theartsdesk Q&A: Soprano Anne Schwanewilms | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Soprano Anne Schwanewilms

theartsdesk Q&A: Soprano Anne Schwanewilms

The great Strauss interpreter on valuing stillness and why she chose to sing less Wagner

She is now the world’s leading interpreter of Richard Strauss’s Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier, the aristocratic thirtysomething once forced into marriage with a far from ideal husband and determined not to let it happen to the sweet girl who falls for her own much younger lover on first sight. As a happily married woman, Anne Schwanewilms has no need of 17-year-old boys, and in her vocal prime she can have no regrets about ageing beautifully, but she shares both the Marschallin’s wit, with a wicked line in impersonating certain conductors, and her natural charm.

Schwanewilms first beguiled the London public as the deserted heroine in an April 2000 concert performance of Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos at the Barbican, with Simon Rattle conducting the London Symphony Orchestra, and she’ll be there with the same orchestra under Mark Elder on Thursday in excerpts from Der Rosenkavalier: two other perfect interpreters, Sarah Connolly and Lucy Crowe, will join her as, respectively, lover Octavian and Sophie, the girl with whom he falls instantly in love as bearer of a rose from an unattractive, boorish suitor. This is truly Rosenkavalier month, just before the composer’s 150th birthday: Glyndebourne opens with the opera the following week, and then there’s a concert performance in Birmingham conducted by Andris Nelsons on the 24th.

Though the UK has yet to see Schwanewilms’s Marschallin on stage, I was lucky enough to catch her in Dresden last June in an evening of rare perfection – albeit without sets, which couldn’t be transported, owing to the floods – and I spoke to her in London just before the latest of her hugely successful Wigmore Hall Lieder recitals.

Though the UK has yet to see Schwanewilms’s Marschallin on stage, I was lucky enough to catch her in Dresden last June in an evening of rare perfection – albeit without sets, which couldn’t be transported, owing to the floods – and I spoke to her in London just before the latest of her hugely successful Wigmore Hall Lieder recitals.

DAVID NICE: So as this is the big anniversary year, can we talk mostly about Strauss? I first saw you as Ariadne at the Barbican – were you just making your name then?

ANNE SCHWANEWILMS (pictured right by Javier de Real): It was a big, huge success in England, though I hadn’t got the impression that it was a big breakthrough. That for me was when I first sang the Marschallin in Chicago in 2006. The problem for me was that I started as a mezzo and in 1996 I changed my fach [vocal type] to soprano because of being told, because my name is Schwanewilms [the swan, I suppose, key in Lohengrin and Parsifal], they thought I had the qualities to be a Wagnerian soprano, which I hadn’t ruled out completely, but I doubted that I would sing only Wagner. In 2002 I sang Senta, Sieglinde and Beethoven’s Leonore, and I had eight contracts lined up until 2005, only Brünnhilde, Elektra, Salome and the Beethoven. I asked my agent, are they asking me for any other repertoire, is there any chance to get a foot in the door with Strauss, with the Marschallin?

At first I was very pleased that they heard the potential, and after the third time, I thought, there’s something wrong, I think I speak a different language, and how can I stop, so I stopped it, and said no to all eight signed contracts. My agent was shocked, but he did it. And rumours went around, she can’t sing, she’s finished. But after a short time with the help of my agency, they accepted it. But opera is a lazy planning world, they react not directly, they will offer you in two or three years an engagement, I’m planning now my years in 2017, and 18, the years before are full. Anyway, in 2002 I cancelled the contracts, and four years later I was offered my first Marschallin in Chicago. And this was for me the coming out, the Marschallin, the Strauss roles, and I realized that I was right, but I needed time to understand their language…

People are so eager to fill the Wagner slots, and singers get used up in that way.

People are so eager to fill the Wagner slots, and singers get used up in that way.

And I could have filled my whole calendar up like that for years (left, Schwanewilms as Elsa in Lohengrin, photo by Mario Brescia). But I wanted to give my voice space to develop with less pressure – I already have enough pressure, with travelling, organizing, learning. When I look back I see I did the right thing, but at the time I felt punished, guilty, because I denied contracts I had signed for a reason I wasn’t sure at the time was right or wrong.

So it was a big risk for you.

It was a big risk, yes, but in 2006 I knew, ah, I am a Strauss soprano. Then I was surprised - at that moment I thought, couldn’t they hear a little bit further?, but this is not their job. You as a practical person offer them the possibilities and they make the decision. Instantly I thought I am right for Strauss, of course, but I hadn’t known how good I could be.

Thinking back to Chicago, how did you feel on stage that made you feel different from having sung the bigger, more dramatic roles, psychologically?

[Lilting sing-song voice] Easy-going, flowing soprano, nothing to do, only enjoying the world of a singer.

Because there’s the line about the Marschallin having one eye wet, the other dry, and some sopranos are too tragic. But you seem to have so much fun with the role.

I do.

Every time?

Every time, there’s no doubt – nobody can destroy that, they can only support my fun.

So even if there’s a director who has a concept with which you don’t agree?

There’s no doubt, I have fun. This is a good basis for being sure of oneself, and you can fill the whole stage by doing virtually nothing. And this is what I want to reach, I don’t want to do a lot with my voice, it's something which needs space, time and shows me how to react, and I have to take care of it, to be responsible for it, but the voice is doing what the voice is doing and likes to do, so I’m looking sometimes like a visitor from above and hearing, with help from my teacher too, and asking, is it flexible still enough? Does it like these roles? There’s a big responsibility.

So it’s a mixture of intuition and responsibility?

Intuition I can show onstage, but the main work is behind the stage, behind doors where you are looking on it. I’m careful enough, can I give enough space for the voice, can I support it? Mostly you are doing too much.

So you’re talking about not just the voice, this stillness which has always been such a quality with you, and you seem very relaxed, physically. Quite a few singers seem tense, or move around too much.

Well, the Marschallin [pictured right by Claus Gigga for Dresden's Semperoper with Elina Garanča as Octavian] helps me a lot to be relaxed. But the main thing is that when you are playing an instrument, an instrument is every time as good as the circumstances around, the temperature, the humidity, the player, softly playing. The instrument has to be known - where do I push or give the instrument a potential to show where the potential is.

Well, the Marschallin [pictured right by Claus Gigga for Dresden's Semperoper with Elina Garanča as Octavian] helps me a lot to be relaxed. But the main thing is that when you are playing an instrument, an instrument is every time as good as the circumstances around, the temperature, the humidity, the player, softly playing. The instrument has to be known - where do I push or give the instrument a potential to show where the potential is.

Weren’t you a string player?

No, I was a guitarist. When I was 15 I wanted to play classical guitar, and it was the only possibility for my parents to pay for the lessons, because they had not enough money, piano lessons were more expensive and we had no piano, so my grandma bought a cheap guitar, a cheaper version. But I was happy to learn something, I wanted to make music.

But I interrupted – you were talking about the voice as instrument?

In my opinion we always forget that voices are similar to instruments, and the main difference is that with an instrument you can see from outside in which shape it is, what condition, from outside. For a singer where are the conditions? The vocal cords are two centimetres long, so what kind of conditions make a singer successful, the cords around, the body, language, intelligence? Most of the time you are talking to yourself as a psychological person, there are psychological reasons, you want more, and the vocal cords have to show strength all the time. An instrument where the strings are too strong, too tightly tuned, you can hear it. So I can’t change my cords. They are where they are, the quality is how they are, but the body is the instrument around, I can support the circumstances for these two cords. There’s a lot of potential, sometimes you can manipulate and sometimes you shouldn’t.

