It is amazing how perceptions and attitudes change. Think of a nude and the chances are you will imagine a naked woman since, nowadays, the female body virtually monopolises the genre; naked men scarcely make an appearance in mainstream culture. This changed briefly in the 1970s, when American photographer Robert Mapplethorpe brought the male nude into focus with countless images celebrating masculine beauty. After his death in 1989, though, the naked male returned to the closet, relegated to porn movies and gay magazines.

In 17th and 18th century France, the reverse was true. The male physique was thought to embody perfection while the female form was considered an aberration. Study of the male nude was crucial for those anyone wanting to be an artist. The Paris art scene was dominated by the Ecole des Beaux-Arts where students underwent a rigorous formal training. The most ambitious hoped to become history painters with a remit that included Biblical and mythological scenes as well as heroic battles and key historic events. Key to this glorious enterprise was the mastery of life drawing which was central to the curriculum – so much so that figure studies became known as “académies”.

In 17th and 18th century France, the reverse was true. The male physique was thought to embody perfection while the female form was considered an aberration. Study of the male nude was crucial for those anyone wanting to be an artist. The Paris art scene was dominated by the Ecole des Beaux-Arts where students underwent a rigorous formal training. The most ambitious hoped to become history painters with a remit that included Biblical and mythological scenes as well as heroic battles and key historic events. Key to this glorious enterprise was the mastery of life drawing which was central to the curriculum – so much so that figure studies became known as “académies”.

Not only were female models barred from the life room on moral grounds, but so were female students. This convenient gambit excluded women artists from tackling grand themes that brought critical acclaim and relegated them to subjects considered minor, such as interiors and still lifes. Since it consists of male artists glorifying the male body, this exhibition of 37 life drawings borrowed from the Academy’s archive is, then, a very masculine and a very narcissistic affair.

Before they were allowed to draw actual models, students had first to hone their skills by copying drawings and engravings, and drawing casts of antique sculptures. And it shows; when it came to looking at real bodies, they viewed them through the lens of art history. In their drawings, living flesh acquires the dusty patina of a plaster cast or the smooth sheen of polished marble. In a process comparable to airbrushing a supermodel into a fashion icon, the imperfect bodies of mere mortals were given a rigorous makeover that transformed them into gods and heroes. A model holding a stick becomes Hercules clutching his staff (pictured above right); a youth on a cardboard box becomes Man Sat on a Rock, and a man lying on his back becomes a Falling Titan tumbling headlong through clouds, a look of abject terror on his face.

To help maintain difficult poses over many hours, the models often used props; posts, poles, ropes and boxes provided invaluable support for a raised leg or an arm held awkwardly aloft. In the drawings, conveniently placed drapery often hides the genitals, but other props are left out so that in Jean-Marc Nattier’s drawing of two men fighting, for instance, a hand holding onto a pole can become a fist ready to strike. Other props undergo a sea change into something richly evocative, such as a serpent, hammer or knife.

To help maintain difficult poses over many hours, the models often used props; posts, poles, ropes and boxes provided invaluable support for a raised leg or an arm held awkwardly aloft. In the drawings, conveniently placed drapery often hides the genitals, but other props are left out so that in Jean-Marc Nattier’s drawing of two men fighting, for instance, a hand holding onto a pole can become a fist ready to strike. Other props undergo a sea change into something richly evocative, such as a serpent, hammer or knife.

Dandré Bardon’s drawing (pictured above) reveals the process through which a reclining model is transformed into a dying warrior. The man lies prone on a heap of cushions and drapes. The fingers of one hand are looped through a chord attached to a post behind him, which enables him to keep one arm stretched above his head. Bardon places him on the diagonal in a position that reminds me of the dead Christ in Rubens’s painting The Descent from the Cross (1612-14), a reference that may have been intentional. The shield, helmet and spear tucked under the man’s right flank complete the heroic picture of a dying warrior.

To achieve the desired impression, others added imaginary props. Antoine-Jean Gros placed his man in a landscape beside a brazier; the bull lying at his feet already seems to have been killed by the stick-wielding hero. Antoine Paillet is even more ambitious; he poses his model in the position of Laocoön, the Trojan priest featured in an eponymous, first century Hellenistic sculpture, and entwines his limbs in serpent’s coils.

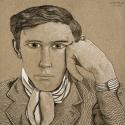

Carle Vanloo was one of the few who seemed able to respond directly to the model and draw what he saw. His red chalk study of a seated man, his arms crossed above his head (pictured left), is a tender portrait of a youth whose fine features would enable him to pass as a young woman. His pensive expression arouses real sympathy while, bathed in bright light, his slender body seems dreadfully vulnerable especially when compared with the surrounding brawn.

Carle Vanloo was one of the few who seemed able to respond directly to the model and draw what he saw. His red chalk study of a seated man, his arms crossed above his head (pictured left), is a tender portrait of a youth whose fine features would enable him to pass as a young woman. His pensive expression arouses real sympathy while, bathed in bright light, his slender body seems dreadfully vulnerable especially when compared with the surrounding brawn.

Many of these images would look at home in the pages of a gay magazine. With his perfect body and chiselled good looks, Jean-Baptiste Isabey’s Seated Man of 1789 (main picture) is especially delicious. Drawn in black chalk on brown paper, he appears to have a suntan while the white chalk highlighting his musculature gives the impression that his gleaming skin has been oiled all over. The idea invites one to caress his body with one’s eyes, if not one’s hands; it is hard to believe he was not equally seductive to 18th-century eyes.

- The Male Nude at the Wallace Collection until 19 January 2014

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment