Reissue CDs Weekly: The Beatles - Abbey Road | reviews, news & interviews

Reissue CDs Weekly: The Beatles - Abbey Road

Reissue CDs Weekly: The Beatles - Abbey Road

Fifty years on, the last album The Fabs recorded is remodelled

Among the issues integral to the final album The Beatles recorded two, though usually low profile, are worth bearing mind. Abbey Road was their first album to be released in stereo only. There was no mono edition.

The album was recorded in a new world, one where the old – mono and valves – was being ushered out. And likewise, The Beatles were in the studio as they ushered themselves out. They knew the dream was over.

That was 50 years ago, and as it was with the same anniversary for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and The Beatles (the White Album) a new edition of Abbey Road is being released. It comes in multiple formats. There’s a “Super Deluxe” three-CD and Blu-ray set, a three-LP vinyl box set promoted as a limited edition (the number of copies manufactured is not revealed), a two-CD version and “Standard” editions of either a single CD, a download, a single-LP on vinyl and a single-LP picture-disc version (also limited, and again the number of copies manufactured is not revealed).

That was 50 years ago, and as it was with the same anniversary for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and The Beatles (the White Album) a new edition of Abbey Road is being released. It comes in multiple formats. There’s a “Super Deluxe” three-CD and Blu-ray set, a three-LP vinyl box set promoted as a limited edition (the number of copies manufactured is not revealed), a two-CD version and “Standard” editions of either a single CD, a download, a single-LP on vinyl and a single-LP picture-disc version (also limited, and again the number of copies manufactured is not revealed).

As per the Pepper and White Album anniversary packages, a major aspect of the new release is a freshly created remix of album by George Martin’s son Giles. In the “Super Deluxe” version, there are also two discs titled “Sessions” collecting demos, backing tracks, work in progress from the album sessions, the original version of the album’s Side Two medley and George Martin’s scores for “Something” and “Golden Slumbers”/“Carry That Weight”. A fourth disc, a Blu-Ray, includes a Dolby Atmos version of the new album remix, plus 96kHz/24 bit DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 and 96kHz/24 bit high-res stereo versions of the same. These latter three items were not offered for review. There is also a 100-page hardback book in the “Super Deluxe” version. A pdf of it was requested but, disappointingly, no copy was sent.

Not all of Abbey Road was recorded and mixed in the newly transistorised Studio 2 but in its original form it remains the most modern-sounding Beatles’ album. That is, today’s ears hear it as analogous with what came later rather than what came before. Of course, an aspect of this is to do with its songs. “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” is very 1969, a performance and song in keeping with notions of rock as it bedded in during the Seventies.

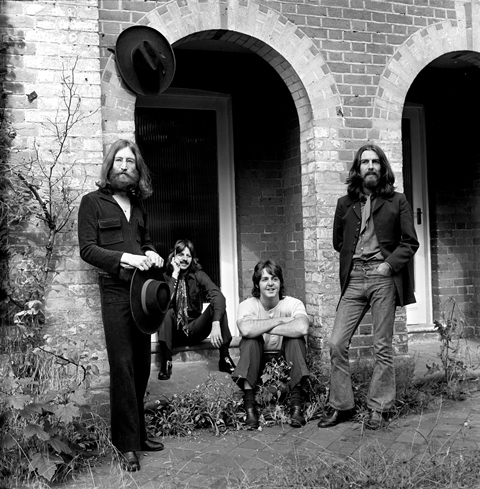

Abbey Road is further disconnected from other Beatles’ albums as it was completed after recording the intended Get Back album which was issued as Let It Be in 1970. Even in 1969, Abbey Road was disengaged from the band’s chain of events. In this scrambled chronology, it featured songs which were White Album leftovers and/or a year old (“Something”, “Octopus’s Garden”, “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer”, “Mean Mr Mustard”, “Polythene Pam”), Get Back session tracks which were reworked or completed (“Oh Darling!”, “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer”, “She Came in Through the Bathroom Window”, “I Want You (She’s so Heavy)”) and fragments of incomplete songs only rendered releasable after being dovetailed into the album’s Side Two medley. (Pictured above, The Beatles, 22 August 1969)

