The Surreal House, Barbican Art Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

The Surreal House, Barbican Art Gallery

The Surreal House, Barbican Art Gallery

Images that trouble and dazzle: as satisfying as a trip round Duchamp’s brain

Surrealism, it occurred to me while looking round this fine exhibition, is like pornography: it is hard to define, but everyone knows it when they see it.

The early Surrealists, led by André Breton, were deeply influenced by Freud. Freud saw the house as a symbol for the body, and thus, as with bodies, by definition an object that is subject to decay, to ultimate disintegration. Perhaps even more influential was the German word for the uncanny – unheimlich, un-home-like. Houses seem to define our sense of place, and so it is a brilliantly conceived stroke to begin the exhibition with two iconic pieces of house-less-ness: Buster Keaton in Steamboat Bill Jr, desperately trying to escape a hurricane, and time after time having his house physically disappear; and Marcel Duchamp’s Fresh Widow (1920, pictured right), his alter-ego Rhose Sélavy’s first work (right), in which the glass, the function and purpose of windows, is replaced by shiny black leather – the elements of sexuality, of skin and therefore of danger, make the usually transparent window unheimlich indeed.

The early Surrealists, led by André Breton, were deeply influenced by Freud. Freud saw the house as a symbol for the body, and thus, as with bodies, by definition an object that is subject to decay, to ultimate disintegration. Perhaps even more influential was the German word for the uncanny – unheimlich, un-home-like. Houses seem to define our sense of place, and so it is a brilliantly conceived stroke to begin the exhibition with two iconic pieces of house-less-ness: Buster Keaton in Steamboat Bill Jr, desperately trying to escape a hurricane, and time after time having his house physically disappear; and Marcel Duchamp’s Fresh Widow (1920, pictured right), his alter-ego Rhose Sélavy’s first work (right), in which the glass, the function and purpose of windows, is replaced by shiny black leather – the elements of sexuality, of skin and therefore of danger, make the usually transparent window unheimlich indeed.

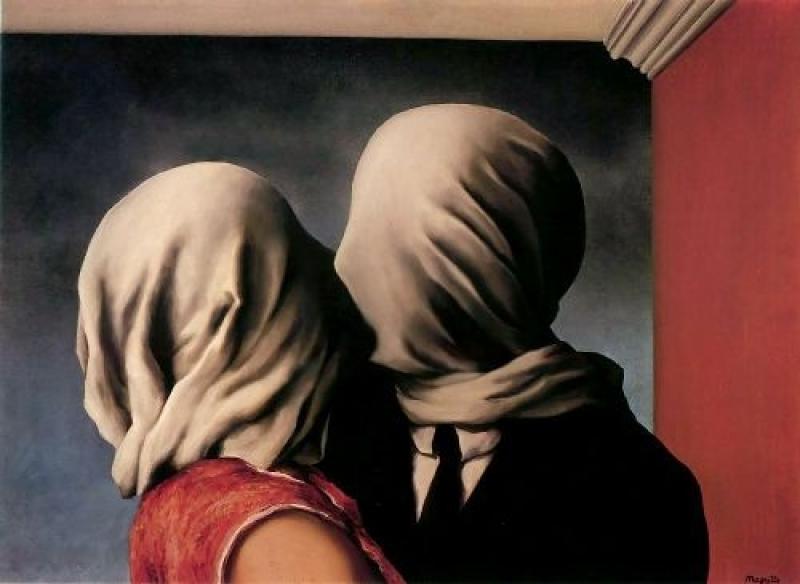

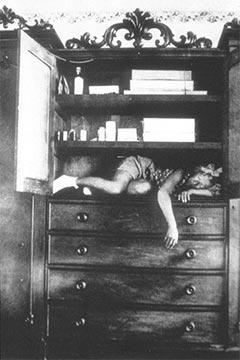

And this is the core of what Surrealism is about: it is a means of harnessing the uncanniness of the unconscious mind, combining it with the bizarre rational illogicality of dreams and – at least in its original form – reproducing this mélange in hyper-realistic style. René Magritte and Dalí, each in their different ways, are today the paradigmatic Surrealist creators, but the great treat of this show is the number of half-known or unknown names it presents. Claude Cahun, the 1930s photographer, writer and proto-performance-artist, is represented by one of her staged images, Self-portrait (in cupboard) (pictured below), where the detail of the items in the cupboard fetishise the body of the photographer: just one more thing to find shelf-space for.

The tragically short career of the photographer Francesca Woodman, who killed herself aged 22, is given the space it deserves, with part of her House images, with distressed walls and half-vanished bodies. At the other end of the age-scale, Louise Bourgeois’ long career is well represented, with, in particular, No Exit, where two balls guard a staircase to nowhere, itself having its secrets shrouded by screens; what is behind, beneath, below, is the ultimate mystery. Her small, and fairly atypical, Femme maison is equally beguiling - woman into house indeed. There are, however, a number of pieces that simply don’t belong. They are quirky, or camp, or kitsch, or just plain funny, but they are not surreal: oddity alone is not surreal, illogic is not surreal. Without this element, it is like these pieces have somehow wandered into the wrong party. Rebecca Horn’s grandiose Concert for Anarchy, in which a piano is hung in the air upside down, with its striking elements hanging out and unharmoniously sounding, takes an object and denudes it of its purpose, but that is not Surrealism. Nor is Sara Lucas’s well-known Au naturel, perkily comic though it remains, and its ancestor, Magritte’s Homage à Mack Sennett, a picture of a woman’s body hanging neatly in a cupboard, tucked away until it is needed once more, is only a few rooms away.

There are, however, a number of pieces that simply don’t belong. They are quirky, or camp, or kitsch, or just plain funny, but they are not surreal: oddity alone is not surreal, illogic is not surreal. Without this element, it is like these pieces have somehow wandered into the wrong party. Rebecca Horn’s grandiose Concert for Anarchy, in which a piano is hung in the air upside down, with its striking elements hanging out and unharmoniously sounding, takes an object and denudes it of its purpose, but that is not Surrealism. Nor is Sara Lucas’s well-known Au naturel, perkily comic though it remains, and its ancestor, Magritte’s Homage à Mack Sennett, a picture of a woman’s body hanging neatly in a cupboard, tucked away until it is needed once more, is only a few rooms away.

But with a collection of extraordinarily fine works – in particular, five gorgeous, creepy, touching and mysteriously unreachable Joseph Cornell pieces – the oddities pale by comparison. The Cornells alone are worth a visit. So is the bizarre and terrifying Ed Kienholz, The Wait, where a mother-figure is constructed of clothes and a series of jars filled with symbols of her meaning: crosses, household objects, a locket; she sits in a dust-covered 1950s room, next to photographs of all the absent presence in her non-life. So is a whole series of rooms on surreal architecture, including Gordon Matta-Clark’s famous photograph, Splitting, and a series of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret images.

The richness of the symbolism is matched by the richness of the myriad levels of ideas that are there for exploration, and also by the sheer quantity of material on display: an entire summer can happily be spent exploring The Surreal House.

- The Surreal House at the Barbican Art Gallery until 12 September

- Films, talks and events relating to The Surreal House

Watch Louise Bourgeois on YouTube

Picture credits. Marcel Duchamp: Fresh Widow, 1920 (replica 1964) (© Tate, London, 2010 © Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2010); Claude Cahun, Self-portrait (in cupboard), c.1932 (courtesy of Jersey Heritage Collections)

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name