Boris Giltburg, Queen Elizabeth Hall | reviews, news & interviews

Boris Giltburg, Queen Elizabeth Hall

Boris Giltburg, Queen Elizabeth Hall

Idiosyncratic depth in shadowlands Rachmaninov, Prokofiev and Ravel

Among the diaspora of younger-generation Russian or Russian-trained pianists, there are at least four whose intellect and poetry match their technique. Three whose craft was honed at the Moscow or St Petersburg Conservatories – Yevgeny Sudbin, Alexander Melnikov and the inexplicably less well-feted Rustem Hayroudinoff – have made England their home.

The last few minutes of Ravel’s La Valse, though, are as unambiguously terrifying as anything in 20th century music

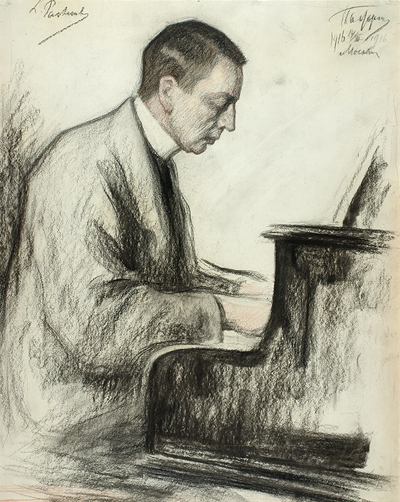

It’s even tempting to go overboard and say that Giltburg’s individuality matches the three major pianist-interpreters of their own music on the programme (Rachmaninov pictured below by Leonid Pasternak, Prokofiev and Gershwin; Ravel and Sibelius stand outside that charmed circle, but the transcription of La Valse sounded as if it could only have been written by a virtuoso). The sequence of Rachmaninov’s ten Op. 23 Preludes was an awfully big adventure only partly in this world, beginning in veiled anxiety with two-note figures obsessing around a mid-range disquiet and ending with perfect peace.

Not only did Giltburg make sense of the psychologically satisfying contrasts between the composer’s many facets of his own personality, moving without a pause from one to another; he also reflected Rachmaninov’s wayward mastery in rounding off each pieces. And in terms of artistry – with lack of the usual pedal mashing on last chords almost incidental, but so satisfying – that’s the sign of a great artist. If the poise of the D major idyll and the drama of the ensuing G minor cavalcade anchored the nervous disposition of the whole, it was the flight of the eighth prelude which truly dazed and deliciously confused this particular soul.

Only one thing slightly worried me and continued to do so in the second half – the lack of real brilliance in the right-hand treble. Was this Giltburg’s own imbalance or a shortcoming of the otherwise rich, colour-friendly Fazioli piano on which he plays? Possibly neither; a colleague who wasn’t writing up the concert told me that from his seat on the other side of the hall, the fault if any sounded like an over-brilliant top and a less distinct bass.

Only one thing slightly worried me and continued to do so in the second half – the lack of real brilliance in the right-hand treble. Was this Giltburg’s own imbalance or a shortcoming of the otherwise rich, colour-friendly Fazioli piano on which he plays? Possibly neither; a colleague who wasn’t writing up the concert told me that from his seat on the other side of the hall, the fault if any sounded like an over-brilliant top and a less distinct bass.

The last wasn’t a problem for me in ferocious tramplings of troubled introspection of Prokofiev’s Eighth Piano Sonata. Clarity of inner lines charted the – by the 1940s - sadder and wiser Prokofiev’s rich interior life; the point in the opening Andante dolce where time freezes came as a voice from another planet. It was a shame, though, that Giltburg rushed another tolling figure in that first movement and the central juggernaut of the dazzling finale. I didn’t buy the Ashkenazy quotation in Harriet Smith’s programme note relating it all to the war, but the shattering conclusion tallied with hers: “Prokofiev’s triumphant ricocheting coda is surely as mocking and emotionally ambiguous as anything to be found in Shostakovich”.

The last few minutes of Ravel’s La Valse, though, are as unambiguously terrifying as anything in 20th century music. On the way to the abyss, his third version of this dazzlingly-scored tone poem – “a painting of a ballet”, as Diaghilev labelled it – sounded so Lisztian, with invented swirls including a whole-tone newcomer changing the perspectives of the orchestration we usually hear so radically, that I had to check whether or not Giltburg had added virtuoso touches of his own (update, contradicting the original report: he had). What a neat rejoinder to give another unfamiliar piano version as the first encore, a more chaste edition of Sibelius’ Valse triste.

So in effect we had a chain of dances – minuet (Prokofiev’s second movement), tarantella (his finale) and two waltzes. Giltburg then broke into a frenetic galop, the panicky flight of Red Riding-Hood from the Wolf in the sixth of Rachmaninov’s Op. 39 Etudes-Tableaux – this pianist must give us the whole masterpiece next time – before relaxing into another transcription, his own at last, from Gershwin’s fabulously insouciant four-hand piano roll version of “That Certain Feeling”. Giltburg contorts himself into so many odd positions to get the sounds he wants – most alarmingly as a version of the Caterpillar as illustrated by Tenniel for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, curved over the keyboard – that it was good to see him so upright, free and easy in another style he adopts to the Fox Trot manner born.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

Add comment