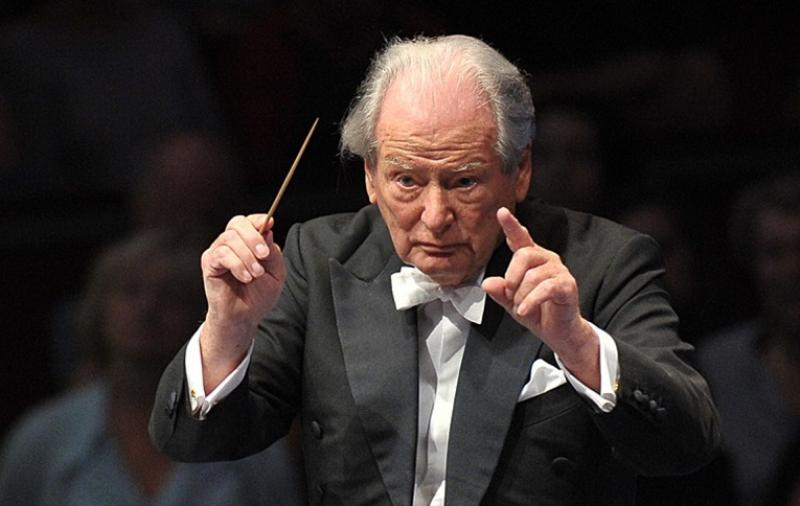

Interview: Sir Neville Marriner and the I, Culture Orchestra | reviews, news & interviews

Interview: Sir Neville Marriner and the I, Culture Orchestra

Interview: Sir Neville Marriner and the I, Culture Orchestra

The conductor has died aged 92. We revisit an interview from 2011 when his energy remained undimmed

We’re in Gdańsk for the launch of the I, Culture Orchestra (sounds like an Apple product, someone points out). The new outfit has Sir Neville Marriner as guest conductor, at 87, still on sparkling form. The orchestra has brought together young musicians from across Eastern Europe “to encourage better cultural understanding” between Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan.

The orchestra’s birth is a cultural initiative marking Poland's presidency of the European Union. Unlike in this country where arts funding is being cut, the project represents Poland’s belief in the importance of the arts – last year’s Polska Year had a budget of about four million euros which was spent putting on events throughout the UK (their research said it was money well spent, that people’s image of Poland changed for the better, and more businesses and tourists will be attracted to the country).

The orchestra’s birth is a cultural initiative marking Poland's presidency of the European Union. Unlike in this country where arts funding is being cut, the project represents Poland’s belief in the importance of the arts – last year’s Polska Year had a budget of about four million euros which was spent putting on events throughout the UK (their research said it was money well spent, that people’s image of Poland changed for the better, and more businesses and tourists will be attracted to the country).

The I, Culture project will set them back another million or so. It is paid for by the privately funded Adam Mickiewicz Institute, so it isn’t European tax payers’ money going down the tubes for an artistic experiment. There is also a decidedly political subtext.

There’s no doubting the orchestra’s amazing verve and enthusiasm, even if understandably they were a little rough around the edges

The orchestra is one attempt by the Poles to put down a marker as a leader of Eastern Europe, and not just culturally. The orchestra is notably independent from Russia and Germany, Poland’s old enemies and countries that have historically had a higher prestige culturally. Even the launch in Gdańsk has political resonance as it was where Solidarnosc and Lech Walesa sowed the seeds of the end of the communist empire in the shipyards (we are taken round the impressive museum dedicated to those epochal events). A paradox here is that the residual high standards of young classical musicians is largely due to the Soviet-era classical education system, which produced so many of the great instrumentalists of the last century.

If there are no Russians in the band (pictured right), the repertoire does feature mainly Russian music such as Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony and Shostakovich’s Fifth, with a big chunk of Polish composer Szymanowski, performed by some of the top young musicians from the assorted countries of Eastern Europe. There’s no doubting the orchestra’s amazing verve and enthusiasm, even if understandably they were, when I saw them in early rehearsal, a little rough around the edges. Whether they deliver in performance we will have to wait and see till this Sunday, when they play the Royal Festival Hall. They are on tour in Western Europe, and plan to tour Eastern Europe in 2012.

If there are no Russians in the band (pictured right), the repertoire does feature mainly Russian music such as Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony and Shostakovich’s Fifth, with a big chunk of Polish composer Szymanowski, performed by some of the top young musicians from the assorted countries of Eastern Europe. There’s no doubting the orchestra’s amazing verve and enthusiasm, even if understandably they were, when I saw them in early rehearsal, a little rough around the edges. Whether they deliver in performance we will have to wait and see till this Sunday, when they play the Royal Festival Hall. They are on tour in Western Europe, and plan to tour Eastern Europe in 2012.

After one rehearsal I asked Sir Neville Marriner about his previous visits to Poland. He said that the Academy of St Martin in the Fields, the chamber orchestra which he founded in 1959, had been invited in the late Seventies. “Before we even played a note, they gave us a 10-minute standing ovation. Anything from the West was enormously welcome at the time. We used to try and help out the Polish orchestras by sending them music they needed.”

So what made him accept a new project like I, Culture? He says he was partly following in the footsteps of Daniel Barenboim and his West-Eastern Divan Orchestra. Some of the countries like Azerbaijan and Armenia have long-running enmities and it was a symbolic gesture of peace.

More than that, the experience would be a powerful one for the young people involved, being able to play in such prestigious places as the Festival Hall. “When I first played the Carnegie Hall, there’s a wave of history there, all the people that have played before you. When you have done it, it’s a remarkable part of your life. Even for those who decide not to be musicians. Compared to the States, where young musicians of talent are more easily picked up, in Eastern Europe there are fantastic musicians who are under the radar.” As well the soloists, the Polish violinist Agata Szymczewska and the Swedish born pianist (Polish father, though) Peter Jablonski, there are numerous impressive musicians from deeper in the East. One example of several I met with stellar potential being Natia Mdinaradze, a hugely talented violinist from Tblisi in Georgia.

Marriner thinks: “Music education is pathetically neglected in this country [the UK] at the moment. My son (Andrew Marriner, principal clarinet of the LSO) got a good music education, but he went to a posh school. You have to pay for it.”

He says these days he gets numerous offers he would have “bitten [his] arm off“ for when he was younger, but now he’s selective. Some of them don’t work – a project to start an Athens Orchestra was a disaster. Marriner made plans for a couple of years of concerts but the main sponsor kept suggesting changing the programme for his favourites, with the threat of pulling the plug, among other problems.

I asked Heifetz what her name was so I could introduce her. He said, 'I don’t know, I rented her'

As far as arts funding goes, he comments that the Academy of St Martin-in-the-Fields only got any sponsorship after 50 years, from Siemens. When he wanted to take them to Buenos Aires he was turned down by John Cruft, “a very bad oboe player who became the boss of the British Council” (and later the Arts Council – he had hired Marriner for the LSO in 1946, so the full story is likely to be more complex).

Having no funding, the Academy relied on the income from recordings. “I was miffed about being turned down, and also bloody-minded,” he says. This is likely to have somewhat damaged Marriner’s reputation in the long-term. They recorded over 800 albums, many brilliant but quite a few mediocre, and became ubiquitous, notably in the States (one New Yorker cartoon had a couple of parrots, one saying, “That was the Academy of St-Martin-in-the-Fields,” while the other one chirps “…conducted by Sir Neville Marriner”).

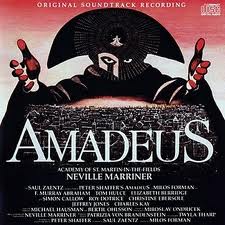

Their biggest hit, which sold over a million, was the soundtrack to the film Amadeus, which was recorded before Milos Forman started filming. “At the beginning, Milos knew nothing about Mozart, by the end he was the world’s leading expert,” says Marriner with an avuncular twinkle. He's now retired from being Music Director of the Academy, and has passed the baton over to violin superstar Joshua Bell. He remains, though, Life President and is still actively involved.

Their biggest hit, which sold over a million, was the soundtrack to the film Amadeus, which was recorded before Milos Forman started filming. “At the beginning, Milos knew nothing about Mozart, by the end he was the world’s leading expert,” says Marriner with an avuncular twinkle. He's now retired from being Music Director of the Academy, and has passed the baton over to violin superstar Joshua Bell. He remains, though, Life President and is still actively involved.

Marriner's reputation in the States helped him become the first music director of the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra from 1969 to 1978. One reason he looked forward to taking the job was to meet his hero, the great Jascha Heifetz. (Not everyone loved his music; Virgil Thomson found it cold and called Heifetz’s style of playing "silk-underwear music", a term he did not intend as a compliment.)

Marriner befriended Heifetz, sometimes playing table tennis with him, but he was “the saddest man I ever met. He had no friends really; he seemed to be incapable of comfortable relationships. He arrived at a party I gave with a wonderful dishy girl when we lived in Beverley hills. I asked him what her name was so I could introduce her. He said, 'I don’t know, I rented her'”.

So if it came to the proverbial desert island, what recordings of his would he take? “I tell you something, if I never hear Vivaldi’s Four Seasons ever again, I won’t mind a bit.” He says he has a particular soft spot for his version of Richard Strauss' Metamorphosen. At 87, he still has numerous projects on the go. The week after I meet him, he is conducting Britten’s War Requiem in Brussels. He thinks he fancies another go at some of the less famous Mozart operas.

Unlike Heifetz, he is full of joie de vivre and is a good advertisement for the fabled longevity of conductors. Instrumentalists, I say, often are more miserable. “That’s because they are always guilty. They feel they should be practising more. And unless you are absolutely fluent, you are going to be frustrated. Whereas the conductor only has to worry about the music, and he uses the orchestra as an instrument to be tuned.”

Sir Neville Marriner, 1924-2016

Buy

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

Add comment