And this is all a kind of taste. Some teachers say, of course, you have to do this and that. I’m still working until I’m not a singer, is this the right decision or not? It’s a very interesting discussion always, and even harder to make a discussion on your own. I need always people around me who know me, my voice, and whom I can trust, my husband, trainer, coach, teacher, who give me a response, and my instinct is always to give space. Then I feel always a peace in myself and it can’t be wrong. In a Lieder recital it can’t be wrong when I feel space, freedom, you hear your notes flowing. You hear it sometimes when Lieder singers go for tough notes and it’s too strenuous and tight When I see that, I know there can’t be a relaxation in the cords. It should be a no-activity thing in your body – how can you support it in song? You should do nearly nothing [whistles], then you get space in the front for the public, they can see it in your face and they can hear it, because the voice is doing nearly nothing. You can train it, I’m training to do that…

As your recent recitals have borne out. (Below, Schwanewilms sings Strauss's "Wiegenlied"in Barcelona.)

I hope so. And this is one reason why I need these recitals to show me because nowadays all is activity, colours and loudness, all bustle, I haven’t got this opinion. Music is sometimes enough, and our civilization is always too loud, too much, we are losing the silence, the quality of doing nothing, of enjoying by doing nothing [laughs]

With a psychological activity to support it, or am I wrong?

No that’s the right word, psy-cho-logical [laughs].

Do you meditate?

No, not really, but I do a lot of Alexander Technique, for me it’s a form of meditation, because I calm down with the body, it tells me what condition I am, and sometimes it’s not nice [laughs].

That being your instrument, It must be difficult in the continental repertoire system – for that Rosenkavalier in Dresden, I understood you had only one orchestral rehearsal.

That being your instrument, It must be difficult in the continental repertoire system – for that Rosenkavalier in Dresden, I understood you had only one orchestral rehearsal.

It was a short rehearsal time with [conductor Christian] Thielemann. [Schwanewilms' Marschallin in that production pictured left]. Sometimes these are not the ideal circumstances to show the best quality in the relationship, it needs time of course, but this is also life. Thielemann doesn’t like to rehearse often, he’s very intense. I like it in a way but the main thing is then that I have to follow him, there’s no discussion, no communication, no asking, what do you like? But at that time I was surprised, I didn’t realize it to begin with, I realized it after the first performance, we did a general rehearsal. I realized at the premiere that he is a genius, a special conductor, he must have a phenomenal brain. He knew what I liked to support, and I couldn’t have known that in the rehearsal, he prepared the orchestra, one or two bars before, to prepare my line which he likes to support, and I was really touched by that because then I realized he is the one who remembers, he prepared the colours for my colour.

I have never met a person who reacts so quickly, and this means he is so tense, I couldn’t stand that [vivid impersonation follows]. But he is concentrating and is always thinking ahead. Rosenkavalier is a long opera, and it must exhaust him. But it’s a masterclass of brainwork. This is the reason why he is Mr Thielemann, why he’s so famous. He doesn’t talk a lot. And always... [the impersonation of fierce tension again]. But he is concentrated, how can he get this colour out of the orchestra. I find that really amazing.

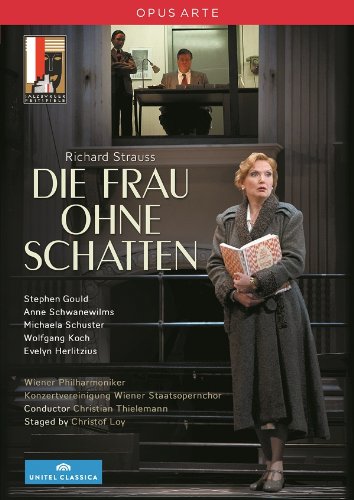

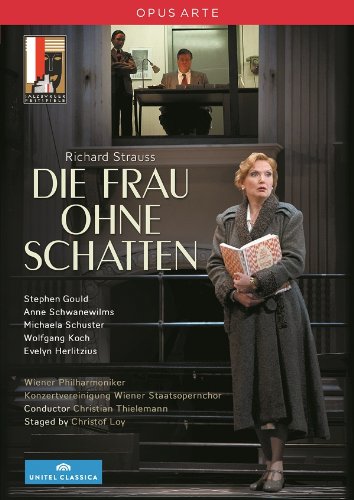

You’d worked with him in Salzburg, on Christof Loy’s new production of Die Frau ohne Schatten. There must have been more long-term preparation there.

You’d worked with him in Salzburg, on Christof Loy’s new production of Die Frau ohne Schatten. There must have been more long-term preparation there.

And the Empress was a new role for me, I wasn’t always sure when I was studying the role, but I knew in parts what line I would like to take. So I’m not loudly insisting, but constantly insisting, please could you hear this, I would like to make a little rubato here. Some conductors are very sensitive and some not, and in his eyes I saw, no, yes, yes, mmm, maybe. So I was very clear after the first rehearsal that I could try some things again, he likes it, that he doesn’t like so much, so I can follow him to see what he wants to support. So it’s easy work in a way but also I have to concentrate so hard psychologically, to communicate without words [more impersonation]. But this is not completely right. This is what we understand immediately, but you see in his eyes, the orchestra is panting with fear, and as a singer you are much further away, you can’t lose him or you’re in trouble. What he doesn’t like he doesn’t show directly, but you feel it.

That must have been a strange process, partly because Loy had a vision of the fairytale opera as a 1950s recording-studio event, which none of us thought could work, and yet it mostly did, and that was your first acquiaintance with a very strange role.

I was already engaged for his idea, from the first day on, I know Christof and for me it was a clear language, he couldn’t deal with that fairytale story, he didn’t like it, so what shall we do? Nothing. We should follow him from the beginning on, and if I didn’t understand quickly what he wanted to support, I should have left. But I did understand, and I thought it’s a very good idea, for me it’s the best if you can’t deal with the fairytale.

I was in New York at the Met last November, in an old Wernicke production from 2002, he didn’t interpret a thing. I never met him – two months after that production he died, but he was a painter of wood and stone, he wasn’t a stage director, he didn’t describe why you should walk from that point to that point, there was no explanation, and I was completely free, and I loved that. But you as an actor, you are more responsible, and some can take it and some can’t. They are standing or walking and you think is there a reason? No, then you are not interested in the person. Wernicke was a light fantast, he was a colour fantast, he saw always pictures and dramas through lighting, brilliant, beautifully done. I couldn’t imagine how beautiful this piece could be on stage by telling only the story. One picture after another, nothing else.

But this was Wernicke. The stage was divided up, I was in one part and I could hardly see the conductor, and Vladimir [Jurowski] told me, this is the first time that I couldn’t see the singer… But the effect for the audience was breathtaking. I was put in a mirror box with a steep rake (pictured left). Very dangerous. I slipped twice and I had to go to hospital, but I was burning for it because in this mirror box every mirror was giving a different perspective, and in the audience the light was broken differently, everywhere stars, and I wanted to move like a bird with less weight. It worked, but I had to rehearse in this mirror box. For me, because it’s hard to sing this role and then with a lightness and ease of movement, I had to rehearse it. And even if it didn’t work immediately, I had to find the calm to do it again. This was really something. And I burned for it just as two years earlier I had burned for Christof’s idea, and I understood them both.

