Eadweard Muybridge, Tate Britain | reviews, news & interviews

Eadweard Muybridge, Tate Britain

Eadweard Muybridge, Tate Britain

Trotting horses were only a small part of a fascinating story

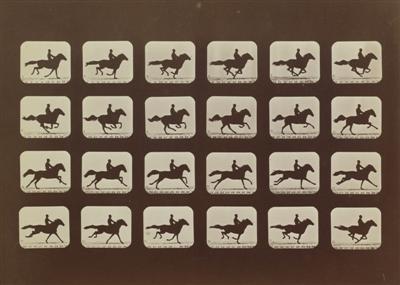

Multiple images of silhouetted horses cantering against blank backgrounds in grids of movement are what most people associate with Eadward Muybridge. Made in the late 1880s, they have contributed to his lasting reputation as a pioneer of photography and the moving image. So it is astonishing to discover through Tate Britain’s magnificent exhibition of his life’s work, that horses were only part of a story packed with surprises.

The show’s chronological arrangement is designed to build curiosity: you enter a horse-free zone and have to wait for the horses. But you become immediately immersed amongst scenes set in the epic mountains and lakes of California’s Yosemite National Park, the very place where Muybridge's acquaintance, Ansel Adams, later made his mark.

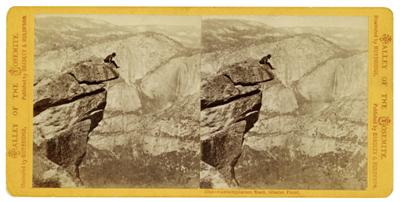

Reliant on natural light, the prints are romantic and heroic – as befitted that pioneering late 19th century. To achieve them, he (and his trusty team) hauled a massive large format camera and 17 x 22-inch glass plate negatives up perilous paths in his search for perfect views. We read that he culled "scores" of trees standing in the way, and we benefit from the clear sightlines achieved. Sculptural rock formations and views straight from Caspar David Friedrich paintings fascinated him, and he climbed high to capture outlines and forms epitomised by the delicately printed Contemplation Rock, Glacier Point, 1972 (pictured below right). A local artist squatting on the edge (apparently contemplating his future suicide), sees the Rock outlined against what resembles a vast, painted backdrop to an early cinema drama.

For the lakes and waterfalls, he opened his lens to long exposures, a process which turns clear water milky and in Pi-Wi-Ach, Vallery of Yosemite (Shower of Stars) Vernal Fall converts a waterfall into an incongruously abstract stripe of blazing white light. The most creative work was done in Muybridge’s "Flying Studio," a tent which we see contains neatly arranged bottles of chemicals and associated paraphernalia. The quality of printing he achieved there is astonishing for its tonal ranges and absolute clarity, and depth of field. But he was also experimenting in proto-Photoshop trickery - sharing a cloud formation with two scenes by printing double images and making different exposures across the same negative. On other travels, he documented the lives of the indigenous people, living amongst them like a modern reportage photographer, to create a 'realistic' impression instead of stereotypes.

For the lakes and waterfalls, he opened his lens to long exposures, a process which turns clear water milky and in Pi-Wi-Ach, Vallery of Yosemite (Shower of Stars) Vernal Fall converts a waterfall into an incongruously abstract stripe of blazing white light. The most creative work was done in Muybridge’s "Flying Studio," a tent which we see contains neatly arranged bottles of chemicals and associated paraphernalia. The quality of printing he achieved there is astonishing for its tonal ranges and absolute clarity, and depth of field. But he was also experimenting in proto-Photoshop trickery - sharing a cloud formation with two scenes by printing double images and making different exposures across the same negative. On other travels, he documented the lives of the indigenous people, living amongst them like a modern reportage photographer, to create a 'realistic' impression instead of stereotypes.

