Hymn/Cocktail Sticks, National Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

Hymn/Cocktail Sticks, National Theatre

Hymn/Cocktail Sticks, National Theatre

A gentle trip down memory lane sees Bennett back at his best

“You don’t put yourself into what you write, you find yourself there.” It’s a maxim that has guided a writing career that, insect-like, has made itself at home among the lived detritus of autobiography and memoir. In Alan Bennett’s 2001 Hymn and his latest short-play Cocktail Sticks the author sets out in search of himself once more, finding on his quest not only his own history but that of a generation and an age at an ever-increasing remove from our own.

To anyone familiar with Bennett’s writing the story of the young Alan’s upbringing in wartime Leeds, of his relationship with his butcher father and socially aspiring mother, is well-worn ground. Cocktail Sticks deliberately treads in the footsteps of Bennett’s 2010 memoir A Life Like Other People’s, and Hymn doesn’t wander too far from its themes either. But somehow this gentle pairing of fragments – a set of variations on a theme – coalesce into a clear-sighted picture, perfect for the Sunday afternoon slots that the National Theatre has scheduled.

Echoes and repetitions are built into the visual fabric of the plays, staged here by Nicholas Hytner and designer Bob Crowley among the dust-sheet-covered sets for Bennett’s current play People. The tentative occupation of Hymn (just an armchair, a wireless and a string quartet) gives way to the more sprawling clutter of Cocktail Sticks as the author’s fiction and dramatic fantasy co-exist in a quietly contested space.

Echoes and repetitions are built into the visual fabric of the plays, staged here by Nicholas Hytner and designer Bob Crowley among the dust-sheet-covered sets for Bennett’s current play People. The tentative occupation of Hymn (just an armchair, a wireless and a string quartet) gives way to the more sprawling clutter of Cocktail Sticks as the author’s fiction and dramatic fantasy co-exist in a quietly contested space.

Featuring both music and words in its playtext, Hymn was originally a commission from the Medici Quartet to composer George Fenton. He invited his long-time collaborator Bennett to join him, and the two created a homage to that very particular spirit and sense of Englishness that lives between the wax-crusted pages of Hymns Ancient and Modern – the “weightless baggage carried down the years.”

Fenton (best-known for his music for Gandhi and The Madness of King George) is a chameleon, never happier than speaking in someone else’s musical voice. Here he flits between the accents of César Franck, Delius, Frank Bridge and even a palm court orchestra, quoting from Elgar’s mighty oratorio The Dream of Gerontius and of course from the great English hymn tunes that score Bennett’s childhood. Members of the Southbank Sinfonia evoke attempted violin lessons from Bennett’s father and also his brief flirtation with the double-bass, supporting and occasionally dominating a narrative that slips associatively between word and music.

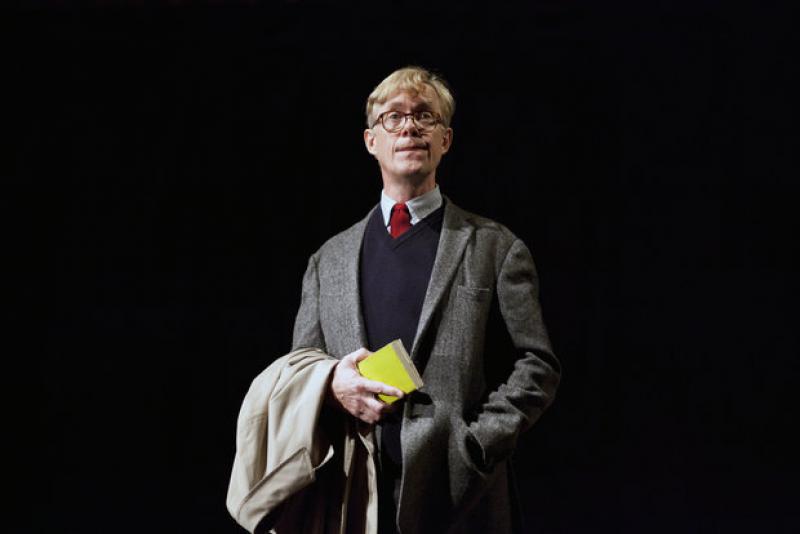

The prose, as ever, is wickedly precise, whether it’s a description of Bennett’s reverent fascination for his father’s violin, or the experience of a symphony heard from above the bass section – “like watching a circus from behind the elephant.” Alex Jennings (pictured above with Derek Hutchinson) is uncanny as Bennett (it helps that he’s a dead ringer for him), complete with sloping shoulders, apologetic stance and of course the laconic burr of his Leeds accent. It’s a performance whose mimickry is so exact as to lose its actor in his subject, and continues seamlessly into Cocktail Sticks, which unites Bennett in conversation with his now-dead parents.