But this was Wernicke. The stage was divided up, I was in one part and I could hardly see the conductor, and Vladimir [Jurowski] told me, this is the first time that I couldn’t see the singer… But the effect for the audience was breathtaking. I was put in a mirror box with a steep rake (pictured left). Very dangerous. I slipped twice and I had to go to hospital, but I was burning for it because in this mirror box every mirror was giving a different perspective, and in the audience the light was broken differently, everywhere stars, and I wanted to move like a bird with less weight. It worked, but I had to rehearse in this mirror box. For me, because it’s hard to sing this role and then with a lightness and ease of movement, I had to rehearse it. And even if it didn’t work immediately, I had to find the calm to do it again. This was really something. And I burned for it just as two years earlier I had burned for Christof’s idea, and I understood them both.

And with Loy you were very much the centre of the opera, whereas the Empress can seem to disappear for long stretches.

That was his idea. I knew friends and colleagues in the audience who didn’t understand it, and at first I thought I wasn’t good enough because I couldn’t explain it through my body, but after a short time I found other people who did understand it.

It has the potential to be a complicated story. I don’t think it is.

I don’t think so either. But if you don’t think it’s complicated, you follow the fairy story scene by scene, and make no explanation and no interpretation. This is not Christof’s work, he’s always interpreting, and I accept this always when there is a logical answer for it. Then I can go for it, and I should find a way to show this opinion, but for me it was very good to see that this story works when you don’t interpret anything. In the end always a production is a question of how is the stage director working, is he or she an active force who wants to influence or not? Sometimes it’s working, and as an audience you have to accept it, or you don’t accept it and it doesn’t work. This is art. But the director also has to trust the music and not doubt too much. There are lot of doubters around us, a production from someone like that can offer many touching moments, but sometimes you think, this is too much, we lost the main thing, the music, I want to hear more music, and this is where I come back to space, quietness supports always space, or is supported by giving space.

That struck me with the Marschallin’s monologue. Dresden is a large house and I was sitting some distance from the stage, but I still felt drawn in by your quietness, I got that feeling that you were singing to me individually. I guess having a native singer who completely understands the text helps.

But it’s my way to sing and the Marschallin helps my capital. Usually it’s in recital that I can show most facets, I can show the subtext more by covering the voice, by setting the voice without vibrato. The Marschallin is talking, there are more recitatives than you think though Strauss sets none in form, this is parlando, a spoken style. I can support it with my technique, with my colours, like a painter, Strauss’s music sets Hofmannsthal’s text perfectly for these features.

Then there are the long lines, like the one which launches the trio, “Hab mir’s gelobt".

The soaring long line, I like it. This is the reason why I’m a Strauss soprano, and not a Wagnerian soprano, because a Wagnerian voice has more capital features in the middle range, in the dynamic potential, and I have limits there. I could sing more with the chest voice higher, but there would be consequences for my top, I don’t want that yet.

Is that why so many Wagnerian sopranos lose the body and the pitch at the top?

This is the reason, because when you start to put too much chest voice into the top, the result is that your high notes are getting narrowed, smaller, and sharper, which means lower pitch, it’s always too low, because your head voice is more going away. It’s unbalanced, and I know my voice needs time, doesn’t want to be pushed, so I have to take responsibility for that.

So is Sieglinde as far as you would go now?

I do like to sing it, I would like to sing it again, but in 2017-18, and Fidelio again, because everyone now expects that I’m a Strauss soprano and no-one expects that I will push my voice in the middle range. If a conductor or a house engages me they know what they get. So I haven’t pushed. I offered my proper potential and it has been accepted in the world. This is all right, I love singing Marschallin, Ariadne, Arabella (pictured right, above, by Monika Rittershaus with her "Mr Right"), Chrysothemis, Danae.

I do like to sing it, I would like to sing it again, but in 2017-18, and Fidelio again, because everyone now expects that I’m a Strauss soprano and no-one expects that I will push my voice in the middle range. If a conductor or a house engages me they know what they get. So I haven’t pushed. I offered my proper potential and it has been accepted in the world. This is all right, I love singing Marschallin, Ariadne, Arabella (pictured right, above, by Monika Rittershaus with her "Mr Right"), Chrysothemis, Danae.

Die Liebe der Danae is such a gorgeous, moving opera, and it’s a shame we’ve not had it in Britain this Strauss anniversary year.

It’s glorious, but It’s hard to find the cast. The bass-baritone for Jupiter is really hard to find, the voice range is high for a baritone. There’s a singer in Dresden, Hans Joachim Ketelsen. He was a house baritone in East Germany and was always asked if he wanted to jump into the tenor fach, and he denied always. But this was a good decision, because later he gave his voice time, so that the deep developed on its own and he could keep his high notes as a baritone. For that baritone it’s a brilliant role. Franz Grundheber has the high notes but not the deep ones, but he is a very good actor, so when he couldn’t support the deep notes you get something different – stage presence, so you didn’t miss anything.

Bryn Terfel might sing it.

It’s too high for him, I think. The deep notes are no problem for him, mmm, wonderful. But Strauss offered some possibilities to change the high notes. I have a picture of Strauss sitting on his bench with the score of Die Liebe der Danae, this typical score, wide frame and red and yellow colour for the letters, studying… This was the second last opera.

He thought it would be his last. Capriccio was an afterthought. Have you sung the Countess?

Not live. I would like to, but it’s rarely done. Once I was offered it and I couldn’t because I was already engaged.

There was a very beautiful production at Glyndebourne, set in the 1920s, the Strauss family didn’t like that so it was never filmed. Elisabeth Söderström sang it and then Felicity Lott.

[Wistful] Felicity Lott – a brilliant singer, very intelligent and a nice, nice, nice person. And she is English, you see, and yet she understands the German. There shouldn’t be a reason for a singer to show the public, oh I’m a foreigner. Sorry, it’s your activity or non-activity to say I understand this role. In Italy to sing Italian as a foreigner is not accepted. If there is any pronunciation not completely as they want to hear it, they are very rude. I didn’t experience this personally but I saw it in faces when I thought, the singer is making a brilliant Italian sound, so why are they complaining? But they complained loudly and very rudely, I didn’t like that. English people are different, they are always happy when you speak in English that they are not forced to talk in a different language, I love England for that.

You’ve sung at the Wigmore quite a bit. (Schwanewilms pictured left backstage with pianist Roger Vignoles after a recital last year.)

You’ve sung at the Wigmore quite a bit. (Schwanewilms pictured left backstage with pianist Roger Vignoles after a recital last year.)

Eight or nine times.

It’s a good space for you?

Boris Becker first went to Wimbledon when he was very young. And always in Germany he said this is my Wohnzimmer, my living room. And I say now, my Wigmore is my Wohnzimmer, I love it.

When you have a loyal public, the same people will come every time.

And they are the most educated public in the whole world. In Amsterdam you have a similar audience. You look and see some of them know every line, it’s unbelievable. I like it because I can risk a lot of subjective things which are not written officially in the score, but they understand it because they understand what the text is about, so they react directly, sometimes – I like that very much, I do like to get reactions.

