Rites: 3D, CBSO, Volkov, Royal Festival Hall | reviews, news & interviews

Rites: 3D, CBSO, Volkov, Royal Festival Hall

Rites: 3D, CBSO, Volkov, Royal Festival Hall

Digital ingenuity with Stravinsky's Rite of Spring isn't same as theatre artistry

Were the great Diaghilev alive today, surely he’d be working in the imaginative possibilities of electronic technology - this was the opinion given me by the arts panjandrum, the late Sir John Drummond. And given the developments of 3D, who knows? Would it be this manipulation of our perceptions that fascinated him? 3D is certainly everywhere in dance now, though the challenge is to leap the judgment of it as merely a gimmick. I reckon while Wim Wenders’ film Pina 3D achieved that, the version of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring by Klaus Obermaier doesn’t.

Part of the Southbank Centre’s Ether series of “cross-arts experimentation” and implied technological invention, Rites was making a return nearly four years after we first goggled at its fusion of live orchestra, live dancer and 3D camera animation, and I had exactly the same reservations about it this time as last time, if not even more marked. Technology develops quickly but artistry moves even faster, and what looked in 2007 like a pardonably excitable reacting by 3D camera armed with Photoshopping animation software now needs to be examined for something beyond its technological expertise - its extra metaphorical and theatrical meaning. To me, nothing added and something lost.

Part of the Southbank Centre’s Ether series of “cross-arts experimentation” and implied technological invention, Rites was making a return nearly four years after we first goggled at its fusion of live orchestra, live dancer and 3D camera animation, and I had exactly the same reservations about it this time as last time, if not even more marked. Technology develops quickly but artistry moves even faster, and what looked in 2007 like a pardonably excitable reacting by 3D camera armed with Photoshopping animation software now needs to be examined for something beyond its technological expertise - its extra metaphorical and theatrical meaning. To me, nothing added and something lost.

The format was the same as last time: the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra conducted by Ilan Volkov gave a three-part concert in itself, with Edgar Varèse’s amusing Tuning Up Sketch followed by György Ligeti’s woozy, outer-space Lontano - two pieces half a century old or more which successfully predict the kind of jokes and musical effects created by electronic keyboards and looped samples in this era. The entire concert has a curious right-hand left-hand quality - it celebrates the latest electronic technology, using music that long ago predicted and inquired, using the orchestra, into the kinds of musics that electronics recreate now.

The Varèse is a good joke, a 1947 sketch that reinvents the identical sounds of every orchestra tuning up, coloured with the snatches of quotes from familiar works that different instruments favour - the downward cascades of the flutes, pompous fanfares of trombones, all the sounds layered and patched together in deceptive casualness so that the actual tuning up that follows for the next piece becomes the punchline. You hardly realise it is a composition, until you see Volkov firmly conducting it.

Ligeti’s Lontano (1967) begins on the A flat, which sends your aural senses briefly hunting around after the insistent assertiveness of the A in the previous piece, a drifting cloudscape of sounds much as if they were electronic compositions for journeys into outer space. Faint woozy oscillations of tuning in the sustained soft unisons, almost imperceptible pianissimos, deep reverberations in the lower brass, these too test your ears. And the entire thing - especially given the contemporaneity with Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, which used Ligeti pieces again - enhances the niggling feeling that in the 21st century we have rather lost the plot, so far out of touch with previous generations’ comic-book inventiveness are we as we exclaim at our technological machines.

This spaceyness in the Ligeti makes a powerfully appropriate set-up for the visuals-added experience of Stravinsky’s 98-year-old Rite of Spring, where the visual conjuring is strongly tilted towards a sense of an individual's lostness in space. Obermaier’s theme is solipsistic: he doesn’t seem to consider the work’s associations with public rituals, crowd worship, the mass throwing out an individual to save themselves, the cruel scenario which has lent itself more than 100 times to choreographers since Nijinsky's original.

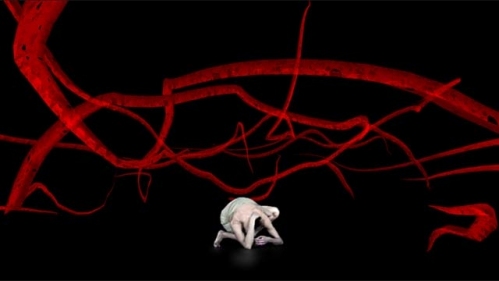

The CBSO fielded an enormous orchestra of some 100 players for this, but it’s the tendency of images to drag the audience’s attention away, fragment the concentration, and Obermaier’s device is highly attention-seeking. In the right-hand corner of the stage is a platform for a lone dancer, the tall, leggy, short-haired blonde Julia Mach in a brief shift. As she moves she’s filmed by a 3D camera into software that manipulates her movements to gigantic effect on the screen overhead, which through 3D glasses gives you an illusion of being lost with her in the darkness on a narcotic hallucination trip, in which her hands seem to grab your face, or tiny images of her whirl through space like minute comets. A dancing grid for the floor heaves and bucks like the ocean, which she rides like a surfer, and the entire effect is at times quite discombobulating.

