London this week.

And if that’s not enough Longhurst to go around, there’s always Bad Jews, Joshua Harmon’s savage comedy about identity imported from America, which landed here at the St James Theatre and continued at the Arts. The director’s recent CV also includes Carmen Disruption at the Almeida, in which he conjured up a thrilling theatrical spectacle out of the bare bones of Simon Stephens’s text. At the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, he took the chance with his first ever classical production to have fun interrogating Ford’s ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore.

Churchill’s questioning examination of the nascent cloning industry was premiered in 2002. It features a father and three identical sons, two of whom are clones. They were first played at the Royal Court by Michael Gambon and Daniel Craig. Since then it has become the preserve of real fathers and sons. Timothy and Samuel West have twice tackled the play – in Sheffield and at the Menier Chocolate Factory – and now John and Lex Shrapnel return to it. Longhurst first directed them at the Nuffield in Southampton last year. The Young Vic revival is no mere clone, however, as Longhurst explains to theartsdesk.

JASPER REES: This production opened in Southampton last year. How much rehearsal have you needed again?

MICHAEL LONGHURST: When we knew the revival was going to be happening we gave ourselves a couple of weeks’ rehearsal mainly because Churchill’s play is an incredibly tricky learn. Her punctuation is so precise. I didn’t know what we’d still have a year later. I’m excited to report that John and Lex have kept the lines there so we can spend the two weeks trying to deepen the ideas of the play, explore ideas that we glanced at last time. We’ve had Caryl in this time so we’ve had some new steers to dig into.

What does she bring into the room?

It’s incredibly exciting to have Caryl there. It’s Caryl Churchill! What she does so brilliantly, and this is a sign of her security in her work, is she is incredibly aware of where there is ambivalence in her writing and therefore able to offer steers in terms of what she meant. And she is very up for engaging with our imaginative back stories that we’ve created for the characters for the scenes. It’s an opportunity to bounce ideas off her.

This play was first performed with Daniel Craig and Michael Gambon and then the Wests did it. What is it that having a father and a son act opposite each other brings to this play about fathers and sons?

An undeniable frisson from hearing someone say, “No, I am really your father. I am genetically your father.” There are huge sections where paternity is absolutely debated and fundamentally the play is asking, what makes us who we are? It explores the nature vs nurture argument. To have that living embodiment in front of you is very exciting.

A lot has happened in the world of cloning since 2002. Dolly the Sheep feels like Dolly the Dinosaur now. How do you deliver the play to a more knowing public?

It’s possible to do A Number as a very sci-fi dystopian exploration of what might happen. Fundamentally we haven’t started cloning humans in the last 10 years but the joy of what Caryl does is she takes a scenario only just beyond our capabilities. Huge steps have happened. We can edit the human genome now which means that theoretically we are on the way to being able to eradicate hereditary diseases but also selectively edit our genes which could lead to all kinds of things. So distinctly ethical questions surrounding what we should do are more present the nearer it feels.

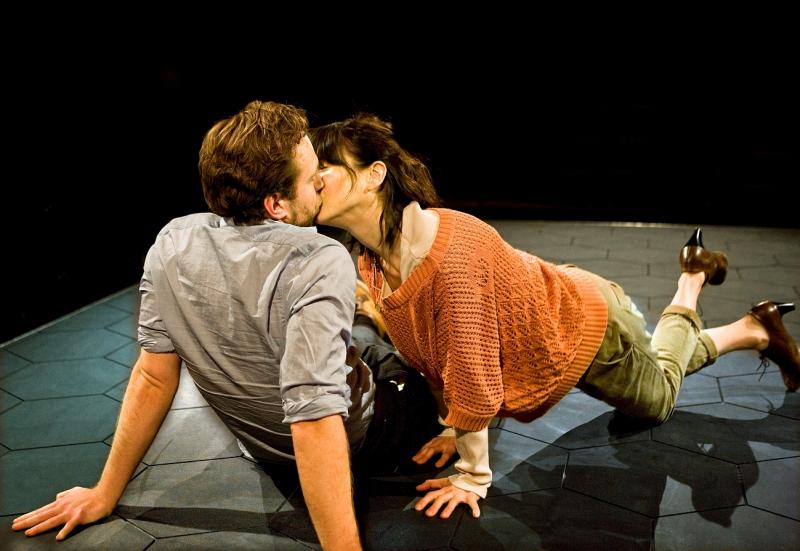

Constellations has been an extraordinary success. What is it about that play and your part in it that has touched a nerve? (Pictured, Rafe Spall and Sally Hawkins. Photograph by Simon Annand)

Constellations has been an extraordinary success. What is it about that play and your part in it that has touched a nerve? (Pictured, Rafe Spall and Sally Hawkins. Photograph by Simon Annand)

Fundamentally the play is a boy-meets-girl love story. Nick wrote the play at quite a specific time in his life. He met his future wife at the same time as he was losing his father. So those ideas of love and loss are huge human emotions that have a real presence in Constellations. There is a real gamut of emotion explored from humour to heartbreak. And I think structurally Constellations plays into the could-have-beens, the should-have-beens, the might-have-beens, which is part of our humanity: wondering what our lives might have been if we’d turned left rather than right. Nick really understands loss. He’s written beautiful scenes for amazingly talented actors. Each actor has taken their turn through the multiverse, and revealed some of themselves and audiences have been really inspired by that.