Your Wagner Wesendonck Lieder was stunningly different, because it was so unforced, but then when you got the strong stuff, it was amazing, and people said in the interval, oh I never heard it sung like that. It can be too stentorian, but this was very lyrical and intelligent.

It should be. Because Wagner is very clear what he liked to support. He was the only one engaged to build up his own opera house. Why? He knew that he wanted a big huge sound but only the potential of it, 12, 14 violins, but in Bayreuth you can get a perfect pianissimo from such forces. I sang the Four Last Songs in Manchester with Markus Stenz in February. This orchestra [the Hallé] is typical for an English orchestra, is able to play piano. You start [she sings the opening lines] and think, oh, thank you, even in lower parts I hadn’t to push, never. Before and after I sang them somewhere else, but I promise, it was so loud. When you see the orchestral score, there are a lot of places when you think, if Strauss had lived to hear them he would have altered some of the dynamics. But the Hallé play with one single voice. As a conductor you take over the responsibility for that, but most conductors don’t take enough time for that. It takes time, to say, uh-oh, you hear, don’t follow him - I show you the sort of dynamic you should play, don’t follow your partner, trust me, look at me.

I t’s a question of building a relationship, like Mark Elder has in Manchester and Markus Stenz in Cologne.

t’s a question of building a relationship, like Mark Elder has in Manchester and Markus Stenz in Cologne.

The Hallé isn’t Markus’s orchestra, but they were really playing like Mark’s group. Lovely. And Wagner had the same idea. In several books you can read his idea about the singer’s relationship to the orchestra. It’s always the main idea that a singer must be heard, and the silence is the main thing which I want to offer. When you hear – [she sings the Valkyrie theme] – where’s the silence there? But there’s a misunderstanding.

The Wesendonck Lieder with piano are completely different, but you hear it in the score and read it. The main difference is the orchestra has the potential to play loud but to build up this atmosphere of pianissimo, or vibrato or echo but it doesn’t come into the front, it’s a holding back situation, and when it does come forward it’s overwhelming. With the original Wesendonck Lieder, there’s more a conversation between the singer and the piano, not an image of the orchestra colours. This means the singer should search for different colours. Then you realize you can support more the consonants, and make sense with this alliteration, which he loved so much.

Some Strauss Lieder were composed with orchestra and some were orchestrated later. You sing them in both versions - do you find cases where one works better than another?

Of course, and you hear the difference when someone else made the orchestration. Also Strauss is such a genius in setting words in music. In the operas, with Hofmannsthal there was a celebration of a relationship in word, text and music. Wagner composed his own words and line and you hear it. I hear immediately what Wagner wanted, but after a while there was no wedding with different influences. He wasn’t influenced much and so there was not a big development in his life. Strauss lost Hofmannsthal and went in different directions, but he still composed Die Liebe der Danae on an old suggestion of Hofmannsthal. He was looking back in the 1940s, he carried on living in Germany when the political system had been killed by the Nazis, he felt unjustifiably punished because he thought he’d done the right things, he helped Jewish people in his opinion, and other people punished him because he didn’t stand up in Germany and fight against the Nazis.

He was an old man by then.

And he hadn’t got this character – it was always music, music, and he didn’t take the Nazis seriously at first, he thought like a lot of people thought, they are really stupid, and he took the chance to be paid and do his job and had nothing to do with politics. It was a wrong thing to do. But when you’re looking back, you know every time what’s better. So Strauss was missing a lot and he filled it with this composition Liebe der Danae. I understand what his psychological situation was.

He’s a difficult person to read, there often seems such a gulf between the man and the work.

For me, it’s a typical English situation, English people learn how to hide themselves behind an image, sometimes very nice and easy to talk to someone, because they are always very friendly. I like that very much, but when you want to come a little bit closer, you realize, oh, there is not a chance to go further. Strauss was a person like that, and his wife Pauline was at that time very ill and he was pushed already into a retrospective situation, older times were better.

He immersed himself in Mozart and Goethe.

Older times, classical times, culture destroyed. How dare they do that? But that was his psychological situation, hiding himself more than before in a very Prussian way.

Though he was Munich-born, wasn’t he?

But he learned that and built up the façade more and more to hide himself and his unsureness – he was very disciplined, 9 to 12 composing, then from 2 to 5 and in between he was walking or eating or sleeping but it was a disciplined day. He was in control and Pauline was the opposite.

You have a wonderful talent for comedy. What about Intermezzo [a thinly veiled dramatization of an upheaval in the Strausses’ married life]?

It should be there. Capriccio, Intermezzo, these are big wishes on my top list. Please, responsible people, give me the chance to sing those, give me the time, and put them quite early in my calendar.

Would you go back to Glyndebourne [where she sang Weber's Euryanthe]? There’s good preparation there. Vladimir Jurowski was always around from the first rehearsal, and now Robin Ticciati is too.

Would you go back to Glyndebourne [where she sang Weber's Euryanthe]? There’s good preparation there. Vladimir Jurowski was always around from the first rehearsal, and now Robin Ticciati is too.

For Capriccio that would be perfect. Intermezzo I looked into, there are several scenes I liked, but there is no red line through. Capriccio I did so it is easy for me, perfect for Glyndebourne. Intermezzo, I’m not sure yet.

Christine [the Pauline character] needs real charm. Too often she can be seen as a termagant, a nightmare person.

No, I’m sure she isn’t, she can come across that way. It’s because of insecurity - she is a more introvert person than her husband, she reacts in a different way to hide herself, to seem extrovert. The Marschallin or Capriccio Countess must never be extrovert, you use very small gestures and it fills the room. In Intermezzo the main interest for me is that there's always a reason for a big reaction, a tantrum, two pages before it happens, or one line before, and it should be not loud but directly seen why the change is so huge or why she’s bad. She is very, very intelligent but not well treated, so to show the history of the character is important. [Janáček’s The] Makropoulos [Case] is sometimes similar.

Have you sung the role of Emilia Marty?

I would like to, but this is a completely different role, bright middle range. But if a conductor wants me… I was asked in the past, 30 times, Salome and Makropoulos. Salome I will never sing because the orchestra is too big, it’s not really a chance to show the intimacy, he wasn’t interested in that, I have no chance then. With Chrysothemis [in Elektra, pictured above by Clive Barda in the Royal Opera production], there are tiny indications of intimacy – like when she sings "der Vater der ist tot", this is a reason for me to sing a role, Salome is always extrovert, exhibitionism, I’m not the right type. But in Makropoulos, there are a lot of chances – I would like to do that. At that time it was the same reason, the big middle range, oh no, stop it, it’s too early - but now 2017, 18, 19, let’s see.

One big question – could you, would you, sing Isolde?

I’m not sure. “Mild und leise” [the so-called Liebestod] is on the new Wagner CD. I would like to study the whole role but I must try it out first in a concert, to see how I feel, because there are some intimate parts which interest me, there are somehow places - in a room with a piano I can sing it, but on stage the question is how can I keep my voice clear enough for the intimate places.

Margaret Price recorded it, memorably, for Carlos Kleiber, and never sang the role on stage..

