Defining Beauty: The Body in Ancient Greek Art, British Museum | reviews, news & interviews

Defining Beauty: The Body in Ancient Greek Art, British Museum

Defining Beauty: The Body in Ancient Greek Art, British Museum

More than the sum of its parts: an exploration of how the human form was perfected

We think we know it when we see it. But how, pray, do we define beauty? The ancient Greeks thought they had the measure of it. In the 4th century BC, the “chief forms of beauty,” according to Aristotle, were “order, symmetry and clear delineation.” A century earlier, during the golden age of Athens, Polykleitos, one of the ancient world’s greatest sculptors, set out the precise ratios for the ideal male form in a treatise he called The Canon.

Neither Polykleitos’s Canon nor any of the great male nudes he created out of bronze, a material far stronger and more ductile than marble, have survived to the present day. In the ancient world, bronze figures were often melted down in times of war and used for weapon-making; or else they simply didn’t survive the iconoclasm of the early Christian era; or they were lost at sea during transportation, to be recovered some millennia later, just like the bearded and naked Riace Warriors were in the Seventies.

What we are left with are later Roman copies in marble, or in the case of the British Museum’s current exhibition, a 20th-century model of Polykleitos’s Doryphoros or “spear-bearer”. The reconstruction, by German sculptor George Römer in about 1920, looks remarkably kitsch in its smooth and unblemished state, though we may still admire its veiny-armed realism. Here it stands breast to breast with a Roman marble copy of Myron’s Diskobolos, or Discus Thrower, a work concerned with bodily perfection expressed through finely held balance and opposition. We see these oppositions, chiefly contraction and muscular relaxation, clearly in the form of the athlete in action. In less exaggerated form we also find it in Polykleitos’s deployment of contrapposto, in which one leg bears weight, while the other appears relaxed, and with the hip slightly off centre, suggesting either movement or at least a sense of vitality and presence.

The classical Greeks were experts in achieving such dynamic effects to heighten the realism of their figures. One very rare example of an original bronze nude is found here, and it is of an athlete just after a game. Dated to around 300 BC, it depicts an Apoxyomenos, a male figure-type representing an athlete, perhaps a wrestler, scraping a mixture of oil, sweat and dust from his upper thigh, his hand just hovering over his genitals, with a metal instrument called a strigil (though the implement is missing). The beautiful bronze figure (detail pictured below; Mali Lošinj, Croatia), boyish and youthfully plump of face, and with his head bowed and eyes alluringly cast down as if with an air of shyness and modesty, was recovered from the Adriatic sea off the coast of Croatia in the Nineties. The lips and nipples are inlaid with copper, the reddish tinge striking a note of sensuality and eroticism, making the figure feel even more keenly present.

But it’s not just idealised humans that Defining Bodies is concerned with, but a whole panoply of gods and goddesses, whom the Greeks also represented in perfected human form. All around are deities and half-deities from the Greek pantheon, as well as heroic mythological figures, such as Hercules enacting his 12 labours, found particularly in the decoration of drinking vessels and bowls. Although Aphrodite is the only female deity to be seen naked, it was usual to depict males – mortals, gods and demi-gods – unclothed, whether in repose or in battle. Unlike other ancient cultures, such as the Assyrian or Persian, nakedness among the Greeks is not associated with weakness or humiliation, but resolutely with moral virtue.

But it’s not just idealised humans that Defining Bodies is concerned with, but a whole panoply of gods and goddesses, whom the Greeks also represented in perfected human form. All around are deities and half-deities from the Greek pantheon, as well as heroic mythological figures, such as Hercules enacting his 12 labours, found particularly in the decoration of drinking vessels and bowls. Although Aphrodite is the only female deity to be seen naked, it was usual to depict males – mortals, gods and demi-gods – unclothed, whether in repose or in battle. Unlike other ancient cultures, such as the Assyrian or Persian, nakedness among the Greeks is not associated with weakness or humiliation, but resolutely with moral virtue.