What happened to the play between London, where it starred Sally Hawkins and Rafe Spall, and New York, where you directed Ruth Wilson and Jake Gyllenhaal?

We explored for a while the idea that we might do an American version of it but actually it felt there was something inherently British in the way the characters date, in the way they are self-deprecating, in the way they aren’t direct like Americans often are. There was that exploration. American audiences receive it in a different way. That nod of recognition is stronger in the UK. So it’s very exciting to see it playing back here [with Joe Armstrong and Louise Brealey, pictured below. Photograph © Helen Maybanks]. But essentially the play is a love story so it trades on the chemistry of whoever the two people are that are exploring that story. So it had a different feel and chemistry about it in New York. It was seen as a very experimental play there whereas it’s one of the most commercial things I’ve done. It’s a very unusual play for Broadway, not to be set in a living room, not to have a chaise longue, to have nothing.

Is there any thematic link beyond your involvement in the following three titles: Bad Jews, ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore and Carmen Disruption? (Pictured: Jenna Augen, Gina Bramhill and Ilan Goodman in Bad Jews. Photograph by Robert Workman)

Aha. No. No I don’t think there is. As a freelance director, to some extent you’re a gun for hire and you’re subject to the offers that people put in front of you. And something I love as a director is being challenged by new types of material. ‘Tis Pity is the first bit of classical directing I’ve done. Bad Jews I sort of had an affinity with because when I did a previous show in New York it was below us and my play had a 25,000 gallon flood that flooded onto their stage. I never actually saw it. I felt I had a duty to read the play and engage with it. I guess there are questions of identity in all of them. I’m incredibly grateful that Dominic Dromgoole offered me a chance to have a go at classical repertoire. Having seen my new work, that was a leap of faith.

Why hadn’t you directed anything classical until then?

Why hadn’t you directed anything classical until then?

As a young director you’re very conscious that nobody needs to see your version of whichever classic it is. Nobody needs to see a 21-year-old’s Hamlet. I wouldn’t have been ready to do it. I didn’t have an interest in doing it. I got into directing new plays through working at the Edinburgh Festival. It felt like the way you could get the most attention as a young company performing a new play was if the work was of topical social significance. In Edinburgh I did a play the first time about immigration and the second time about the Iraq war. That did a lot better than my Equus which was up there the year before. That bred in me a taste. I learned about the pages that you’d skip over in a newspaper when someone offered me a play about them. There is something vital about telling stories about the world we’re in now and it developed muscles as a director to help give a platform for new plays and the dramaturgy that surrounds that and helping writers shape their work and get their stories to where they want them to be. And there was access to material. There were writers that wanted their work staged. As I have developed as a director there is a certain amount of auteurship that comes in at a certain stage. ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore is one of the first times I’ve not had a writer in the rehearsal room. So it was quite a different experience to be surmising what John Ford meant 400 years but also enjoying the fact that I could have the final say. With most revivals you have to be so sure that you’re bringing something fresh, that there’s a reason for reviving it. Otherwise the danger is you’re creating a museum piece that is not in conversation with the audience now and the world we live in. (Pictured: Fiona Button and Max Bennett in 'Tis Pity She's a Whore. Photograph by Simon Kane)

Part of bringing back A Number was we could push the design a bit. We’ve got somewhere very different this time. Tom Scutt and I knew that we wanted to move the production forward and not repeat ourselves and Tom’s very radical offer of a solution was to place the action inside a two-way mirrored box. So we as an audience experience it through a two-way mirror. It felt like in a single gesture he had absolutely nailed the themes of the play and presented a very different way of experiencing the play. My job as a director was to be brave and decide whether or not the joy of live theatre is you’re sharing the same area with performers. That’s not going to be the case this time. I felt that in a play that’s asking about identity, to use mirrors is a very simple but beautiful way of exploring that. The audience experience is a bit like looking at a police line-up, which brings up the idea of responsibility, which is actually is the deepest theme in the play. The play is asking about free will; are we responsible for our actions? Given we might be predisposed to behave in a certain way because of our character, whether that’s nature or nurture, in what sense are we truly autonomous?

Part of bringing back A Number was we could push the design a bit. We’ve got somewhere very different this time. Tom Scutt and I knew that we wanted to move the production forward and not repeat ourselves and Tom’s very radical offer of a solution was to place the action inside a two-way mirrored box. So we as an audience experience it through a two-way mirror. It felt like in a single gesture he had absolutely nailed the themes of the play and presented a very different way of experiencing the play. My job as a director was to be brave and decide whether or not the joy of live theatre is you’re sharing the same area with performers. That’s not going to be the case this time. I felt that in a play that’s asking about identity, to use mirrors is a very simple but beautiful way of exploring that. The audience experience is a bit like looking at a police line-up, which brings up the idea of responsibility, which is actually is the deepest theme in the play. The play is asking about free will; are we responsible for our actions? Given we might be predisposed to behave in a certain way because of our character, whether that’s nature or nurture, in what sense are we truly autonomous?