I heard that once years ago, and this is my idea of an Isolde. For me many factors come into play: I need a staging that’s intimate, not expressionistic, and a conductor who’s interested in keeping the orchestra down. Then I will say yes. If it doesn’t come, then I will deny it. My quality is obviously more in the silence than in the loudness. Trust me, trust the music and the line. Perhaps I’ll never sing Isolde in my life, but this is my taking care of myself. If I feel free then there’s a result, people will understand why I want to sing that kind of role, otherwise they won’t. I always want to feel comfortable on stage.

- Anne Schwanewilms sings the Marschallin in excerpts from Der Rosenkavalier at the Barbican on Thursday

- David Nice's blog on the June 2013 Dresden Rosenkavalier

Overleaf: watch the trailer for Anne Schwanewilms's new Wagner recording, beginning with "Träume" from the Wesendonck Lieder

She is now the world’s leading interpreter of Richard Strauss’s Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier, the aristocratic thirtysomething once forced into marriage with a far from ideal husband and determined not to let it happen to the sweet girl who falls for her own much younger lover on first sight. As a happily married woman, Anne Schwanewilms has no need of 17-year-old boys, and in her vocal prime she can have no regrets about ageing beautifully, but she shares both the Marschallin’s wit, with a wicked line in impersonating certain conductors, and her natural charm.

Schwanewilms first beguiled the London public as the deserted heroine in an April 2000 concert performance of Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos at the Barbican, with Simon Rattle conducting the London Symphony Orchestra, and she’ll be there with the same orchestra under Mark Elder on Thursday in excerpts from Der Rosenkavalier: two other perfect interpreters, Sarah Connolly and Lucy Crowe, will join her as, respectively, lover Octavian and Sophie, the girl with whom he falls instantly in love as bearer of a rose from an unattractive, boorish suitor. This is truly Rosenkavalier month, just before the composer’s 150th birthday: Glyndebourne opens with the opera the following week, and then there’s a concert performance in Birmingham conducted by Andris Nelsons on the 24th.

Though the UK has yet to see Schwanewilms’s Marschallin on stage, I was lucky enough to catch her in Dresden last June in an evening of rare perfection – albeit without sets, which couldn’t be transported, owing to the floods – and I spoke to her in London just before the latest of her hugely successful Wigmore Hall Lieder recitals.

Though the UK has yet to see Schwanewilms’s Marschallin on stage, I was lucky enough to catch her in Dresden last June in an evening of rare perfection – albeit without sets, which couldn’t be transported, owing to the floods – and I spoke to her in London just before the latest of her hugely successful Wigmore Hall Lieder recitals.

DAVID NICE: So as this is the big anniversary year, can we talk mostly about Strauss? I first saw you as Ariadne at the Barbican – were you just making your name then?

ANNE SCHWANEWILMS (pictured right by Javier de Real): It was a big, huge success in England, though I hadn’t got the impression that it was a big breakthrough. That for me was when I first sang the Marschallin in Chicago in 2006. The problem for me was that I started as a mezzo and in 1996 I changed my fach [vocal type] to soprano because of being told, because my name is Schwanewilms [the swan, I suppose, key in Lohengrin and Parsifal], they thought I had the qualities to be a Wagnerian soprano, which I hadn’t ruled out completely, but I doubted that I would sing only Wagner. In 2002 I sang Senta, Sieglinde and Beethoven’s Leonore, and I had eight contracts lined up until 2005, only Brünnhilde, Elektra, Salome and the Beethoven. I asked my agent, are they asking me for any other repertoire, is there any chance to get a foot in the door with Strauss, with the Marschallin?

At first I was very pleased that they heard the potential, and after the third time, I thought, there’s something wrong, I think I speak a different language, and how can I stop, so I stopped it, and said no to all eight signed contracts. My agent was shocked, but he did it. And rumours went around, she can’t sing, she’s finished. But after a short time with the help of my agency, they accepted it. But opera is a lazy planning world, they react not directly, they will offer you in two or three years an engagement, I’m planning now my years in 2017, and 18, the years before are full. Anyway, in 2002 I cancelled the contracts, and four years later I was offered my first Marschallin in Chicago. And this was for me the coming out, the Marschallin, the Strauss roles, and I realized that I was right, but I needed time to understand their language…

People are so eager to fill the Wagner slots, and singers get used up in that way.

People are so eager to fill the Wagner slots, and singers get used up in that way.

And I could have filled my whole calendar up like that for years (left, Schwanewilms as Elsa in Lohengrin, photo by Mario Brescia). But I wanted to give my voice space to develop with less pressure – I already have enough pressure, with travelling, organizing, learning. When I look back I see I did the right thing, but at the time I felt punished, guilty, because I denied contracts I had signed for a reason I wasn’t sure at the time was right or wrong.

So it was a big risk for you.

It was a big risk, yes, but in 2006 I knew, ah, I am a Strauss soprano. Then I was surprised - at that moment I thought, couldn’t they hear a little bit further?, but this is not their job. You as a practical person offer them the possibilities and they make the decision. Instantly I thought I am right for Strauss, of course, but I hadn’t known how good I could be.

Thinking back to Chicago, how did you feel on stage that made you feel different from having sung the bigger, more dramatic roles, psychologically?

[Lilting sing-song voice] Easy-going, flowing soprano, nothing to do, only enjoying the world of a singer.

Because there’s the line about the Marschallin having one eye wet, the other dry, and some sopranos are too tragic. But you seem to have so much fun with the role.

I do.

Every time?

Every time, there’s no doubt – nobody can destroy that, they can only support my fun.

So even if there’s a director who has a concept with which you don’t agree?

There’s no doubt, I have fun. This is a good basis for being sure of oneself, and you can fill the whole stage by doing virtually nothing. And this is what I want to reach, I don’t want to do a lot with my voice, it's something which needs space, time and shows me how to react, and I have to take care of it, to be responsible for it, but the voice is doing what the voice is doing and likes to do, so I’m looking sometimes like a visitor from above and hearing, with help from my teacher too, and asking, is it flexible still enough? Does it like these roles? There’s a big responsibility.

So it’s a mixture of intuition and responsibility?

Intuition I can show onstage, but the main work is behind the stage, behind doors where you are looking on it. I’m careful enough, can I give enough space for the voice, can I support it? Mostly you are doing too much.

So you’re talking about not just the voice, this stillness which has always been such a quality with you, and you seem very relaxed, physically. Quite a few singers seem tense, or move around too much.

Well, the Marschallin [pictured right by Claus Gigga for Dresden's Semperoper with Elina Garanča as Octavian] helps me a lot to be relaxed. But the main thing is that when you are playing an instrument, an instrument is every time as good as the circumstances around, the temperature, the humidity, the player, softly playing. The instrument has to be known - where do I push or give the instrument a potential to show where the potential is.

Well, the Marschallin [pictured right by Claus Gigga for Dresden's Semperoper with Elina Garanča as Octavian] helps me a lot to be relaxed. But the main thing is that when you are playing an instrument, an instrument is every time as good as the circumstances around, the temperature, the humidity, the player, softly playing. The instrument has to be known - where do I push or give the instrument a potential to show where the potential is.

Weren’t you a string player?

No, I was a guitarist. When I was 15 I wanted to play classical guitar, and it was the only possibility for my parents to pay for the lessons, because they had not enough money, piano lessons were more expensive and we had no piano, so my grandma bought a cheap guitar, a cheaper version. But I was happy to learn something, I wanted to make music.