Abbey Road is further disconnected from other Beatles’ albums as it was completed after recording the intended Get Back album which was issued as Let It Be in 1970. Even in 1969, Abbey Road was disengaged from the band’s chain of events. In this scrambled chronology, it featured songs which were White Album leftovers and/or a year old (“Something”, “Octopus’s Garden”, “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer”, “Mean Mr Mustard”, “Polythene Pam”), Get Back session tracks which were reworked or completed (“Oh Darling!”, “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer”, “She Came in Through the Bathroom Window”, “I Want You (She’s so Heavy)”) and fragments of incomplete songs only rendered releasable after being dovetailed into the album’s Side Two medley. (Pictured above, The Beatles, 22 August 1969)

Set all this alongside George Harrison temporarily leaving the band during the Get Back sessions, three of them signing Allen Klein as their manager and Paul McCartney pitching in with his new wife’s father as his manager, the presence of a bedded Yoko Ono in the studio, John Lennon initially pushing for his songs on one side of the album and McCartney’s on the other, and many more disruptive factors (including Ono taking one of Harrison’s biscuits), it’s a wonder anything cohesive was completed. The standard reason for this is that The Beatles knew they had reached the finishing line and were giving it one last shot; the narrative which 50th-anniversary version buys into. Whatever the fissures, money issues, petulance and sundered relationships, music united the bickering foursome.

Ostensibly, the “Super Deluxe” edition's two discs of demos, sessions, etc. would provide a window on what actually went on. But things may not be what they seem. Audio verité is not necessarily the order of the day. George Harrison’s 25 February demo of “Something” was first heard on Anthology 3 in 1996. Here, it is subjected to a “new anniversary mix”. The version of “The Ballad of John and Yoko” is given as Take 7 in the tracklist yet the John and Paul chat heard before the song gets going is actually from just before takes two and four (“Un string avec caput Mal”, “It’s got a bit faster, Ringo”, “OK George”).

Ostensibly, the “Super Deluxe” edition's two discs of demos, sessions, etc. would provide a window on what actually went on. But things may not be what they seem. Audio verité is not necessarily the order of the day. George Harrison’s 25 February demo of “Something” was first heard on Anthology 3 in 1996. Here, it is subjected to a “new anniversary mix”. The version of “The Ballad of John and Yoko” is given as Take 7 in the tracklist yet the John and Paul chat heard before the song gets going is actually from just before takes two and four (“Un string avec caput Mal”, “It’s got a bit faster, Ringo”, “OK George”).

Notwithstanding any reservations about after-the-fact modifications, it’s fascinating that the first of the “Sessions” CDs begins with a 22 February 1969 run-through of “I Want You (She’s so Heavy)” from Trident Studios which was intended for the then still-live Get Back album. The bleed between this and Abbey Road is instantly acknowledged. The “Get Back” single was issued on 11 April, after the taping of the demos of “Goodbye” and ”Something” heard here. In-progress versions of “The Ballad of John and Yoko” and ”Old Brown Shoe” are from 14 and 16 April. Take 4 of “Oh! Darling” was tracked on 20 April. The first version of the Get Back album master was created on 28 May. As-such recording for what was later titled Abbey Road was undertaken from 1 July to 29 August, and initially without Lennon – who began working on the album from 9 July as he and Ono had been in a car accident. On 1 July, McCartney alone worked on “You Never Give Me Your Money”. More than chronicling the album, the new Abbey Road is further confirmation of the rudderlessness within Beatle world.

Of the in-progress session tracks, the most immediately interesting is Take 36 of “You Never Give Me Your Money” which, as McCartney says, was recorded at 2.30am. What was released, though, was built from the foundation of Take 30, so it’s now possible to hear what was shelved in favour of what was deemed best. Here, McCartney’s voice is softer and there is more of a chugging, rock feel as the song progresses especially in Harrison’s stabbing guitar.