Though born in Kingston-on-Thames, London (in 1839), Muybridge lived most of his life in San Francisco, and in later years returned frequently to Europe, especially London, to give talks and demonstrations of his inventions. He died in Kingston in 1904, leaving a legacy as much as an engineer, technician, experimental scientist and inventor, as a photographic artist. Articles illustrating his images of animals in motion appeared in the Scientific American not Art magazines. But as this exhibition proves, the landscapes, the striding animals, lyrical women dancing, and nude men posing in positions imitated by classical Greek sculptors, are undeniably the work of an artist.

Also highlighted here is the soft-eyed, intense and woolly bearded photographer’s gift for marketing and self-promotion. Muybridge was a Brand; he sold the early landscape prints under the appropriate trading title of Helios, the sun god, for $20 a pop. And while living briefly in Guatemala to escape a dropped murder charge for shooting his wife’s lover – another surprise revelation - he made romanticised documentary photographs of the workers harvesting the coffee and sold them to local companies for their ads to promote it abroad.

Back in San Francisco where he spent most of his life, in 1877, Muybridge documented the new buildings and the city's changing profile in two meticulously produced, epic panoramics. Composed from a freize of 11 and 16 panels, all perfectly, seamlessly matched, they are a masterpiece of craft and artistry, and significant historical documents of the time. His friend and patron, the railway magnate Leland Stanford played a vital part in Muybridge's life. We see his sumptuous mansion and interior décor in large, detailed photographs, but it was the millionaire’s horses which drew them closest. A profile portrait of Standford's son riding a pony, marks the beginning of the legendary experiments on motion.

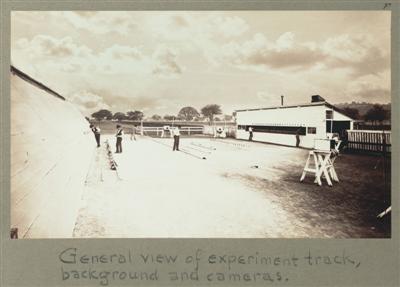

The progression of the classic horse-in-motion shots (pictured right) unfolds slowly. A photograph titled in his own hand, General view of Experiment track, background and cameras, Plate F (1881) (pictured below), reveals the background to the classic moving horse silhouettes. The clevely constructed set bears a strikingly resemblance to a shooting (guns) gallery. Lime laid on a short running track and a white backdrop served as reflectors and the low gallery facing the white wall, is punctuated by rectangular windows through which peer a bank of 12 to 24 camera lenses.

The progression of the classic horse-in-motion shots (pictured right) unfolds slowly. A photograph titled in his own hand, General view of Experiment track, background and cameras, Plate F (1881) (pictured below), reveals the background to the classic moving horse silhouettes. The clevely constructed set bears a strikingly resemblance to a shooting (guns) gallery. Lime laid on a short running track and a white backdrop served as reflectors and the low gallery facing the white wall, is punctuated by rectangular windows through which peer a bank of 12 to 24 camera lenses.

A trip wire triggers the shutters as the horse runs past. The resulting images are printed as small, stamp-sized rectangles on sheets resembling contact prints, and positioned in sequence, they simulate the motion - thus solving the mystery of how many horse’s legs leave the ground at a time.