But I interrupted – you were talking about the voice as instrument?

In my opinion we always forget that voices are similar to instruments, and the main difference is that with an instrument you can see from outside in which shape it is, what condition, from outside. For a singer where are the conditions? The vocal cords are two centimetres long, so what kind of conditions make a singer successful, the cords around, the body, language, intelligence? Most of the time you are talking to yourself as a psychological person, there are psychological reasons, you want more, and the vocal cords have to show strength all the time. An instrument where the strings are too strong, too tightly tuned, you can hear it. So I can’t change my cords. They are where they are, the quality is how they are, but the body is the instrument around, I can support the circumstances for these two cords. There’s a lot of potential, sometimes you can manipulate and sometimes you shouldn’t.

And this is all a kind of taste. Some teachers say, of course, you have to do this and that. I’m still working until I’m not a singer, is this the right decision or not? It’s a very interesting discussion always, and even harder to make a discussion on your own. I need always people around me who know me, my voice, and whom I can trust, my husband, trainer, coach, teacher, who give me a response, and my instinct is always to give space. Then I feel always a peace in myself and it can’t be wrong. In a Lieder recital it can’t be wrong when I feel space, freedom, you hear your notes flowing. You hear it sometimes when Lieder singers go for tough notes and it’s too strenuous and tight When I see that, I know there can’t be a relaxation in the cords. It should be a no-activity thing in your body – how can you support it in song? You should do nearly nothing [whistles], then you get space in the front for the public, they can see it in your face and they can hear it, because the voice is doing nearly nothing. You can train it, I’m training to do that…

As your recent recitals have borne out. (Below, Schwanewilms sings Strauss's "Wiegenlied"in Barcelona.)

I hope so. And this is one reason why I need these recitals to show me because nowadays all is activity, colours and loudness, all bustle, I haven’t got this opinion. Music is sometimes enough, and our civilization is always too loud, too much, we are losing the silence, the quality of doing nothing, of enjoying by doing nothing [laughs]

With a psychological activity to support it, or am I wrong?

No that’s the right word, psy-cho-logical [laughs].

Do you meditate?

No, not really, but I do a lot of Alexander Technique, for me it’s a form of meditation, because I calm down with the body, it tells me what condition I am, and sometimes it’s not nice [laughs].

That being your instrument, It must be difficult in the continental repertoire system – for that Rosenkavalier in Dresden, I understood you had only one orchestral rehearsal.

That being your instrument, It must be difficult in the continental repertoire system – for that Rosenkavalier in Dresden, I understood you had only one orchestral rehearsal.

It was a short rehearsal time with [conductor Christian] Thielemann. [Schwanewilms' Marschallin in that production pictured left]. Sometimes these are not the ideal circumstances to show the best quality in the relationship, it needs time of course, but this is also life. Thielemann doesn’t like to rehearse often, he’s very intense. I like it in a way but the main thing is then that I have to follow him, there’s no discussion, no communication, no asking, what do you like? But at that time I was surprised, I didn’t realize it to begin with, I realized it after the first performance, we did a general rehearsal. I realized at the premiere that he is a genius, a special conductor, he must have a phenomenal brain. He knew what I liked to support, and I couldn’t have known that in the rehearsal, he prepared the orchestra, one or two bars before, to prepare my line which he likes to support, and I was really touched by that because then I realized he is the one who remembers, he prepared the colours for my colour.

I have never met a person who reacts so quickly, and this means he is so tense, I couldn’t stand that [vivid impersonation follows]. But he is concentrating and is always thinking ahead. Rosenkavalier is a long opera, and it must exhaust him. But it’s a masterclass of brainwork. This is the reason why he is Mr Thielemann, why he’s so famous. He doesn’t talk a lot. And always... [the impersonation of fierce tension again]. But he is concentrated, how can he get this colour out of the orchestra. I find that really amazing.

You’d worked with him in Salzburg, on Christof Loy’s new production of Die Frau ohne Schatten. There must have been more long-term preparation there.

You’d worked with him in Salzburg, on Christof Loy’s new production of Die Frau ohne Schatten. There must have been more long-term preparation there.

And the Empress was a new role for me, I wasn’t always sure when I was studying the role, but I knew in parts what line I would like to take. So I’m not loudly insisting, but constantly insisting, please could you hear this, I would like to make a little rubato here. Some conductors are very sensitive and some not, and in his eyes I saw, no, yes, yes, mmm, maybe. So I was very clear after the first rehearsal that I could try some things again, he likes it, that he doesn’t like so much, so I can follow him to see what he wants to support. So it’s easy work in a way but also I have to concentrate so hard psychologically, to communicate without words [more impersonation]. But this is not completely right. This is what we understand immediately, but you see in his eyes, the orchestra is panting with fear, and as a singer you are much further away, you can’t lose him or you’re in trouble. What he doesn’t like he doesn’t show directly, but you feel it.

That must have been a strange process, partly because Loy had a vision of the fairytale opera as a 1950s recording-studio event, which none of us thought could work, and yet it mostly did, and that was your first acquiaintance with a very strange role.

I was already engaged for his idea, from the first day on, I know Christof and for me it was a clear language, he couldn’t deal with that fairytale story, he didn’t like it, so what shall we do? Nothing. We should follow him from the beginning on, and if I didn’t understand quickly what he wanted to support, I should have left. But I did understand, and I thought it’s a very good idea, for me it’s the best if you can’t deal with the fairytale.

I was in New York at the Met last November, in an old Wernicke production from 2002, he didn’t interpret a thing. I never met him – two months after that production he died, but he was a painter of wood and stone, he wasn’t a stage director, he didn’t describe why you should walk from that point to that point, there was no explanation, and I was completely free, and I loved that. But you as an actor, you are more responsible, and some can take it and some can’t. They are standing or walking and you think is there a reason? No, then you are not interested in the person. Wernicke was a light fantast, he was a colour fantast, he saw always pictures and dramas through lighting, brilliant, beautifully done. I couldn’t imagine how beautiful this piece could be on stage by telling only the story. One picture after another, nothing else.

But this was Wernicke. The stage was divided up, I was in one part and I could hardly see the conductor, and Vladimir [Jurowski] told me, this is the first time that I couldn’t see the singer… But the effect for the audience was breathtaking. I was put in a mirror box with a steep rake (pictured left). Very dangerous. I slipped twice and I had to go to hospital, but I was burning for it because in this mirror box every mirror was giving a different perspective, and in the audience the light was broken differently, everywhere stars, and I wanted to move like a bird with less weight. It worked, but I had to rehearse in this mirror box. For me, because it’s hard to sing this role and then with a lightness and ease of movement, I had to rehearse it. And even if it didn’t work immediately, I had to find the calm to do it again. This was really something. And I burned for it just as two years earlier I had burned for Christof’s idea, and I understood them both.

But this was Wernicke. The stage was divided up, I was in one part and I could hardly see the conductor, and Vladimir [Jurowski] told me, this is the first time that I couldn’t see the singer… But the effect for the audience was breathtaking. I was put in a mirror box with a steep rake (pictured left). Very dangerous. I slipped twice and I had to go to hospital, but I was burning for it because in this mirror box every mirror was giving a different perspective, and in the audience the light was broken differently, everywhere stars, and I wanted to move like a bird with less weight. It worked, but I had to rehearse in this mirror box. For me, because it’s hard to sing this role and then with a lightness and ease of movement, I had to rehearse it. And even if it didn’t work immediately, I had to find the calm to do it again. This was really something. And I burned for it just as two years earlier I had burned for Christof’s idea, and I understood them both.