Another insight into where a song could have ended up comes with a Take 9 (of 13) of “Here Comes the Sun” where Ringo’s drumming doesn’t quite gel with the rhythm of the guitar. More work was needed. With Take 12 of “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer”, McCartney decides more work is needed – he is heard directing Ringo’s drumming. (Pictured abve, The Beatles, 22 August 1969)

Another insight into where a song could have ended up comes with a Take 9 (of 13) of “Here Comes the Sun” where Ringo’s drumming doesn’t quite gel with the rhythm of the guitar. More work was needed. With Take 12 of “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer”, McCartney decides more work is needed – he is heard directing Ringo’s drumming. (Pictured abve, The Beatles, 22 August 1969)

In contrast 21 July’s Take 5 of “Come Together” (eight were recorded, of which take six was best), while skeletal and breaking down at 02.55, shows that the song was fully formed before further work was undertaken. Most enjoyable is Take 3 of “The End”, which shows that jamming could coalesce into a performance with real drive. It’s funny to hear a non-medley “Mean Mr Mustard” peter out at 01.13. There really was no more to this song. It is also amusing to hear Lennon saying that the drums on a “Polythene Pam” try-out – Take 27 of this trifle was recorded contiguously with “She Came in Through the Bathroom Window” – “sound like Dave Clark”. A separate take, Take 39 (not heard here), was devoted to recording a new drum track, the one which was used. It’s bizarre to hear “Her Majesty” embedded in the Side Two medley, between “Mean Mr Mustard” and “Polythene Pam”.

The “Sessions” discs are not revelatory but nonetheless add to the understanding of how The Beatles did things, so are important. But not as much so as discovering previously hidden narratives of Sgt. Pepper’s and the White Album. Nothing changes the view that The Beatles of 1969 were falling apart while seeking to paper over the cracks.

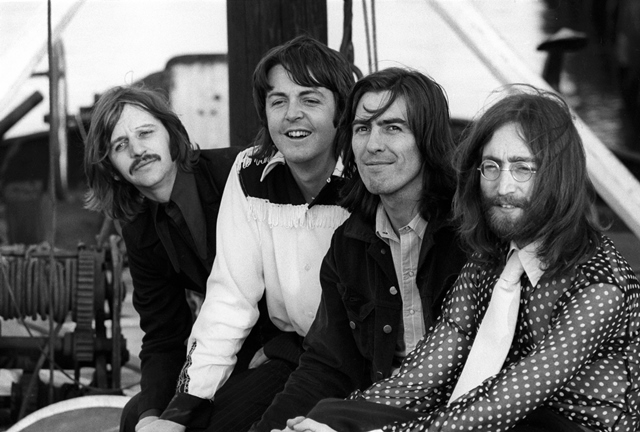

However, Disc One’s remix actively seeks to change views of Abbey Road. Giles Martin’s work is in line with what he did to the White Album. There is a new separation and an added clarity which certainly brings a new punch. “The magic comes from the hands playing the instruments, the blend of The Beatles’ voices, the beauty of the arrangements,” says Giles Martin in the press material. “Our quest is simply to ensure everything sounds as fresh and hits you as hard as it would have on the day it was recorded.” The result is like a Butch Vig production, or similar to the hard edge of The Posies on their Frosting on the Beater album: i.e. when a modern-day production tries to sound classic, late Sixties. Also, however this was created, the resultant punch feels coldly digital. The fuzzy warmth which helped define the album is missing. (Pictured above, The Beatles, 9 April 1969)

However, Disc One’s remix actively seeks to change views of Abbey Road. Giles Martin’s work is in line with what he did to the White Album. There is a new separation and an added clarity which certainly brings a new punch. “The magic comes from the hands playing the instruments, the blend of The Beatles’ voices, the beauty of the arrangements,” says Giles Martin in the press material. “Our quest is simply to ensure everything sounds as fresh and hits you as hard as it would have on the day it was recorded.” The result is like a Butch Vig production, or similar to the hard edge of The Posies on their Frosting on the Beater album: i.e. when a modern-day production tries to sound classic, late Sixties. Also, however this was created, the resultant punch feels coldly digital. The fuzzy warmth which helped define the album is missing. (Pictured above, The Beatles, 9 April 1969)

The major new characteristic is a fondness for the drums, now so up-front they distract from the whole. From when “Come Together” starts, the ear is drawn drum-wards. The separation overall leads to some jarring moments: the pizzicato strings on “Something” distract, as do “Here Comes the Sun’s” handclaps. At 01.58 in “I Want You (She’s so Heavy)”, Billy Preston’s organ is so to the fore it derails proceedings. Why is the organ at 01.34 on “Sun King” so loud? Oddly and contrastingly, “Mean Mr Mustard” has been flattened out. Ultimately, it is impossible to understand the point of the remix. Abbey Road was the album it was, and that has been perfectly fine for five decades. Changing it into something else is unnecessary.