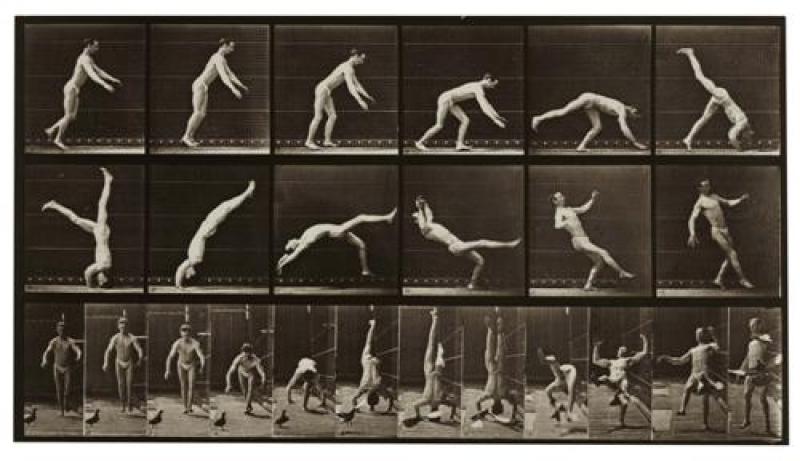

We move from horses to other animals (including a seemingly static buffalo and a disobedient dog), and to cinematically directed scenarios involving men and women – mostly naked until the Victorian moralists intervened and shorts, dresses and hats appear. Most beautiful is the naked model, Catherine Aimer - smoking in a chair, dancing in abandon and flaunting the sensual pleasure of nudity. Another wafts around in a floaty dress pre-dating Isadora Duncan. The men’s classic poses, somersaults, wrestling and boxing moves, are endlessly homoerotic and were greedily collected (with many others in these series) by Francis Bacon as models for his own portraits. All were produced in a small stage-set using six cameras arced around the subjects.

We move from horses to other animals (including a seemingly static buffalo and a disobedient dog), and to cinematically directed scenarios involving men and women – mostly naked until the Victorian moralists intervened and shorts, dresses and hats appear. Most beautiful is the naked model, Catherine Aimer - smoking in a chair, dancing in abandon and flaunting the sensual pleasure of nudity. Another wafts around in a floaty dress pre-dating Isadora Duncan. The men’s classic poses, somersaults, wrestling and boxing moves, are endlessly homoerotic and were greedily collected (with many others in these series) by Francis Bacon as models for his own portraits. All were produced in a small stage-set using six cameras arced around the subjects.

The final major section focusses on the 1879 invention of a Zoopraxiscope, the instrument which brought ‘moving’ imagery closest to cinema. Projected onto a wall, a circle of horses trot as if on a treadmill, and a couple dance ceaselessly, their images created by tracing small prints then painting them on to a disc which animates them as it spins and induces a hypnotic, fairground-like effect.

Muybridge’s influence has passed through layers of generations of photographers, artists and film-makers. But none so obviously or so remarkably re-interpreted as those photographs collected and studied by Francis Bacon. A room in the Francis Bacon Collection at Dublin’s Hugh Lane Gallery is lined with framed loose pages – copiously annotated, torn and splodged with paint - taken from Muybridge's classic books Animal Locomotion and Animals in Motion. His collecction of five copies of The Human Figure in Motion, are reminders of their overwhelming influence on his sculpturally tangled, three-dimensional figures.

The exhibition closes on a small bronze by Degas, Horse clearing an Obstacle, 1887-8. While its legs and hooves are poised in perfect cantering positions, the overall form is surprisingly less elegant than those flat photographs of the real thing. In between Muybridge, Degas and late 20th century developments, there lodges the American scientific explorer-cum-photographer, Harold Edgerton who worked at MIT in Chicago. Edgerton achieved extraordinary, equally beautiful results with his invented stroboscopic lighting and ultra-high-speed flashes. Instead of studying animals in motion, he used speeds of up to a millionth of a second, to freeze movements invisible to the human eye - flying tennis balls, descending divers, a bullet cutting through an apple, and the best-known Milk Drop Coronet.

I left this stunning exhibition awed by the extent of Muybridge’s work - and suddenly aware of where and how I was placing my feet and legs.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Bogancloch review - every frame a work of art

Living off grid might be the meaning of happiness

Bogancloch review - every frame a work of art

Living off grid might be the meaning of happiness

Do Ho Suh: Walk the House, Tate Modern review - memories are made of this

Home sweet home preserved as exquisite replicas

Do Ho Suh: Walk the House, Tate Modern review - memories are made of this

Home sweet home preserved as exquisite replicas

Comments

...