And with Loy you were very much the centre of the opera, whereas the Empress can seem to disappear for long stretches.

That was his idea. I knew friends and colleagues in the audience who didn’t understand it, and at first I thought I wasn’t good enough because I couldn’t explain it through my body, but after a short time I found other people who did understand it.

It has the potential to be a complicated story. I don’t think it is.

I don’t think so either. But if you don’t think it’s complicated, you follow the fairy story scene by scene, and make no explanation and no interpretation. This is not Christof’s work, he’s always interpreting, and I accept this always when there is a logical answer for it. Then I can go for it, and I should find a way to show this opinion, but for me it was very good to see that this story works when you don’t interpret anything. In the end always a production is a question of how is the stage director working, is he or she an active force who wants to influence or not? Sometimes it’s working, and as an audience you have to accept it, or you don’t accept it and it doesn’t work. This is art. But the director also has to trust the music and not doubt too much. There are lot of doubters around us, a production from someone like that can offer many touching moments, but sometimes you think, this is too much, we lost the main thing, the music, I want to hear more music, and this is where I come back to space, quietness supports always space, or is supported by giving space.

That struck me with the Marschallin’s monologue. Dresden is a large house and I was sitting some distance from the stage, but I still felt drawn in by your quietness, I got that feeling that you were singing to me individually. I guess having a native singer who completely understands the text helps.

But it’s my way to sing and the Marschallin helps my capital. Usually it’s in recital that I can show most facets, I can show the subtext more by covering the voice, by setting the voice without vibrato. The Marschallin is talking, there are more recitatives than you think though Strauss sets none in form, this is parlando, a spoken style. I can support it with my technique, with my colours, like a painter, Strauss’s music sets Hofmannsthal’s text perfectly for these features.

Then there are the long lines, like the one which launches the trio, “Hab mir’s gelobt".

The soaring long line, I like it. This is the reason why I’m a Strauss soprano, and not a Wagnerian soprano, because a Wagnerian voice has more capital features in the middle range, in the dynamic potential, and I have limits there. I could sing more with the chest voice higher, but there would be consequences for my top, I don’t want that yet.

Is that why so many Wagnerian sopranos lose the body and the pitch at the top?

This is the reason, because when you start to put too much chest voice into the top, the result is that your high notes are getting narrowed, smaller, and sharper, which means lower pitch, it’s always too low, because your head voice is more going away. It’s unbalanced, and I know my voice needs time, doesn’t want to be pushed, so I have to take responsibility for that.

So is Sieglinde as far as you would go now?

I do like to sing it, I would like to sing it again, but in 2017-18, and Fidelio again, because everyone now expects that I’m a Strauss soprano and no-one expects that I will push my voice in the middle range. If a conductor or a house engages me they know what they get. So I haven’t pushed. I offered my proper potential and it has been accepted in the world. This is all right, I love singing Marschallin, Ariadne, Arabella (pictured right, above, by Monika Rittershaus with her "Mr Right"), Chrysothemis, Danae.

I do like to sing it, I would like to sing it again, but in 2017-18, and Fidelio again, because everyone now expects that I’m a Strauss soprano and no-one expects that I will push my voice in the middle range. If a conductor or a house engages me they know what they get. So I haven’t pushed. I offered my proper potential and it has been accepted in the world. This is all right, I love singing Marschallin, Ariadne, Arabella (pictured right, above, by Monika Rittershaus with her "Mr Right"), Chrysothemis, Danae.

Die Liebe der Danae is such a gorgeous, moving opera, and it’s a shame we’ve not had it in Britain this Strauss anniversary year.

It’s glorious, but It’s hard to find the cast. The bass-baritone for Jupiter is really hard to find, the voice range is high for a baritone. There’s a singer in Dresden, Hans Joachim Ketelsen. He was a house baritone in East Germany and was always asked if he wanted to jump into the tenor fach, and he denied always. But this was a good decision, because later he gave his voice time, so that the deep developed on its own and he could keep his high notes as a baritone. For that baritone it’s a brilliant role. Franz Grundheber has the high notes but not the deep ones, but he is a very good actor, so when he couldn’t support the deep notes you get something different – stage presence, so you didn’t miss anything.

Bryn Terfel might sing it.

It’s too high for him, I think. The deep notes are no problem for him, mmm, wonderful. But Strauss offered some possibilities to change the high notes. I have a picture of Strauss sitting on his bench with the score of Die Liebe der Danae, this typical score, wide frame and red and yellow colour for the letters, studying… This was the second last opera.

He thought it would be his last. Capriccio was an afterthought. Have you sung the Countess?

Not live. I would like to, but it’s rarely done. Once I was offered it and I couldn’t because I was already engaged.

There was a very beautiful production at Glyndebourne, set in the 1920s, the Strauss family didn’t like that so it was never filmed. Elisabeth Söderström sang it and then Felicity Lott.

[Wistful] Felicity Lott – a brilliant singer, very intelligent and a nice, nice, nice person. And she is English, you see, and yet she understands the German. There shouldn’t be a reason for a singer to show the public, oh I’m a foreigner. Sorry, it’s your activity or non-activity to say I understand this role. In Italy to sing Italian as a foreigner is not accepted. If there is any pronunciation not completely as they want to hear it, they are very rude. I didn’t experience this personally but I saw it in faces when I thought, the singer is making a brilliant Italian sound, so why are they complaining? But they complained loudly and very rudely, I didn’t like that. English people are different, they are always happy when you speak in English that they are not forced to talk in a different language, I love England for that.

You’ve sung at the Wigmore quite a bit. (Schwanewilms pictured left backstage with pianist Roger Vignoles after a recital last year.)

You’ve sung at the Wigmore quite a bit. (Schwanewilms pictured left backstage with pianist Roger Vignoles after a recital last year.)

Eight or nine times.

It’s a good space for you?

Boris Becker first went to Wimbledon when he was very young. And always in Germany he said this is my Wohnzimmer, my living room. And I say now, my Wigmore is my Wohnzimmer, I love it.

When you have a loyal public, the same people will come every time.

And they are the most educated public in the whole world. In Amsterdam you have a similar audience. You look and see some of them know every line, it’s unbelievable. I like it because I can risk a lot of subjective things which are not written officially in the score, but they understand it because they understand what the text is about, so they react directly, sometimes – I like that very much, I do like to get reactions.

Your Wagner Wesendonck Lieder was stunningly different, because it was so unforced, but then when you got the strong stuff, it was amazing, and people said in the interval, oh I never heard it sung like that. It can be too stentorian, but this was very lyrical and intelligent.