Some loose ends remain. What’s missing from the audio are the mono mix made on 18 July of “Octopus’s Garden”, mono versions of “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” and Get Back’s “Dig it” made on 11 August, and the 2 and 8 December versions of “Octopus’s Garden” made for the George Martin TV show With a little Help From my Friends. It’d also be great to hear the full tracking session of McCartney’s “Come and Get it” rather than the extract included here.

Of the 50th-anniversary trio of Beatles’ albums issued so far, the new Abbey Road is the least essential and raises questions about what’s next. It’s known that the raw footage for what became the Let it be film is being revisited, presumably for something to be released next year. The following year will mark 55 years since the release of Revolver. As John Lennon would later sing, “I'm just sittin' here watchin' the wheels go round and round.”

- Next week: The De La Soul-inspired compilation The Daisy Age

- Read more reissue reviews on theartsdesk

- Kieron Tyler’s website

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Album: Saint Etienne - International

British pop institution’s final communiqué is an unalloyed winner

Album: Saint Etienne - International

British pop institution’s final communiqué is an unalloyed winner

Album: Brad Mehldau - Ride into the Sun

A sincere tribute to Elliott Smith

Album: Brad Mehldau - Ride into the Sun

A sincere tribute to Elliott Smith

Music Reissues Weekly: The Outer Limits - Just One More Chance

Exhaustive anthology unearths the full story of the Sixties mod-pop band from Leeds

Music Reissues Weekly: The Outer Limits - Just One More Chance

Exhaustive anthology unearths the full story of the Sixties mod-pop band from Leeds

theartsdesk Radio Show 37 - Pete Lawrence of the Big Chill discusses the power of protest music and his new project This Is The Fire

Talking to cultural activist Pete Lawrence – camp outs, singalongs and saving the world

theartsdesk Radio Show 37 - Pete Lawrence of the Big Chill discusses the power of protest music and his new project This Is The Fire

Talking to cultural activist Pete Lawrence – camp outs, singalongs and saving the world

Album: Sabrina Carpenter - Man's Best Friend

Short but not so sweet

Album: Sabrina Carpenter - Man's Best Friend

Short but not so sweet

Album: CMAT - EURO-COUNTRY

The flame-headed chanteuse with the comic touch hits pop perfection

Album: CMAT - EURO-COUNTRY

The flame-headed chanteuse with the comic touch hits pop perfection

Album: The Hives - The Hives Forever, Forever The Hives

No power ballads, no acoustic interludes - just speedy rock’n’roll all the way

Album: The Hives - The Hives Forever, Forever The Hives

No power ballads, no acoustic interludes - just speedy rock’n’roll all the way

Album: Benedicte Maurseth - Mirra

Haunting, intense evocation of Norway’s uplands and its wildlife

Album: Benedicte Maurseth - Mirra

Haunting, intense evocation of Norway’s uplands and its wildlife

Album: Nova Twins - Parasites & Butterflies

Exciting London duo turn inward and more introspective with their third album while retaining their trademark hybrid sound

Album: Nova Twins - Parasites & Butterflies

Exciting London duo turn inward and more introspective with their third album while retaining their trademark hybrid sound

Music Reissues Weekly: The Beatles - What's The New, Mary Jane

John Lennon’s queasy, see-sawing oddity becomes the subject of a whole album

Music Reissues Weekly: The Beatles - What's The New, Mary Jane

John Lennon’s queasy, see-sawing oddity becomes the subject of a whole album

The Maccabees, Barrowland, Glasgow review - indie band return with both emotion and quality

The five-piece's reunion showed their music has stood the test of time.

The Maccabees, Barrowland, Glasgow review - indie band return with both emotion and quality

The five-piece's reunion showed their music has stood the test of time.

Album: Blood Orange - Essex Honey

A triumph for the artist who doesn't clamour for attention but just keeps growing

Album: Blood Orange - Essex Honey

A triumph for the artist who doesn't clamour for attention but just keeps growing

Comments

George Martin: "tape is an

Wow. Don't agree at all. Don

Music has evolved