But after you've spent time marvelling, "How do they do that?" you see through it, the images riffing on one single story of a woman in a manipulated dream of floating. The layers of human emotions and fantasies that make The Rite of Spring so stimulating to choreographers aren't to be found here, nor does its technological image-making seem particularly strange today (time is even crueller to technology than it is to women). The visuals (created by Ars Electronica Futurelab) also seemed to me to have the negative effect of cooling down Volkov's handling of the orchestral score. He produced a virtuosic, clean account of this supersized score, absolutely in keeping with the clinical IT whizzery, but lacking enough of the threatening tension and almost animal suspense that the ballet calls for. This was the work that shattered classical music on its arrival - I can't help wondering whether Volkov felt that the electronic ballet upstairs on that screen required him to cut his orchestral cloth for it, to fit his soundscore to the visual theorems and computer software.

It worked in a woozy, trippy way for the central slow section where the digital artist sent tiny dots of light flying in the air like sparks from a bonfire, or stars in galaxies - all this mournful, Debussyan Impressionism and dancing fireflies. Less so, though, for the apprehensive first section and the pumping, inexorable third, where those animist spirits of Stravinsky's had been distanced by Obermaier’s nerdy insistence on focusing on Mach alone among her pixels. There’s a lot of guff on the programme note about 32 microphones that integrated the orchestra in the interactive process, the complex computer systems and immersive environments, but Obermaier is a clever techie basically, not so much of an imaginative artist.

Nothing underlines this more than when you glance at the dancer who is generating the screen’s tricks and see how dully and unenlighteningly her movements integrate in reality with Stravinsky’s music. This programme shows, if nowt else, that the composers heard and composed the future long ago, and created it with the limitless sonic possibilities of the symphony orchestra, assembling, layering, painting entirely new sounds - and the thrills of seeing technology catch up are limited. No doubt there are bolder visionaries out there in digital-land than Obermaier, but if it's 3D and Stravinsky's Rite you want, you can do no better than hasten to Pina 3D.

Watch a snatch from the digital Rite

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Classical CDs: Bells, birdsong and braggadocio

British contemporary music, percussive piano concertos and a talented baritone sings Mozart

Classical CDs: Bells, birdsong and braggadocio

British contemporary music, percussive piano concertos and a talented baritone sings Mozart

Siglo de Oro, Wigmore Hall review - electronic Lamentations and Trojan tragedy

Committed and intense performance of a newly-commissioned oratorio

Siglo de Oro, Wigmore Hall review - electronic Lamentations and Trojan tragedy

Committed and intense performance of a newly-commissioned oratorio

Alfred Brendel 1931-2025 - a personal tribute

A master of feeling and intellect

Alfred Brendel 1931-2025 - a personal tribute

A master of feeling and intellect

Aldeburgh Festival, Weekend 2 review - nine premieres, three young ensembles - and Allan Clayton

A solstice sunrise swim crowned the best of times at this phoenix of a festival

Aldeburgh Festival, Weekend 2 review - nine premieres, three young ensembles - and Allan Clayton

A solstice sunrise swim crowned the best of times at this phoenix of a festival

RNCM International Diploma Artists, BBC Philharmonic, MediaCity, Salford review - spotting stars of tomorrow

Cream of the graduate crop from Manchester's Music College show what they can do

RNCM International Diploma Artists, BBC Philharmonic, MediaCity, Salford review - spotting stars of tomorrow

Cream of the graduate crop from Manchester's Music College show what they can do

Classical CDs: Bells, whistles and bowing techniques

A great pianist's early recordings boxed up, plus classical string quartets, French piano trios and a big American symphony

Classical CDs: Bells, whistles and bowing techniques

A great pianist's early recordings boxed up, plus classical string quartets, French piano trios and a big American symphony

Monteverdi Choir, English Baroque Soloists, Suzuki, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - the perfect temperature for Bach

A dream cantata date for Japanese maestro and local supergroup

Monteverdi Choir, English Baroque Soloists, Suzuki, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - the perfect temperature for Bach

A dream cantata date for Japanese maestro and local supergroup

Aldeburgh Festival, Weekend 1 review - dance to the music of time

From Chekhovian opera to supernatural ballads, past passions return to life by the sea

Aldeburgh Festival, Weekend 1 review - dance to the music of time

From Chekhovian opera to supernatural ballads, past passions return to life by the sea

Dandy, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - a destination attained

A powerful experience endorses Storgårds’ continued relationship with the orchestra

Dandy, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - a destination attained

A powerful experience endorses Storgårds’ continued relationship with the orchestra

Hespèrion XXI, Savall, QEH review - an evening filled with laughter and light

An exhilarating exploration of innovation in 16th and 17th century repertoire

Hespèrion XXI, Savall, QEH review - an evening filled with laughter and light

An exhilarating exploration of innovation in 16th and 17th century repertoire

Add comment