theartsdesk in Dresden: Wagner and Vivaldi at the 2013 Dresden Music Festival | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Dresden: Wagner and Vivaldi at the 2013 Dresden Music Festival

theartsdesk in Dresden: Wagner and Vivaldi at the 2013 Dresden Music Festival

Wagner and Vivaldi go head to head in a festival of old and new

Sitting in the concert hall in Dresden’s Albertinum – the city’s modern art gallery – is a paradoxical experience. You are indoors, but faced on all sides by external walls, framed by Dresden’s typical bourgeois 19th-century architecture but looking up to a giddyingly contemporary, asymmetric ceiling. Neon-lit signs cover one wall, while the other gives way to a gallery of classical sculpture.

Synonymous with the destruction that killed some 25,000 people and obliterated 15 square miles of the city in the closing months of World War II, even a decade ago Dresden was still dominated by architectural scar-tissue. Bombed-out blocks gave the lie to the impeccably reconstructed buildings they neighboured and violent juxtapositions of 70s brutalism and neo-classical pomp offered contradictory accounts of a troubled history.

It was the brass's characterful contributions that set the tone of end-of-term musical hijinks

But the Dresden of 2013 is a different creature. Gaps remain in the skyline of the Aldstadt, but these are the exceptions among the uniformly lovely rows of pastel-pretty facades, and only the blackened bricks of the iconic Frauenkirche (pictured below) – preserved from the ruins until they could be restored once again – remain to speak softly of what has passed.

From Orlandus Lassus, Lotti, Hasse and Bach, Schumann, Strauss and of course Wagner, Dresden has been at the centre of classical music’s development over four centuries. The city’s complex political history has only been matched by its nexus of cultural encounters – a place of conversation and negotiation between Lutheran austerity and Romantic excess, home to the mighty Dresden Staatskapelle and the Saxon State Opera.

The city’s annual classical festival may only be in its 36th season, but has its roots in musical history that stretches far further back. Concerts take place across the city, in the Semperoper where Der fliegende Holländer, Tannhäuser, Der Rosenkavalier, Salome and Elektra all had their premieres, the Frauenkirche where Bach once gave a recital, the Catholic Cathedral, neo-classical Schloss Albrechtsberg overlooking the Elbe and the baroque fantasy of the Schloss Pillnitz. Under General Director Jan Vogler (once himself the principal cellist of the Staatskapelle) a tired festival has found a new lease of life, reinventing itself just as the city around it has, and maintaining the same balance between honouring the past and celebrating the new.

The city’s annual classical festival may only be in its 36th season, but has its roots in musical history that stretches far further back. Concerts take place across the city, in the Semperoper where Der fliegende Holländer, Tannhäuser, Der Rosenkavalier, Salome and Elektra all had their premieres, the Frauenkirche where Bach once gave a recital, the Catholic Cathedral, neo-classical Schloss Albrechtsberg overlooking the Elbe and the baroque fantasy of the Schloss Pillnitz. Under General Director Jan Vogler (once himself the principal cellist of the Staatskapelle) a tired festival has found a new lease of life, reinventing itself just as the city around it has, and maintaining the same balance between honouring the past and celebrating the new.

It was the past however that dominated a visit to this year’s festival – inevitable, perhaps, in this 200th anniversary year of Dresden’s most celebrated musical son Richard Wagner. But, working up to full-blown Romanticism, we started a little further back in time with music from Handel, Vivaldi, Hasse and Dresden’s own Heinichen and Fasch.

2012 saw the launch of the Dresdner Festspielorchester – a one-night-only ensemble of Europe’s finest early instrumentalists under the direction of Ivor Bolton, establishing what looks to become a regular fixture of the festival. There’s often a complacency to such ad hoc groups, especially in core repertoire where default can easily override the energy of actual creativity. But Bolton’s love of this repertoire is such that he has no difficulty carrying his musicians along with him in a romp through some of the more attractive highways (and, admittedly, more abstruse byways) of baroque music.

2012 saw the launch of the Dresdner Festspielorchester – a one-night-only ensemble of Europe’s finest early instrumentalists under the direction of Ivor Bolton, establishing what looks to become a regular fixture of the festival. There’s often a complacency to such ad hoc groups, especially in core repertoire where default can easily override the energy of actual creativity. But Bolton’s love of this repertoire is such that he has no difficulty carrying his musicians along with him in a romp through some of the more attractive highways (and, admittedly, more abstruse byways) of baroque music.

It helps that this is a properly generous band (balancing up to some 12 violins), setting the acoustically challenging vault of the Albertinum throbbing with vividness and clarity, with brass especially delighting in the rustic virtuosity of these orchestral concertos. It was their characterful contributions that set the tone of end-of-term musical hijinks, overpowering the banality of Fasch’s Suite in D major with sheer force of will, and offering up a superb rendition of the horn duet that is the centrepiece of Heinichen’s Concerto in F for solo Violin, Oboes, Flutes and Horns. Of the less familiar works on the programme this was the keeper, a textural gem whose adagio sets a solo flute against a frothy backdrop of plucked strings (strummed here, guitar-like, by the whole section).

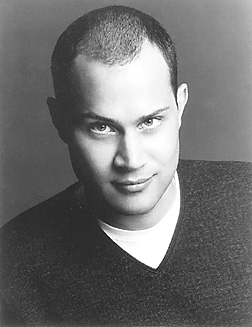

Giving the orchestral brass a run for their money was countertenor soloist Bejun Mehta (pictured above). We don’t see nearly enough of Mehta in the UK, so it was a delight to hear him storm and thunder his way through some of the best bits of baroque opera. Hasse had a brief outing with the opener, “Dei di Roma” from Il Trionfo di Clelia, showcasing Mehta’s trumpet-like projection and his enormous range. Cruelly challenging as Handel never is, Hasse demands much of his soloists, but even in extremity Mehta never lost his grip on the dramatic string through the coloratura labyrinth and led us safely out in grand style. Handel’s beloved “Vivi Tiranno” offered still more swagger, and a foaming torrent of da capo ornamentation, but it was “Stille Amare” from Tolomeo and the gorgeously understated “Non fu gia men forte Alcide” from Orlando that Mehta’s upper register came into its own, spinning the most delicate of pianissimos over the orchestral surge.

Giving the orchestral brass a run for their money was countertenor soloist Bejun Mehta (pictured above). We don’t see nearly enough of Mehta in the UK, so it was a delight to hear him storm and thunder his way through some of the best bits of baroque opera. Hasse had a brief outing with the opener, “Dei di Roma” from Il Trionfo di Clelia, showcasing Mehta’s trumpet-like projection and his enormous range. Cruelly challenging as Handel never is, Hasse demands much of his soloists, but even in extremity Mehta never lost his grip on the dramatic string through the coloratura labyrinth and led us safely out in grand style. Handel’s beloved “Vivi Tiranno” offered still more swagger, and a foaming torrent of da capo ornamentation, but it was “Stille Amare” from Tolomeo and the gorgeously understated “Non fu gia men forte Alcide” from Orlando that Mehta’s upper register came into its own, spinning the most delicate of pianissimos over the orchestral surge.

Balancing Mehta for the orchestral numbers was violinist Giuliano Carmignola – the soloist among soloists for Vivaldi’s Concerto Per la Solennita di S. Lorenzo. Even in the Albertinum’s misty, church-like, acoustic it was evident that Carmignola (pictured above) wasn’t on finest form, fudging his way through runs and colouring some distance outside the lines of accurate intonation. Apparently illness was to blame, but whatever the cause it couldn’t diminish the violinist’s irrepressible energy. Bolton has created an orchestra of individuals, with none more distinctive than this veteran musician. In a triumph of personality over technique he guided us through the massive accompagnato cadenza that is the Grave, all nervy arioso mood swings, and into the final virtuosic straits of the Allegro.

From the clean lines of the Albertinum to the gilded and tiered Semperoper (pictured below). Sprawled on the bank of the Elbe, even proximity to the Zwinger palace (now home to the city’s magnificent art collections) cannot diminish this monument to “Dresden baroque” – painstakingly rebuilt after the war, like so much of the city. A composer more associated with the Semperoper than perhaps any other is Richard Wagner. Although it’s hard to sift through the myth-making and fictionalising that surrounds the man (there’s even an exhibition at Dresden’s own city museum until August 2013 entitled “Richard Wagner in Dresden: Myth and History”), we can at least be certain of the significant role that Dresden played in his working life – home not only to Wagner and his family, but also to some of his greatest operas. Employed as assistant Kapellmeister at the Semperoper in its previous incarnation, Wagner conducted the orchestra that would eventually become the Staatskapelle.