It should be. Because Wagner is very clear what he liked to support. He was the only one engaged to build up his own opera house. Why? He knew that he wanted a big huge sound but only the potential of it, 12, 14 violins, but in Bayreuth you can get a perfect pianissimo from such forces. I sang the Four Last Songs in Manchester with Markus Stenz in February. This orchestra [the Hallé] is typical for an English orchestra, is able to play piano. You start [she sings the opening lines] and think, oh, thank you, even in lower parts I hadn’t to push, never. Before and after I sang them somewhere else, but I promise, it was so loud. When you see the orchestral score, there are a lot of places when you think, if Strauss had lived to hear them he would have altered some of the dynamics. But the Hallé play with one single voice. As a conductor you take over the responsibility for that, but most conductors don’t take enough time for that. It takes time, to say, uh-oh, you hear, don’t follow him - I show you the sort of dynamic you should play, don’t follow your partner, trust me, look at me.

I t’s a question of building a relationship, like Mark Elder has in Manchester and Markus Stenz in Cologne.

t’s a question of building a relationship, like Mark Elder has in Manchester and Markus Stenz in Cologne.

The Hallé isn’t Markus’s orchestra, but they were really playing like Mark’s group. Lovely. And Wagner had the same idea. In several books you can read his idea about the singer’s relationship to the orchestra. It’s always the main idea that a singer must be heard, and the silence is the main thing which I want to offer. When you hear – [she sings the Valkyrie theme] – where’s the silence there? But there’s a misunderstanding.

The Wesendonck Lieder with piano are completely different, but you hear it in the score and read it. The main difference is the orchestra has the potential to play loud but to build up this atmosphere of pianissimo, or vibrato or echo but it doesn’t come into the front, it’s a holding back situation, and when it does come forward it’s overwhelming. With the original Wesendonck Lieder, there’s more a conversation between the singer and the piano, not an image of the orchestra colours. This means the singer should search for different colours. Then you realize you can support more the consonants, and make sense with this alliteration, which he loved so much.

Some Strauss Lieder were composed with orchestra and some were orchestrated later. You sing them in both versions - do you find cases where one works better than another?

Of course, and you hear the difference when someone else made the orchestration. Also Strauss is such a genius in setting words in music. In the operas, with Hofmannsthal there was a celebration of a relationship in word, text and music. Wagner composed his own words and line and you hear it. I hear immediately what Wagner wanted, but after a while there was no wedding with different influences. He wasn’t influenced much and so there was not a big development in his life. Strauss lost Hofmannsthal and went in different directions, but he still composed Die Liebe der Danae on an old suggestion of Hofmannsthal. He was looking back in the 1940s, he carried on living in Germany when the political system had been killed by the Nazis, he felt unjustifiably punished because he thought he’d done the right things, he helped Jewish people in his opinion, and other people punished him because he didn’t stand up in Germany and fight against the Nazis.

He was an old man by then.

And he hadn’t got this character – it was always music, music, and he didn’t take the Nazis seriously at first, he thought like a lot of people thought, they are really stupid, and he took the chance to be paid and do his job and had nothing to do with politics. It was a wrong thing to do. But when you’re looking back, you know every time what’s better. So Strauss was missing a lot and he filled it with this composition Liebe der Danae. I understand what his psychological situation was.

He’s a difficult person to read, there often seems such a gulf between the man and the work.

For me, it’s a typical English situation, English people learn how to hide themselves behind an image, sometimes very nice and easy to talk to someone, because they are always very friendly. I like that very much, but when you want to come a little bit closer, you realize, oh, there is not a chance to go further. Strauss was a person like that, and his wife Pauline was at that time very ill and he was pushed already into a retrospective situation, older times were better.

He immersed himself in Mozart and Goethe.

Older times, classical times, culture destroyed. How dare they do that? But that was his psychological situation, hiding himself more than before in a very Prussian way.

Though he was Munich-born, wasn’t he?

But he learned that and built up the façade more and more to hide himself and his unsureness – he was very disciplined, 9 to 12 composing, then from 2 to 5 and in between he was walking or eating or sleeping but it was a disciplined day. He was in control and Pauline was the opposite.

You have a wonderful talent for comedy. What about Intermezzo [a thinly veiled dramatization of an upheaval in the Strausses’ married life]?

It should be there. Capriccio, Intermezzo, these are big wishes on my top list. Please, responsible people, give me the chance to sing those, give me the time, and put them quite early in my calendar.

Would you go back to Glyndebourne [where she sang Weber's Euryanthe]? There’s good preparation there. Vladimir Jurowski was always around from the first rehearsal, and now Robin Ticciati is too.

Would you go back to Glyndebourne [where she sang Weber's Euryanthe]? There’s good preparation there. Vladimir Jurowski was always around from the first rehearsal, and now Robin Ticciati is too.

For Capriccio that would be perfect. Intermezzo I looked into, there are several scenes I liked, but there is no red line through. Capriccio I did so it is easy for me, perfect for Glyndebourne. Intermezzo, I’m not sure yet.

Christine [the Pauline character] needs real charm. Too often she can be seen as a termagant, a nightmare person.

No, I’m sure she isn’t, she can come across that way. It’s because of insecurity - she is a more introvert person than her husband, she reacts in a different way to hide herself, to seem extrovert. The Marschallin or Capriccio Countess must never be extrovert, you use very small gestures and it fills the room. In Intermezzo the main interest for me is that there's always a reason for a big reaction, a tantrum, two pages before it happens, or one line before, and it should be not loud but directly seen why the change is so huge or why she’s bad. She is very, very intelligent but not well treated, so to show the history of the character is important. [Janáček’s The] Makropoulos [Case] is sometimes similar.

Have you sung the role of Emilia Marty?

I would like to, but this is a completely different role, bright middle range. But if a conductor wants me… I was asked in the past, 30 times, Salome and Makropoulos. Salome I will never sing because the orchestra is too big, it’s not really a chance to show the intimacy, he wasn’t interested in that, I have no chance then. With Chrysothemis [in Elektra, pictured above by Clive Barda in the Royal Opera production], there are tiny indications of intimacy – like when she sings "der Vater der ist tot", this is a reason for me to sing a role, Salome is always extrovert, exhibitionism, I’m not the right type. But in Makropoulos, there are a lot of chances – I would like to do that. At that time it was the same reason, the big middle range, oh no, stop it, it’s too early - but now 2017, 18, 19, let’s see.

One big question – could you, would you, sing Isolde?

I’m not sure. “Mild und leise” [the so-called Liebestod] is on the new Wagner CD. I would like to study the whole role but I must try it out first in a concert, to see how I feel, because there are some intimate parts which interest me, there are somehow places - in a room with a piano I can sing it, but on stage the question is how can I keep my voice clear enough for the intimate places.

Margaret Price recorded it, memorably, for Carlos Kleiber, and never sang the role on stage..

I heard that once years ago, and this is my idea of an Isolde. For me many factors come into play: I need a staging that’s intimate, not expressionistic, and a conductor who’s interested in keeping the orchestra down. Then I will say yes. If it doesn’t come, then I will deny it. My quality is obviously more in the silence than in the loudness. Trust me, trust the music and the line. Perhaps I’ll never sing Isolde in my life, but this is my taking care of myself. If I feel free then there’s a result, people will understand why I want to sing that kind of role, otherwise they won’t. I always want to feel comfortable on stage.

- Anne Schwanewilms sings the Marschallin in excerpts from Der Rosenkavalier at the Barbican on Thursday

- David Nice's blog on the June 2013 Dresden Rosenkavalier

Overleaf: watch the trailer for Anne Schwanewilms's new Wagner recording, beginning with "Träume" from the Wesendonck Lieder

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment