Sue Steward 1946-2017: She came, she saw, she salsa'd | reviews, news & interviews

Sue Steward 1946-2017: She came, she saw, she salsa'd

Sue Steward 1946-2017: She came, she saw, she salsa'd

The Arts Desk's adventurous music and photography critic remembered

Sue Steward, who died suddenly last week from a brain haemorrhage, was one of theartsdesk’s most loved members, her free spirit and her double specialism in world music and photography making her an intrinsic asset to this pioneering critics’ site in 2009. Her unfussy eye for colour and composition also influenced the early design of The Arts Desk and traces remain today.

With her talent for friendship she naturally drew other new music explorers into her circle of enthusiasm, as well as the photographers whose work she wrote about and curated with lilting sympathy. She made friends wherever she worked, from her PR days with Richard Branson and Malcolm McLaren, to the indie music magazines such as Collusion, which she founded, and Songlines to the mainstream outlets such as the Daily Telegraph, The Observer and BBC Radio 2.

Her colleagues here on theartsdesk, including writers Peter Culshaw, Mark Hudson and Mark Kidel, and photographer Jillian Edelstein, remember Sue's unaffected and infectious spirit.

Sue Steward, writer, broadcaster, author, magazine founder, exhibition curator, DJ, picture editor, 19 September 1946–23 August 2017

She never just walked through a door, but hurtled, a whirlwind of nervous, sometimes chaotic enthusiasm and energy

Sue Steward was someone who ran, literally, through her life and work. Having lived in the next room to Sue for four years in a shambolic north London flat, I can attest to the fact that she never just walked through a door, but hurtled, a whirlwind of nervous, sometimes chaotic enthusiasm and energy, forever on the run to the next meeting, gig or launch.

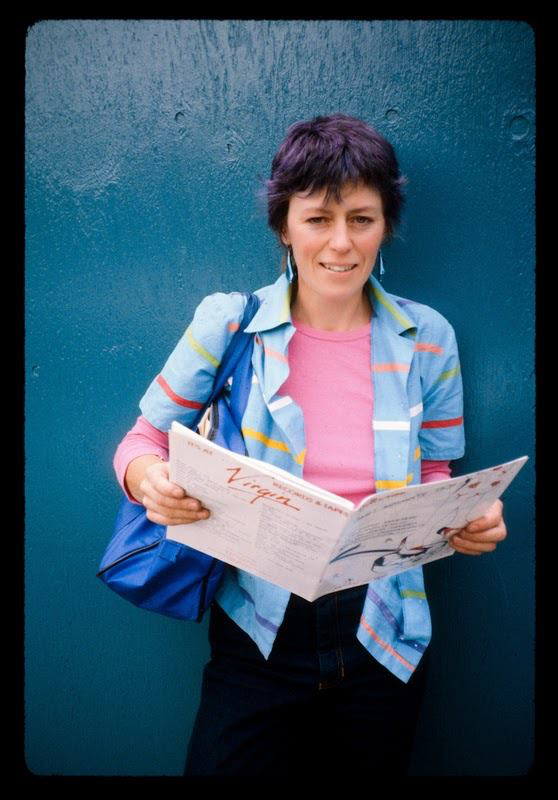

When I first met her in 1981, Sue was working as a picture researcher in medical publishing by day, while writing for the just-launched radical listings mag City Limits, co-editing the avant-garde music magazine Collusion, which she’d co-founded with her then-boyfriend, musician and writer David Toop, and others while putting together a multi-authored women’s history of women in pop music, a utopian project convened in marathon meetings round our kitchen table. (Pictured below, Sue in 1981, photo by Kevin Laffey)

The other contributors gradually dropped out and the book was eventually published in a more scaled-down form as Signed, Sealed and Delivered: True Life Stories of Women in Pop, with only Sue and Sheryl Garratt credited as authors. It says something about the state of the times that the book still seemed radically novel in 1984.

The other contributors gradually dropped out and the book was eventually published in a more scaled-down form as Signed, Sealed and Delivered: True Life Stories of Women in Pop, with only Sue and Sheryl Garratt credited as authors. It says something about the state of the times that the book still seemed radically novel in 1984.

Collusion, meanwhile, was a quirkily eclectic compendium of the trashy, the elevated and the resolutely marginal. Falling very much into the latter category were some of the first tentative writings on what would later become known as “world music” – an area in which Sue made an important but under-acknowledged contribution. She could already see that sounds which then seemed mindbogglingly recondite and worthily “ethnic”, from Egyptian belly-dance rhythms to salsa and Indian film music, could be viewed in a more radical light.

If it was Toop, I understand, who first prompted this interest, Sue soon surpassed him in knowledge and passion, forming consecutive obsessions with Nigerian juju-maestro King Sunny Ade – with whom she was infatuated from a distance – and Afro-Cuban diva Celia Cruz – with whom she later formed a strong friendship.

Yet Sue’s self-reinvention as one of only two or three journalists specialising in this gradually burgeoning and still un-named scene was often traumatic. She was, initially at least, an unconfident writer, and every new piece put her and her editors – and sometimes flatmates – through agonies of indecision. But she honed her craft, with her interests and knowledge careering into fabulous new areas of sound and rhythm against a turbulent early Eighties backdrop of rapidly entrenching Thatcherism, embattled sexual politics, critical theory, the rise and fall of the Livingstone GLC and the miners’ strike. For Sue her musical explorations weren’t a mere frivolous add-on, but central to the struggles of the time: what could be more politically significant than shaking the Western listener out of their complacent cultural rut?

A corn-merchant’s daughter from Melton Mowbray in Leicestershire, Sue studied sciences and became a biology teacher in Liverpool before running away to London to get involved in the music business in any way she could: working in the mail-order department at the newly created Virgin Records, and later minding the Sex Pistols for Malcolm McLaren, while sampling everything the metropolis could throw at her.

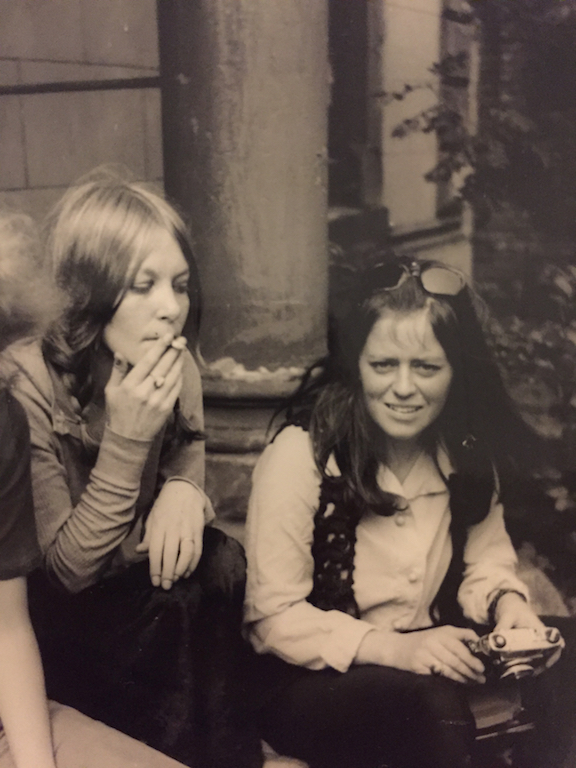

She was in many ways an archetypal woman of her times, who reads at first sight like a character from some Swinging London morality fiction: the kind of provincial party girl who invades the big city, then gets punished for her free spirit, brought to heel through a succession of wildly inappropriate relationships. (Pictured left, Sue with her best friend Jude Madden, courtesy Caroline Madden.)

She was in many ways an archetypal woman of her times, who reads at first sight like a character from some Swinging London morality fiction: the kind of provincial party girl who invades the big city, then gets punished for her free spirit, brought to heel through a succession of wildly inappropriate relationships. (Pictured left, Sue with her best friend Jude Madden, courtesy Caroline Madden.)

Sue, however, turned the stereotype around, transcending the influence of various male partner-teacher figures, including Fred Frith of Henry Cow and Toop, while fighting her way through to become a significant figure in her own right. If Sue never made great claims for her role in creating the world music phenomenon (whose commercialisation and ultimate degradation she regarded with some bemusement), it was partly because she lacked the necessary confidence – and pomposity! – but mainly because she’d moved on to new interests, as art critic, proponent of “outsider art” and esteemed photography curator.

There was something endearingly childlike about Sue. When I first met her I was little more than a child myself. She was a decade older, but seemed little different. From my observation, and I only saw her a couple of times in her final years, she managed to keep that youthful fire burning.

