Der Fliegende Holländer, Royal Opera | reviews, news & interviews

Der Fliegende Holländer, Royal Opera

Der Fliegende Holländer, Royal Opera

The Royal Opera's Flying Dutchman never quite takes off

Whether or not we believe Wagner’s retrospective rebranding of the opera as a prototype music-drama, “a complete, unbroken web”, Der Fliegende Holländer reliably makes for a vivid evening’s entertainment. Which makes it all the more strange that this is only the work’s third outing at the Royal Opera in almost 20 years.

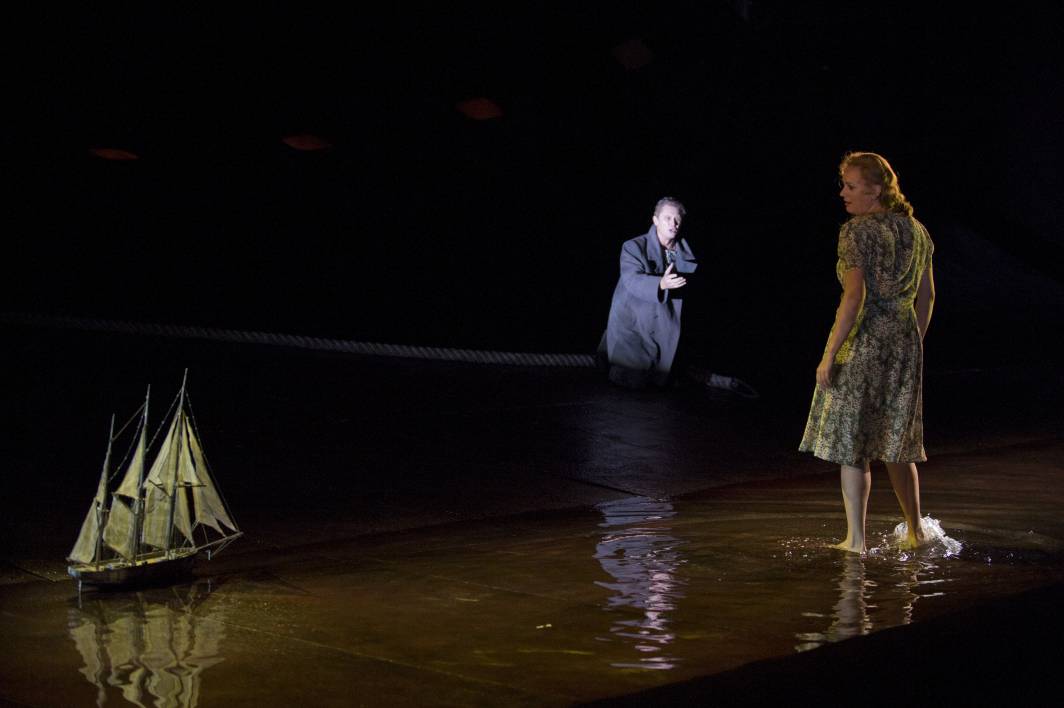

Greeted favourably when it debuted in 2009, the production relocates the folk tale of the arrogant mariner, forever condemned to wander the oceans unless he can be redeemed by the true love of a woman, to a non-specific contemporary setting. While a beautiful three-masted ship is present on stage, this model is dwarfed by the contemporary abstraction of a vessel that designer Michael Levine creates, its sweeping metallic curves by turns cradling the fragile action and then rearing up to hurl the Dutchman and his doomed Senta to their separate fates.

The psychological authenticity of the crazed fantasist Kampe creates in Senta comes at a vocal priceWe open, however, with one of Albery’s few missteps. The fretting exposed strings and horn cries that announce the Overture summon movement from the gauze curtain shielding the stage. For its full 10 minutes, and through the music’s many mood swings, the storm rages on in the curtain, accompanied eventually on a too-swift rotation by a searchlight that rakes blindingly over the audience. The 20th-century equivalent of those 18th-century operatic wave machines, this filler of a gesture is unworthy of what follows, distracting from Wagner’s score while adding little by way of drama.

The 2009 staging marked the return of Bryn Terfel to Wagner after his withdrawal from the Ring, his tormented, impassioned Dutchman central to Albery’s vision. While his Senta (Anja Kampe) returns for this revival, Terfel’s ghostly waders are here filled by the Latvian Egils Silins, a late replacement for Falck Struckmann. While his “Die frist ist um” didn’t quite find the bleak place it needed, interiorising the burden Albery heaps visually on him in the coil of rope that weighs python-like around his shoulders, he nevertheless found the tragedy that the composer recognised among the ironies of Heine’s satirical tale. His inability to unbend either physically or emotionally (aided in its stylised stiffness by David Finn’s Gothic lighting) gained pathos in the love duet, where Albery’s direction freezes the Dutchman and Senta to their separate spaces even as Wagner warms the music to boiling point.