How did you get into this game? What led you to become a director?

At school I used to act and used to think I was quite a good actor. I was Joseph in Joseph, and Jesus in Godspell. And then I went to university to do philosophy and was suddenly fifth spear-carrier in the drama soc and discovered I was actually a terrible actor. I got into directing student theatre. There were some very talented people like Ruth Wilson at university. I studied art and I nearly went to art college and I used to design my shows originally. I think that is a thread that runs through my work: the visual aspect is very important to me. When I didn’t get cast in something one term I had a go at directing. And it suddenly felt that that worked much better. There is a moment where you give an actor a good note and something amazing happens. There is a collaborative thing in directing. I knew I didn’t want to be a painter on my own in a shed.

Did you start almost immediately?

I worked in the City for a year and then I went to Mountview and did a postgrad in directing and then I bounced around the fringe in London. I’ve had a career of entirely freelancing. I’ve not been attached to buildings. I put a play on in a pub and then a slightly bigger pub offered me another play.

Could you see yourself being attached to a building or is that simply not you?

I am in a position now where it’s very empowering to be able to choose between freelance offers, to really try and find work that I think will really challenge me. I hope that I might get involved in a building at some stage just because actually when someone books you to do a job they’ve committed to a play usually, they’re confident they’re going to be able to bring an audience to it and my job is to entertain them for that hour and a half. To be part of that cultural conversation earlier and higher up is appealing – why we make theatre, what we hope theatre can do by the programming of a season. I’m excited that I’m getting to work on more stages, on more challenging plays.

Which segues neatly into Carmen Disruption. How much was actually there on the page from Simon Stephens on the first day of rehearsal? (Pictured: Sharon Small in Carmen Disruption. Photograph by Marc Brenner)

Which segues neatly into Carmen Disruption. How much was actually there on the page from Simon Stephens on the first day of rehearsal? (Pictured: Sharon Small in Carmen Disruption. Photograph by Marc Brenner)

On the page there are no stage directions and on the page it was a monologue play with an undefined chorus. But what Simon had done is give me the whole of the history of Carmen as source material. And so I decided it’s a story about a singer who doesn’t sing. But fundamentally you want the music of Carmen. Simon is also exploring the transcendence that music can provide, so I was looking for a way to put music at the heart of the story while having a narrative in which the singer doesn’t sing, which is where my idea came from that the chorus could be the spirit of Carmen looking for an avatar, as it were. And that was the basis for the production. It was so joyful to have live musicians in rehearsals, to know that I was going to be working in a different way with my movement director Imogen Knight to try and find a physical language. I knew that Rupert Goold wouldn’t want five people sat on chairs monologuing, and that was very releasing.

That’s a second artistic director you’ve mentioned after Dominic Dromgoole. I can’t think of two directors who are further apart in terms of what they put on the stage. Do you find yourself ever second-guessing what an artistic director might want out of you?

Um, I think you have an awareness of the audience that an artistic director might be trying to attract to that theatre. I was very conscious doing ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore that I’m in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse which usually is used for original practices and in a very traditional staging. I’m bringing my personality to certain expectations that a building or an audience might have. Rupert is always trying to surprise that and reinvent that and challenge that. It’s a licence. More than that, it’s a provocation to do that.

There will come a time soon when the general theatregoing public will come to see a play because it’s directed by Michael Longhurst. What would you say they can expect from a production of yours?

I hope what you get is a live experience where the design of the production is integral and challenging to the story being told. But I don’t know beyond that. I hope I tell stories about people that you care about and bring a bold theatricality to that. That’s my aim.

- A Number at the Young Vic until 15 August

- Constellations at Trafalgar Studios until 1 August

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

50 First Dates: The Musical, The Other Palace review - romcom turned musical

Date movie about repeating dates inspires date musical

50 First Dates: The Musical, The Other Palace review - romcom turned musical

Date movie about repeating dates inspires date musical

Bacchae, National Theatre review - cheeky, uneven version of Euripides' tragedy

Indhu Rubasingham's tenure gets off to a bold, comic start

Bacchae, National Theatre review - cheeky, uneven version of Euripides' tragedy

Indhu Rubasingham's tenure gets off to a bold, comic start

The Harder They Come, Stratford East review - still packs a punch, half a century on

Natey Jones and Madeline Charlemagne lead a perfectly realised adaptation of the seminal movie

The Harder They Come, Stratford East review - still packs a punch, half a century on

Natey Jones and Madeline Charlemagne lead a perfectly realised adaptation of the seminal movie

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

Romans: A Novel, Almeida Theatre review - a uniquely extraordinary work

Alice Birch’s wildly epic family drama is both mind-blowing and exasperating

Romans: A Novel, Almeida Theatre review - a uniquely extraordinary work

Alice Birch’s wildly epic family drama is both mind-blowing and exasperating

Add comment