I remember her sheer enthusiasm for finding great music and her desire to share it with others

I ran into Sue intermittently from the 1980s. I was impressed by the epic eclecticism of the wonderful Collusion magazine she co-founded in the early part of that decade – one issue that I have includes articles about African pop in New York, the story of Hawaiian guitar, Walt Disney’s early music and the erotic pleasures of assorted dance crazes. This was amazing for me, and even liberating, as the majority of music journalists at the time were in a narrow bubble of the latest dull white indie shoe-gazers.

Back then, pre-internet, music had to be sought out, and Sue would be among the keenest hunters, finding gems in bargain bins or Stern’s African music shop – there was a relatively small community of “world music” fanatics who would swap information. I think I’m right that she found some early hip-hop in New York which she gave to her pal David Toop (he ended up writing the first book on hip-hop, The Rap Attack), and he turned her on to the Fania All-Stars which contributed to her enduring love of salsa and her definitive book on the genre, Salsa: Musical Heartbeat of Latin America.

What I remember was her sheer enthusiasm for finding great music and desire to share it with others. She would broadcast, illegally if necessary, on private stations like K-Jazz and DJ at the Mambo Inn which she helped to set up in Brixton. We would be among the very few non-Latinos at those wonderful series of long-lost Sunday night Latin concerts in Leicester Square. I occasionally ran into her farther afield, both of us coinciding in Havana in 1997, knocking back cocktails and swapping tips of who to see and gossiping about colleagues. (Pictured below, Sue with Daily Telegraph colleagues Caspar Llewellyn-Smith, Marc Lee, Hilary Lloyd and David Johnson in 1995, picture courtesy David Johnson)

She had a Zelig-like ability to be where the action was, including being employed by our mutual friend Malcolm McLaren in the year of punk. She became an authority on photography, which I couldn't follow her into and relocated to the south coast, and our paths crossed much less often.

She had a Zelig-like ability to be where the action was, including being employed by our mutual friend Malcolm McLaren in the year of punk. She became an authority on photography, which I couldn't follow her into and relocated to the south coast, and our paths crossed much less often.

When I became the original New Music editor when theartsdesk was set up in 2009, I was thrilled to get her involved and she produced some typically brilliant, well-informed, amusing copy from WOMAD or wherever. Astonishingly and sadly, as this is an obituary, one of her finest skills was as an obit writer, the most moving being on photographing her dead mother.

But obits were one way for her to celebrate artists she loved - she wrote terrific ones for theartsdesk including on Captain Beefheart and the great Colombian salsero Joe Arroyo (the best of those Sunday evening gigs). I was just rereading and marvelling at her Edmundo Ros obit for the Guardian. One of the impressive things about Sue was a lack of snobbery which afflicts most music journalists. She quoted gleefully a Melody Maker headline on Ros in 1939: “He came… he saw… he conga’d!”

Sue Steward – she came… she saw… she salsa’d! It was great to know you, Sue.

For us photographers she was a champion, looking out for us always, blowing our trumpets for us

I was going through my emails to see what communication I can find between Sue and me in the last while. One is from Sue on 26 February 2016 thanking me for a lovely afternoon, “…including the biscuits,” she remarks.

We must have discussed her move to Hastings, since I wish her luck in an ensuing email, and she comments on the book that I am now crowdfunding on Unbound publishers: “I shall keep thinking of ideas for you for a gallery. It would be such a waste to not let that terrific book be published... and the exhibition to coincide with it!”

It’s the belief, the affirmation and the encouragement from critics, writers and observers like Sue in the field of arts, and particularly in the field of photography, that spur us on, as the work is often created alone and in a solo vacuum. And that was Sue – for us photographers she was a champion. Looking out for us always, blowing our trumpets for us and imparting her excitement at the discovery of new work to the wider world in the several publications she worked for as a freelancer.

She interviewed me for theartsdesk in October 2009 about my Truth and Lies book of photographs documenting South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission proceedings. When I look back at it and I go over Sue’s questions, I see the rigorous attention to detail and her enthusiasm for all matters related to photography. I copied out the questions she put to me as she was going through my career.

She started with: “Would it be accurate to describe your work in definable thematic chunks?” “Definable thematic chunks” is so evocative. Elsewhere during the interview she is challenging, sensitive, gently suggestive and remarkably insightful.

“So when did you get out into the wider world?” “Did anyone refuse to be photographed or create problems for you?”

“Did the magazine portraits which you became known for in this country serve as some kind of light relief in between the Truth and Lies sessions?” "... in the very different situation where you were photographing people for Truth and Lies - you needed to find some way to connect with them, quickly...”