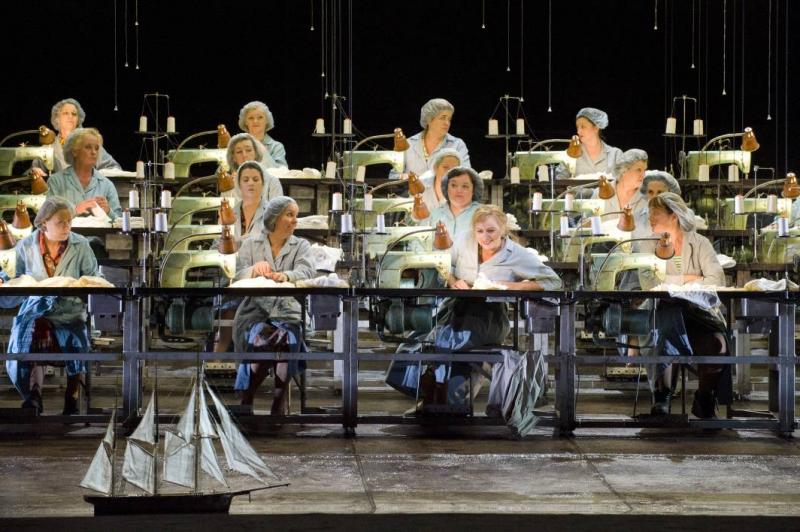

While some will be delighted by Kampe (pictured right with Silins), by her fearless attack of the extreme singing this role requires, the psychological authenticity of the crazed fantasist she creates in Senta comes at a vocal price. We see (and hear) the big fences coming, and while truth demands that she hurl herself at them with little care for beauty, at times the effect often crosses the line between artful disarray and actual lack of control. Her Ballad remains beautifully judged, a disquieting foil to the spinning song (wittily translated to a Western European garment factory).

While some will be delighted by Kampe (pictured right with Silins), by her fearless attack of the extreme singing this role requires, the psychological authenticity of the crazed fantasist she creates in Senta comes at a vocal price. We see (and hear) the big fences coming, and while truth demands that she hurl herself at them with little care for beauty, at times the effect often crosses the line between artful disarray and actual lack of control. Her Ballad remains beautifully judged, a disquieting foil to the spinning song (wittily translated to a Western European garment factory).

Also returning is John Tessier’s Steersman, whose legato makes a jewel of his love song, glittering like the Dutchman’s treasures against the matter-of-fact Daland (a rather under-characterised Stephen Milling). Endrik Wottrich makes an equally unremarkable job of Erik, his voice giving way in rather spectacular style under the weight of his closing confrontation with Senta, but his tensions were merely the most magnified of the evening’s singing as a whole.

The ensemble shuddered like Wagner’s stormy ocean, with Silins and the otherwise strong male chorus among the most at odds with the orchestra. Jeffrey Tate, striving for the more deliberate control and pacing that would make sense of the Dresden ending, found a no-place in his tempi that lacked either poise or real direction, creating unsightly tears in the musical cloth. Doubtless it will all settle, but with the complexities (and often noise) of Levine’s set still not fully worked out either, the effect was scrappy and distracting.

Issues of execution aside, Albery’s production remains a strong one, its muted simplicity daring to make something “rich and strange” out of Wagner’s awkward drama. This isn’t quite the impassioned love story Der Fliegende Holländer sometimes can be (and many will take issue with the ending), but in its place we get a meditation on human isolation and yearning that runs altogether deeper.

- Der Fliegende Holländer is at the Royal Opera House until 4 November

Buy

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows

Intimacy yields to spectacle as Beethoven's light of freedom triumphs

Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows

Intimacy yields to spectacle as Beethoven's light of freedom triumphs

Dangerous Matter, RNCM, Manchester review - opera meets science in an 18th century tale

Big doses of history and didaction are injected into 50 minutes of music theatre

Dangerous Matter, RNCM, Manchester review - opera meets science in an 18th century tale

Big doses of history and didaction are injected into 50 minutes of music theatre

Mazeppa, Grange Park Opera review - a gripping reassessment

Unbalanced drama with a powerful core, uninhibitedly staged

Mazeppa, Grange Park Opera review - a gripping reassessment

Unbalanced drama with a powerful core, uninhibitedly staged

Add comment