Gabrielle Lloyd (pictured left with Jeff Rawle) is all fragile hope and weathered acceptance as Mam, yielding some of Bennett’s finest comedic writing over her yearnings for those social symbols of avocado pears, artichokes, and of course the oft-imagined cocktail parties. There’s a tender bit of business over her handbag and of course her depression: “an illness to which she wasn’t socially entitled.” Jeff Rawle’s Dad is bluffly affectionate, and Bennett’s afterlife frame neatly gets around the bald reality of his conversation. Furtive gropings in a cinema, day-trips to Morecambe, Bennett’s national service and visits to him at Oxford all come in for scrutiny, as Bennett unpacks the real writerly tragedy of what happens when your mum and dad don’t fuck you up, leaving you banal and well-adjusted, with less than your share of “dramas and disappointments”.

Gabrielle Lloyd (pictured left with Jeff Rawle) is all fragile hope and weathered acceptance as Mam, yielding some of Bennett’s finest comedic writing over her yearnings for those social symbols of avocado pears, artichokes, and of course the oft-imagined cocktail parties. There’s a tender bit of business over her handbag and of course her depression: “an illness to which she wasn’t socially entitled.” Jeff Rawle’s Dad is bluffly affectionate, and Bennett’s afterlife frame neatly gets around the bald reality of his conversation. Furtive gropings in a cinema, day-trips to Morecambe, Bennett’s national service and visits to him at Oxford all come in for scrutiny, as Bennett unpacks the real writerly tragedy of what happens when your mum and dad don’t fuck you up, leaving you banal and well-adjusted, with less than your share of “dramas and disappointments”.

Such banality has proved rich material indeed for Bennett over the years, and judging by the keen observations and cruelties of Cocktail Sticks hasn’t been exhausted yet. The pain and truth are so muddled in with the tea-and-cake, have-another-psalm English nostalgia that even as you flinch at one you find yourself swaddled in the flannel embrace of the other. It’s delicate, precision work, and no one does it better than Bennett.

rating

Buy

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Good Night, Oscar, Barbican review - sad story of a Hollywood great's meltdown, with a dazzling turn by Sean Hayes

Oscar Levant is an ideal subject to refresh the debate about media freedom

Good Night, Oscar, Barbican review - sad story of a Hollywood great's meltdown, with a dazzling turn by Sean Hayes

Oscar Levant is an ideal subject to refresh the debate about media freedom

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews - Monstering the Rocketman by Henry Naylor / Alex Berr

Tabloid excess in the 1980s; gallows humour in reflections on life and death

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews - Monstering the Rocketman by Henry Naylor / Alex Berr

Tabloid excess in the 1980s; gallows humour in reflections on life and death

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Lost Lear / Consumed

Twists in the tail bring revelations in two fine shows at the Traverse Theatre

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Lost Lear / Consumed

Twists in the tail bring revelations in two fine shows at the Traverse Theatre

Make It Happen, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tutting at naughtiness

James Graham's dazzling comedy-drama on the rise and fall of RBS fails to snarl

Make It Happen, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tutting at naughtiness

James Graham's dazzling comedy-drama on the rise and fall of RBS fails to snarl

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: I'm Ready To Talk Now / RIFT

An intimate one-to-one encounter and an examination of brotherly love at the Traverse Theatre

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: I'm Ready To Talk Now / RIFT

An intimate one-to-one encounter and an examination of brotherly love at the Traverse Theatre

Top Hat, Chichester Festival Theatre review - top spectacle but book tails off

Glitz and glamour in revived dance show based on Fred and Ginger's movie

Top Hat, Chichester Festival Theatre review - top spectacle but book tails off

Glitz and glamour in revived dance show based on Fred and Ginger's movie

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Alright Sunshine / K Mak at the Planetarium / PAINKILLERS

Three early Fringe theatre shows offer blissed-out beats, identity questions and powerful drama

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Alright Sunshine / K Mak at the Planetarium / PAINKILLERS

Three early Fringe theatre shows offer blissed-out beats, identity questions and powerful drama

The Daughter of Time, Charing Cross Theatre review - unfocused version of novel that cleared Richard III

The writer did impressive research but shouldn't have fleshed out Josephine Tey’s story

The Daughter of Time, Charing Cross Theatre review - unfocused version of novel that cleared Richard III

The writer did impressive research but shouldn't have fleshed out Josephine Tey’s story

Evita, London Palladium review - even more thrilling the second time round

Andrew Lloyd Webber's best musical gets a brave, biting makeover for the modern age

Evita, London Palladium review - even more thrilling the second time round

Andrew Lloyd Webber's best musical gets a brave, biting makeover for the modern age

Maiden Voyage, Southwark Playhouse review - new musical runs aground

Pleasant tunes well sung and a good story, but not a good show

Maiden Voyage, Southwark Playhouse review - new musical runs aground

Pleasant tunes well sung and a good story, but not a good show

The Winter's Tale, RSC, Stratford review - problem play proves problematic

Strong women have the last laugh, but the play's bizarre structure overwhelms everything

The Winter's Tale, RSC, Stratford review - problem play proves problematic

Strong women have the last laugh, but the play's bizarre structure overwhelms everything

Brixton Calling, Southwark Playhouse review - life-affirming entertainment, both then and now

Nostalgic, but the message is bang up to date

Brixton Calling, Southwark Playhouse review - life-affirming entertainment, both then and now

Nostalgic, but the message is bang up to date

Add comment