“If you had shot the Truth and Lies portraits in colour, would their impact be as strong?”

“Your latest project Sangoma is about traditional South African healers, shamans who are the link with the ancestors. The word reminds me of Miriam Makeba’s autobiography which she named for her sangoma mother...?”

Such acute, knowledgeable questions. Sue’s support, her kindness, that warm, sparkly sweet smile, her laugh, and her genuineness will be sorely missed.

She had a quality of innocence and fun that was utterly contagious

I last saw Sue in St Leonards, where she’d moved after several years in Brighton, which she told me she’d never really liked. Sue was happy with her choice and fitted well into the hard-drinking, bohemian crowd that’s been drawn to “St Len’s” and Hastings over the years.

She hadn’t yet entirely unpacked, and many boxes of vinyl and books filled the rooms of her delightful small house. Much of her vinyl had gone, as she was short of cash. There was regret in her voice as she talked of the salsa albums that had gone to a dealer in Bath.

I remembered a day in the early 1990s, in New York where, when she was researching her salsa book, she’d taken me to a small specialist store somewhere in the labyrinth of the Grand Central Terminal subway station. She picked out classics for me – still a Latin American music neophyte – from the Fania All Stars, Willie Colon, Eddie Palmieri, Papaito and various Haitian bands I was then on the verge of discovering.

Even when she was visited by the black dog (I imagine those long email silences from her quarter may have been caused by a dive into a more introvert and troubled inner life), Sue could be full of burning curiosity and enthusiasm. Until this year, we met every year at WOMAD, pacing around the site, bumping into other world music old-timers and sampling the wide range of music on offer, texting each other ecstatically if we heard anything special that the other might be missing.

Sue was a very sharp dresser: never a slave to fashion, but with a keen eye for great fabric or colour combinations. She dressed without affectation, but expressing herself in a quiet but always beautiful way. Her refined visual sense proved to be an asset when she threw herself into outsider art, vodun paintings and sculpture from Haiti, and, perhaps most importantly, photography.

We had plans for a celebration of the great jazz photographer Val Wilmer, whom she had known for a very long time. Sue was never short of energy for new projects, always driven by the strength of an idea or the qualities of other people’s work, rather than ego or her own career advancement. She had a quality of innocence and fun that was utterly contagious: she will be sorely missed by all those that were lucky to have known or worked with her.

From a nervous and always self-deprecating start, Sue grew into a true and original writer as she did more and more journalism ignited by the adventurous content of her life and nuanced by her own exceptional sensitivity.

She wrote poignantly but drolly in the Telegraph ("Sid and Nancy: the Habitat years", 5 June 2008) about the time she found herself minding Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen in 1977: "I became maternally protective towards Sid and Nancy's relationship. They would sprawl on the sofa entangled like kittens, Nancy a voluptuous, gothic, porn-movie starlet and Sid a giant teddy boy."

An exquisitely tender article in the Observer ("All about my mother", 15 February 2009) about photographing her mother after death touched many hearts and drew dozens of empathetic reactions on social media. (Pictured right, Sue Steward and her mother.)

An exquisitely tender article in the Observer ("All about my mother", 15 February 2009) about photographing her mother after death touched many hearts and drew dozens of empathetic reactions on social media. (Pictured right, Sue Steward and her mother.)

Her many articles on theartsdesk ranged unexpectedly between music and photography, new and old, Gilberto Gil, Snowboy, Wolfgang Tillmans, Captain Beefheart lying down with Edward Weston, Irving Penn and Eadweard Muybridge. She also drew the public's eyes to catch exhibitions that might elude mainstream coverage: a brief show of the extraordinary music photographer Peter Williams inspired a compelling piece in which her passions for music and photography brilliantly combined; and she was as enthusiastic about finding exhibitions in Nottingham, Herefordshire and Swansea as in the Tate or the Photographers' Gallery.

Sue's compassionate curiosity about where music and imagery come from, the place of imagination and conscience in artists' creativity, and her infectious pleasure that what we see and hear can so much enhance our lives, defined her as one of the most honest of journalists and most lovable of human beings.

- A photography book sale that Sue had organised is to take place next weekend, 2-3 September, in St Leonard's, East Sussex: details here

Buy

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

When I started writing about

Beautiful!

How awful, terrible shock to

Truly bowled over by the most

At one point Sue and I worked

I am absolutely moved by the

It has been wonderful to read