Kadouch, Vincent, BBC Singers, BBCSO, Minkowski, Barbican | reviews, news & interviews

Kadouch, Vincent, BBC Singers, BBCSO, Minkowski, Barbican

Kadouch, Vincent, BBC Singers, BBCSO, Minkowski, Barbican

Blockbuster programme of sacred, profane, exquisite and downright bonkers French music

Back at the Barbican for a new season after a Far Eastern tour, the BBC Symphony Orchestra returned to pull off a characteristic stunt, a generous four-work programme featuring at least one piece surely no-one in the audience woud have heard live before. This time, the first quarter belonged exclusively to the unaccompanied BBC Singers in one of the most demanding sets of the choral repertoire.

Serious intent was there at all times, but determinedly so in Figure Humaine, Poulenc’s Second World War settings of lyrics by Paul Éluard posted to him by the poet's Resistance colleagues (and given a March 1945 London premiere by the BBC Singers' predecessors). The anger and the pity of the Second World War are here through a many-voiced filter of quiet and ironic numbers, building in "La menace sous le ciel rouge" to fever pitch and then a rocking aftermath, spiritual sequel to the end of Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms.

Yet that’s not all: Éluard and Poulenc have a final trail to blaze in the epilogue-like hymn to ‘Liberté’, the word not uttered until the last ecstatic quatrain with a soprano hitting a top E (the one just below the Queen of the Night's F in alt). Accomplished though an augmented BBC Singers undoubtedly were, a few stray vibratos sometimes defused the focus and made one fear for the pitch in tricky sequences, though it did in fact hold. I fell in love with Figure humaine on the choral group Tenebrae’s stunning recording, and this was just a notch below.

Yet that’s not all: Éluard and Poulenc have a final trail to blaze in the epilogue-like hymn to ‘Liberté’, the word not uttered until the last ecstatic quatrain with a soprano hitting a top E (the one just below the Queen of the Night's F in alt). Accomplished though an augmented BBC Singers undoubtedly were, a few stray vibratos sometimes defused the focus and made one fear for the pitch in tricky sequences, though it did in fact hold. I fell in love with Figure humaine on the choral group Tenebrae’s stunning recording, and this was just a notch below.

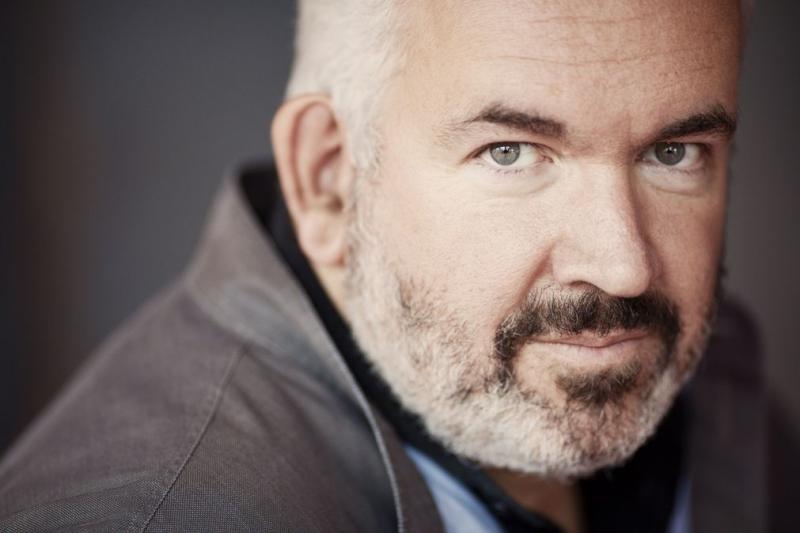

Poulenc’s Concerto for Two Pianos, on the other hand, was blessed with a performance fit for laughing gods and weeping mortals. Minkowski had the solution to any orchestral thickness which should have been adopted last Wednesday by Nézet-Séguin, where the soloist in the Piano Concerto, Alexandre Tharaud, was often swamped – that’s to say, to set the orchestra back and give the spotlight to the two pianists. Though apparently no established duo in this piece like the Labèque Sisters who used to make it so delightfully ubiquitous, David Kadouch (pictured above) and Guillaume Vincent (below) offered the necessary mix of different temperaments with complementary musicianship - young musicians both very much on the way up. Kadouch would provide more introspective rejoinders to Vincent’s obvious playfulness – heartbreakingly so in the pathos which turns the Mozart pastiche of the slow movement into something meaningful.

Both pianists made you realize what trailblazing genius Poulenc showed in his scintillating punctuations of music-hall turns and cinematic heart with Balinese gamelan music. The orchestra was in top, razor-sharp form, too, and first cellist Graham Bradshaw’s solo on harmonics capped the many miracles. But there were more to come in what had been advertised as Ravel’s Ma mère l’oye (Mother Goose) Suite but turned out to be the complete ballet – praise be, for its extra music continues the line of metaphysical subtlety in orchestration and melody. Here the BBC woodwind proved themselves, as ever, the equal of the world’s best. Flautist Daniel Pailthorpe, oboist Richard Simpson and clarinettist Richard Hosford filled Minkowski’s slow tempi for the sadder fairy-tale episodes with meaning; there were mysteries, too, from harpist Louise Martin and leader Stephen Bryant.

Both pianists made you realize what trailblazing genius Poulenc showed in his scintillating punctuations of music-hall turns and cinematic heart with Balinese gamelan music. The orchestra was in top, razor-sharp form, too, and first cellist Graham Bradshaw’s solo on harmonics capped the many miracles. But there were more to come in what had been advertised as Ravel’s Ma mère l’oye (Mother Goose) Suite but turned out to be the complete ballet – praise be, for its extra music continues the line of metaphysical subtlety in orchestration and melody. Here the BBC woodwind proved themselves, as ever, the equal of the world’s best. Flautist Daniel Pailthorpe, oboist Richard Simpson and clarinettist Richard Hosford filled Minkowski’s slow tempi for the sadder fairy-tale episodes with meaning; there were mysteries, too, from harpist Louise Martin and leader Stephen Bryant.

It was hard after this to adjust at first to the raucous world of late developer Albert Roussel, who, turned 60 in 1930, turned out a stamping, berserk compendium of the late romantic style in which he grew up and fashionable age-of-steel mechanics in his Third Symphony. Minkowski gave a wink at the dance-fun to come in the middle of the unstoppable first movement while those woodwind luridly kicked off a surprise in the middle of the Adagio’s wallow – a crazy fugue which brings the romanticism out in boils. With the scherzo and finale, though, it was all fairground craziness, Chabrier on acid, a delirious way to be thrown off the evening’s rainbow-painted carousel.

- Listen to this concert for the next six days on the BBC Radio 3 iPlayer

- Read about an outstanding 2009 Proms performance of Ravel's complete Mother Goose ballet on David Nice's blog

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Add comment