Whether or not, as some claim, the composer left the indelible imprint of his sound on the ensemble, there’s no doubting the affinity they show for Wagner’s music under the direction of their new principal conductor Christian Thielemann. A celebration concert on the eve of Wagner’s bicentenary birthday brought Bayreuth’s unofficial music director together with the Staatskapelle and tenor Jonas Kaufmann (as well, in the most luxurious of encores, as the Saxon State Opera chorus) for the headline concert of this year’s Dresden Music Festival.

Whether or not, as some claim, the composer left the indelible imprint of his sound on the ensemble, there’s no doubting the affinity they show for Wagner’s music under the direction of their new principal conductor Christian Thielemann. A celebration concert on the eve of Wagner’s bicentenary birthday brought Bayreuth’s unofficial music director together with the Staatskapelle and tenor Jonas Kaufmann (as well, in the most luxurious of encores, as the Saxon State Opera chorus) for the headline concert of this year’s Dresden Music Festival.

Though hard to beat for sheer star-power, the combination of Kaufmann and Thielemann is not altogether a natural one. Thielemann’s darting, surging approach, driving the music constantly forward to an always-deferred point of climax, sits in direct conflict with Kaufmann’s rather more incremental, delicate approach. Yet, with the Dresden Staatskapelle to mediate, the moments where these two titans came together were remarkable.

Rienzi’s glorious Act V prayer “Allmächt’ger Vater” would have stirred even a less Wagner-susceptible city than Dresden to action, the other-wordly string theme of the opening transmuted almost imperceptibly into Kaufmann’s own melody. Thielemann invests his strings with a fluttering energy, re-investing even the longest of sustained chords or cantilenas with new dramatic friction and intent in each moment. It’s a very vocal way of playing, and one that works perhaps even better in the pianissimo, quasi-stillness of the Act I Overture from Lohengrin as in the tempestuous churnings of Der fliegende Holländer.

Kaufmann (pictured left) brought the intimacy of the salon to the opera house in “Inbrunst im Herzen” from Tannhäuser, connecting Wagner to his German Romantic lineage, to the intensely subjective, personal voice of the verses of Heine and Eichendorff and songs of Schubert, even as Thielemann’s weightier approach anchored us to the universal national legends. Thielemann’s Wagner is never less than heroic, and here the Statskapelle’s brass came into their own, horns ever-triumphant over the orchestra with their golden richness.

Kaufmann (pictured left) brought the intimacy of the salon to the opera house in “Inbrunst im Herzen” from Tannhäuser, connecting Wagner to his German Romantic lineage, to the intensely subjective, personal voice of the verses of Heine and Eichendorff and songs of Schubert, even as Thielemann’s weightier approach anchored us to the universal national legends. Thielemann’s Wagner is never less than heroic, and here the Statskapelle’s brass came into their own, horns ever-triumphant over the orchestra with their golden richness.

A sole foray away from Wagner mid-programme was intended to have been the premiere of Hans Werner Henze’s Isolde’s Tod, but practical issues in preparing the score gave us his 1999 Fraternite instead – an orchestral tone-poem whose textural effects pay more than a passing debt to Wagner. It’s not Henze at his absolute finest, but it was a welcome and necessary shift of pace, offering us some aural and critical distance on a necessarily over-laden evening of music.

Filing silently into the auditorium during the closing applause, enclosing us among them, Dresden’s own opera chorus joined Thielemann and the orchestra for the “Einzug der Gäste” from Tannhäuser. Quite literally immersed in Wagner, it would be hard to imagine a finer celebration for this anniversary, nor a more fitting climax to Dresden’s Music Festival. This is a city that embraces its culture, and while a memorable evening for all of us suited-and-coiffed inside the opera house it seemed to be an equally joyous occasion for the crowds gathered outside, watching the spectacle play out on a big screen as though it were a football match. Dresden’s reinvention doesn’t stop with its architecture; a contemporary, democratic spirit imbues almost everything that takes place here, as people reclaim an identity and a cultural legacy denied to them for so long. The festival is no exception: lively, diverse and unashamedly high-brow, it’s the soundtrack to a city understandably proud of its legacy.

- The 2014 Dresden Music Festival takes place between May 23 and June 10, 2014

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

Add comment