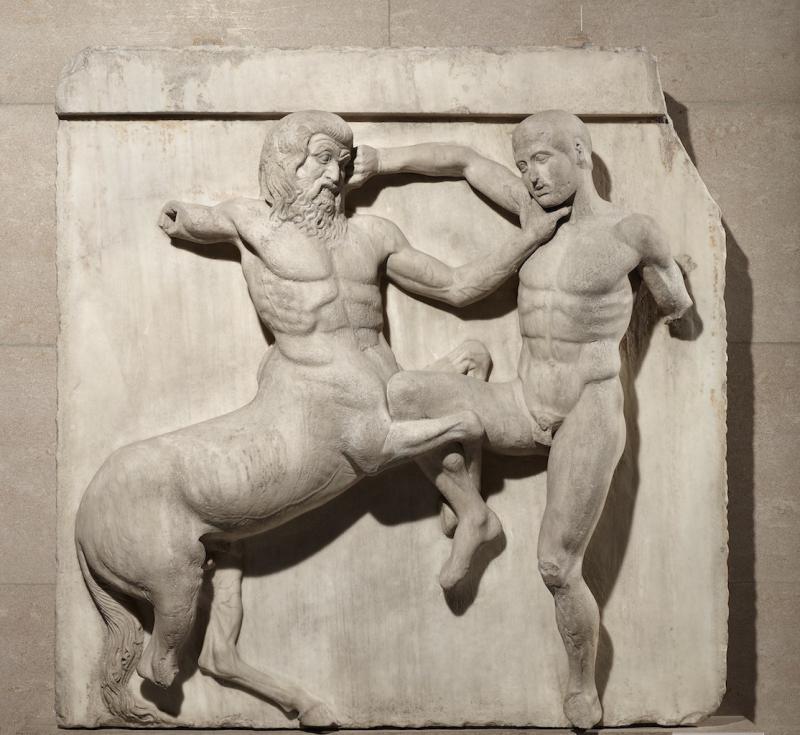

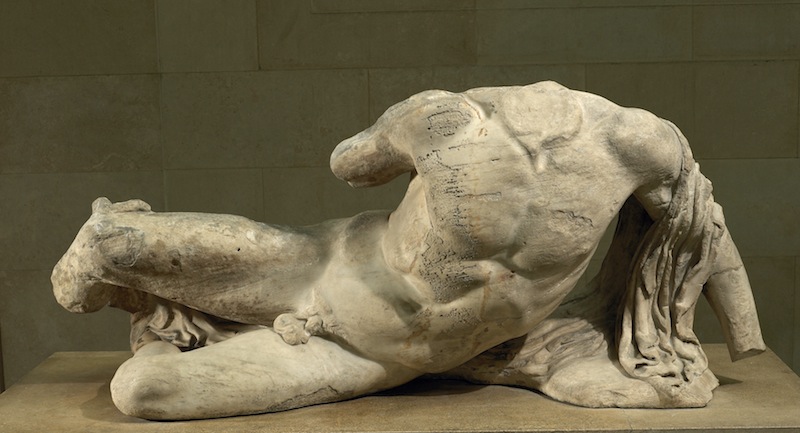

Defining Beauty is, as its title demands, a gorgeous as well as brilliantly illuminating exhibition, but it’s one with a clear message, made even more forcefully in the catalogue’s introduction, written by the museum’s director Neil MacGregor. In light of the ongoing controversy (given fresh impetus and urgency by Amal Clooney) as to where the Elgin Marbles (or, as we have been tutored to call them, the Parthenon Marbles) truly belong, this is an exhibition wanting to let us know, in no uncertain terms, that the British Museum is the best custodian of these ancient treasures. It is, of course, telling that of its many loans, not one is from a Greek museum. There is no hope of cultural rapprochement just yet, especially since, of course, we find a selection of the BM’s freestanding Parthenon sculptures, frieze fragments and metopes (see main picture), taking insouciant pride of place in the display, the splendid over-life-size river god Ilissos among them (pictured below; British Museum).

Pheidias, the other great sculptor of the 5th-century Athenian golden age, is the brains behind the art works of the Parthenon temple, an artist, we’re told, who had a more “intuitive” approach to the human figure. Certainly, the figures carved under his supervision seem to be more naturalistic and perhaps less schematic as exercises in balance and tension than Myron’s. But of course, and uniquely, these are originals – blasted, broken, weathered, with missing heads and limbs, but original all the same. And how much ruddier, ruder and alive they appear than the smooth Roman copies that replaced them.

Pheidias, the other great sculptor of the 5th-century Athenian golden age, is the brains behind the art works of the Parthenon temple, an artist, we’re told, who had a more “intuitive” approach to the human figure. Certainly, the figures carved under his supervision seem to be more naturalistic and perhaps less schematic as exercises in balance and tension than Myron’s. But of course, and uniquely, these are originals – blasted, broken, weathered, with missing heads and limbs, but original all the same. And how much ruddier, ruder and alive they appear than the smooth Roman copies that replaced them.

“Man is the measure of all things,” wrote the 5th-century BC pre-Socratic philosopher Protagoras. This humanist philosophy of the Classical Greeks certainly contributed to this great and unprecedented flourishing of naturalistic art. Just compare what came later with the thumb-sized bronze figure of Ajax (pictured left; 720-700 BC; British Museum), displayed in the gallery to which the title Giving Form to Thought has been given. It was made three centuries before the Parthenon sculptures, roughly around the same time as Homer was writing his epic poetry. This penile figure – wearing a crude helmet, its rudimentary body stick-like, suggesting, to me at any rate, a slightly curved penis – is depicted at the moment of extreme crisis. He is about to plunge a dagger into his abdomen. And, what do you know, we see that his actual, rather generously proportioned, penis is erect.

“Man is the measure of all things,” wrote the 5th-century BC pre-Socratic philosopher Protagoras. This humanist philosophy of the Classical Greeks certainly contributed to this great and unprecedented flourishing of naturalistic art. Just compare what came later with the thumb-sized bronze figure of Ajax (pictured left; 720-700 BC; British Museum), displayed in the gallery to which the title Giving Form to Thought has been given. It was made three centuries before the Parthenon sculptures, roughly around the same time as Homer was writing his epic poetry. This penile figure – wearing a crude helmet, its rudimentary body stick-like, suggesting, to me at any rate, a slightly curved penis – is depicted at the moment of extreme crisis. He is about to plunge a dagger into his abdomen. And, what do you know, we see that his actual, rather generously proportioned, penis is erect.

You'll not find much speculation here as to just why this roughly modelled figure has an erection, though it’s suggested that it might be to better express the trauma of the event. Who knows? Perhaps it’s because Ajax’s manliness is heightened by such an act of self-sacrifice. Or perhaps the anonymous artist was simply being roguishly playful. It has been known, for if anything lets us know how fully, rudely human the ancients were, this exhibition is it.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment