theartsdesk in Denmark: 150 years of Nielsen | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Denmark: 150 years of Nielsen

theartsdesk in Denmark: 150 years of Nielsen

A great symphonist and a national treasure celebrated at home

Music-lovers outside Denmark will have come to know Carl Nielsen (1865-1931) through his shatteringly vital symphonies as one of the world-class greats, a figure of light, darkness and every human shade in between. For Danes it is different: since childhood, most have been singing at least a dozen of his simpler songs in community gatherings, probably without even knowing the name of the composer.

The forthright, folk-square sentiments and the melodies that seem to have part of the Danish fabric for centuries are a part of the national heritage but haven’t travelled abroad. So the general consensus about Nielsen in Copenhagen and Odense, Denmark’s third city close to his very humble birthplace, tends to have been of a straightforward national monument. The 150th anniversary celebrations have been changing all that, and on his birthday on 9 June you could take your pick between a grand opera, an orchestral gala and folk-oriented celebrations complete with children’s ensembles inside (in Odense’s concert hall) or out (on the lawns of Nielsen’s childhood home).

The evening of the big day was what I most anticipated: the chance to see on stage at last the serious king of his two operas, Saul and David (pictured right in the first of two production images by Signe Rodesrik, Morten Staugaard as Samuel and Johan Reuter as Saul). It’s been a more conspicuous absentee from the world’s repertoire than Polish composer Szymanowski’s Krol Roger, which the Danish leader of London’s Royal Opera Kasper Holten finally brought to Covent Garden. Nielsen’s musical language is much more personal: seemingly direct, full of unusual polyphony and built on firm ground which, as in the absolutely contemporary Second Symphony of 1902, slips or opens up to reveal chasms. To follow its journey into the even stranger terrains of his greatest masterpieces, the Fifth Symphony of 1922 and the Sixth, the very misleadingly named "Sinfonia Semplice", is to find a life of stress versus charming ease, sheer heart-attack (literally), glimpses into a world beyond and an enormous, sometimes manic vitality shot through with earthy humour.

The evening of the big day was what I most anticipated: the chance to see on stage at last the serious king of his two operas, Saul and David (pictured right in the first of two production images by Signe Rodesrik, Morten Staugaard as Samuel and Johan Reuter as Saul). It’s been a more conspicuous absentee from the world’s repertoire than Polish composer Szymanowski’s Krol Roger, which the Danish leader of London’s Royal Opera Kasper Holten finally brought to Covent Garden. Nielsen’s musical language is much more personal: seemingly direct, full of unusual polyphony and built on firm ground which, as in the absolutely contemporary Second Symphony of 1902, slips or opens up to reveal chasms. To follow its journey into the even stranger terrains of his greatest masterpieces, the Fifth Symphony of 1922 and the Sixth, the very misleadingly named "Sinfonia Semplice", is to find a life of stress versus charming ease, sheer heart-attack (literally), glimpses into a world beyond and an enormous, sometimes manic vitality shot through with earthy humour.

The picture of a very human but sometimes elusive man has been built up by generously government-funded research, done with Danish thoroughness and handsomely presented in several spheres we found out more about on a morning visit to Copenhagen’s Royal Library, its handsome core extended in 1999 by the so-called Black Diamond (pictured below), an architectural wonder which puts our own British Library as well as the somewhat overpraised recent venue of the Danish Royal Opera rather in the shade.

In this most genially civilized of cities, where summer life is lived on the streets in a way Britain hasn’t quite managed to adopt, the big-thinking of new architecture sits easily along the harbour with the townish intimacy of the city centre. A permanent exhibition, Treasures of the Royal Library, is a typically quirky mix: framed by playful graphics from Russian artist Andrey Bartenev, the manuscript clean copy of Nielsen’s Fourth Symphony shares honours with the Gutenberg Bible, Bach’s Cantata “Mein Herz schwimmt in blut”, draft pages of Tolstoy’s War and Peace and, of course, self-illustrated Hans Christian Andersen.

In this most genially civilized of cities, where summer life is lived on the streets in a way Britain hasn’t quite managed to adopt, the big-thinking of new architecture sits easily along the harbour with the townish intimacy of the city centre. A permanent exhibition, Treasures of the Royal Library, is a typically quirky mix: framed by playful graphics from Russian artist Andrey Bartenev, the manuscript clean copy of Nielsen’s Fourth Symphony shares honours with the Gutenberg Bible, Bach’s Cantata “Mein Herz schwimmt in blut”, draft pages of Tolstoy’s War and Peace and, of course, self-illustrated Hans Christian Andersen.

Nielsen research here has mushroomed relatively recently. In 1996 a third of the composer’s prolific output had never been published. By 2009 there were 52 volumes. Editor-in-chief Niels Krabbe, a brilliant speaker who should have been invited over in the UK to introduce the instalments of Sakari Oramo’s BBC Symphony Orchestra Nielsen cycle, joked that the (rather crucially placed) change of a note in Nielsen’s nationally adored comic opera Maskarade cost 42 million kronor – though of course that’s the sum of the total work, undertaken by five people over 15 years.

In addition there’s what they call the “final digital thematic-bibliographic Catalogue of Carl Nielsen’s works”, an amazing resource which allows you to download each and every score complete. Apparently it’s easier to see the music in a parallel version on the very handsome website, produced by Dominik Falenski, whom we met later at the gargantuan new headquarters of Danish Radio. Charming director of programming Tatjana Kandel guided us over a glass bridge from the office spaces to the stupendous concert hall designed by Jean Nouvel (pictured below at the start of rehearsal). It’s official, this is one of the best acoustics in the world, if not the best, because Daniel Barenboim recently said so.

The approach is odd – the foyer space is actually under the hall, with packing cases for seats and a ceiling which is supposed to represent the underside of a meteor that’s crashed through the building.

The approach is odd – the foyer space is actually under the hall, with packing cases for seats and a ceiling which is supposed to represent the underside of a meteor that’s crashed through the building.

You gasp, as you’re supposed to, on entering the hall with its wavy panels of wood and a Berlin Philharmonie-inspired democratic audience ring around the orchestra. As in Berlin, there can’t be a bad seat in the house. And it has a gem of an orchestra, the Danish National (Radio) Symphony Orchestra which brought one of the most original programmes ever to the Proms in 2010 and will be returning with another – mostly Nielsen, conducted by Fabio Luisi – on 20 August. The DNSO is an orchestra with a very natural – which means a very Danish – voice; on my return I’d learn from Vladimir Ashkenazy, who is conducting this team in two Sixth Symphonies – Nielsen’s and Shostakovich’s – next season that it’s one he especially loves.

We were lucky to catch a rehearsal for two of the three pieces in that evening’s concert we’d have to sacrifice to Saul and David (Hymnus Amoris, the missing element along with a surprise choral tribute, we can catch from the DNSO at the Proms). Finnish principal clarinettist Olli Leppäniemi was the liquid chameleon of the late Clarinet Concerto, in fluid accord with his colleagues as one would expect; Juanjo Mena, well known to us through his energetic work with the BBC Philharmonic, took the orchestra through one of several Danish performances of the Fourth (“Inextinguishable”) Symphony.

Another had just taken place in Odense with its resident symphony orchestra conducted by Thomas Dausgaard, and I’d rather have heard both in full concert than the one we were so curious, if wary, to experience from the Vienna Philharmonic and all too extinguishable-in-the-memory Franz Welser-Möst the next night. It’s unfair to judge a rehearsal – presumably Mena would fire up the interpretation later – but the sense of focus and movement was unerring, vintage Nielsen, with some extraordinary work from the two bassoonists. It would be a gripe of the Odense event that the Vienna Philharmonic woodwind are so mellifluous but by comparison so lacking in individuality.

The afternoon was spent in the old Danish National Theatre, which still hosts Mozart, Handel and Gluck but can’t properly accommodate Wagner and Strauss. That was one reason for the building of the lavish new opera house (Operan) over the water. Nielsen as Tamino greeted us in the mosaic of great Danes on the roof of the passageway connecting the theatre with Danish Radio's first headquarters (pictured above).

The afternoon was spent in the old Danish National Theatre, which still hosts Mozart, Handel and Gluck but can’t properly accommodate Wagner and Strauss. That was one reason for the building of the lavish new opera house (Operan) over the water. Nielsen as Tamino greeted us in the mosaic of great Danes on the roof of the passageway connecting the theatre with Danish Radio's first headquarters (pictured above).

Saul and David, Maskarade and Oehlenschlager’s four-hour oriental extravaganza Aladdin in the version with substantial incidental music by Nielsen – would we could hear it in some sort of context – were all premiered here. And the 12 volumes of every letter Nielsen wrote, along with many he received, have been revelatory not just to the life but also to the execution of his works in such details as how the Third "Espansiva" Symphony was performed here: the wordless baritone solo in the slow movement was declaimed from the wings, the answering soprano from on high in the central dome. Invariably they’re side by side in the body of the orchestra, which makes for a completely different effect.

In the "green room", with portraits of distinguished actors and musicians on the wall, something Scandinavian theatres do so much better than us, the editor of the letters, Dane John Fellow, seemed disgruntled when I expressed my joy that a two-volume selection, translated by my excellent colleague David Fanning with checking by Krabbe, would be published soon: “Nothing to do with me”. You’d think all Nielsen musicologists would be delighted at the dissemination. One who clearly is, the Royal Danish Orchestra's chief conductor until 2011 Michael Schønwandt (pictured to the right of Fellow), turned out to be a figure of irrepressible delight, speaking the most musical and perfect English (he trained at London's Royal Academy of Music). He’s conducted so much superb Nielsen, and is in charge of the rollicking Maskarade just released on the pioneering Danish label Dacapo. He pointed out that though he wasn’t nationalistic, he had such immense pride that Nielsen could be both the composer of the simple songs every Dane knows and the most extraordinary visionary in the symphonies. He also said his view of Nielsen, and especially of the darker side, gleaned from the letters had changed his interpretations: “For example, I now conduct the [very complex] third movement of the 'Espansiva' completely differently.”

In the "green room", with portraits of distinguished actors and musicians on the wall, something Scandinavian theatres do so much better than us, the editor of the letters, Dane John Fellow, seemed disgruntled when I expressed my joy that a two-volume selection, translated by my excellent colleague David Fanning with checking by Krabbe, would be published soon: “Nothing to do with me”. You’d think all Nielsen musicologists would be delighted at the dissemination. One who clearly is, the Royal Danish Orchestra's chief conductor until 2011 Michael Schønwandt (pictured to the right of Fellow), turned out to be a figure of irrepressible delight, speaking the most musical and perfect English (he trained at London's Royal Academy of Music). He’s conducted so much superb Nielsen, and is in charge of the rollicking Maskarade just released on the pioneering Danish label Dacapo. He pointed out that though he wasn’t nationalistic, he had such immense pride that Nielsen could be both the composer of the simple songs every Dane knows and the most extraordinary visionary in the symphonies. He also said his view of Nielsen, and especially of the darker side, gleaned from the letters had changed his interpretations: “For example, I now conduct the [very complex] third movement of the 'Espansiva' completely differently.”

At any rate, as we could see from two rows back in the stalls of the imposing new Opera House that evening, Schønwandt conducted Saul and David with ideally natural flexibility, aided by some of the most exquisite wind playing I’ve heard from an orchestra (superb first oboist of the Royal Danish Orchestra Henrik Goldschmidt contributed a fascinating article on the Middle Eastern background of the opera). David Pountney’s production, with the populace watching the public drama of Saul’s condemnation by fundamentalist Samuel and his soothing by David’s lyre on television scenes in a crumbling concrete apartment block, did nothing to change the commonly-held view that this is more oratorio than opera. Despite Nielsen’s absolutely distinctive language, there are parallels with Handel, especially in the fugal chorus of the third act.

At any rate, as we could see from two rows back in the stalls of the imposing new Opera House that evening, Schønwandt conducted Saul and David with ideally natural flexibility, aided by some of the most exquisite wind playing I’ve heard from an orchestra (superb first oboist of the Royal Danish Orchestra Henrik Goldschmidt contributed a fascinating article on the Middle Eastern background of the opera). David Pountney’s production, with the populace watching the public drama of Saul’s condemnation by fundamentalist Samuel and his soothing by David’s lyre on television scenes in a crumbling concrete apartment block, did nothing to change the commonly-held view that this is more oratorio than opera. Despite Nielsen’s absolutely distinctive language, there are parallels with Handel, especially in the fugal chorus of the third act.

The more complex side of the piece is crystallized when heroic baritone Johan Reuter’s Saul (pictured above) sinks into a depression, only to be soothed by the song of David (Heldentenor Niels Jorgen Riis, more shaggy Jokanaan in Salome than beautiful boy). Nielsen himself embraced both sides, and more; Schønwandt bought my suggestion that the “Four Temperaments” of the absolutely contemporary Second Symphony are aspects of the composer, and suitably interwoven in each movement.

So we had our vision, and a wreath-laying on a bust of Nielsen in the spectacular foyer (pictured right) following a flute and harp tribute during the interval. Early the next morning, it was off to Odense, the real Nielsen heartland on the island of Funen. All you need to know about his hard but never unhappy childhood is contained in My Childhood, a masterpiece of autobiography which should be read by everyone. Sadly it’s not been reprinted in English this anniversary year.

So we had our vision, and a wreath-laying on a bust of Nielsen in the spectacular foyer (pictured right) following a flute and harp tribute during the interval. Early the next morning, it was off to Odense, the real Nielsen heartland on the island of Funen. All you need to know about his hard but never unhappy childhood is contained in My Childhood, a masterpiece of autobiography which should be read by everyone. Sadly it’s not been reprinted in English this anniversary year.

The house-museum near Nørre-Lyndelse outside Odense isn’t the birthplace, a small cottage in the middle of a field housing two large families when Nielsen was born; that’s marked now by a stone. The second home played host to what looks like a wonderful range of youth-oriented activities the day before we arrived (pictured above). Nielsen describes the move with typical poetic homage to his mother:

One day Mother and I were going to Allestad. We walked in a heat haze along the road from Nørre-Lyndelse to Nørre-Soby. A couple of hundred paces past the Lumby-Lumbyholm crossroads Mother stopped rather suddenly and gazed over the landscape to the south-east, where there is an extensive view. “Look, now it’s there again! Everything is so beautiful, and I see the loveliest towers and spires; and just listen to the bells ringing. Why is it that I should see so many things that other people laugh at and Daddy says I only imagine?” I saw nothing but the green and yellow fields, enclosed by willow hedges and broken by scattered farms and cottages right over towards Palleshave and Nordskov. But Mother looked glad and happy, and we walked on. Shortly after, she again stopped suddenly, by a roadside cottage near the parish boundary between Nørre-Lyndelse and Nørre-Soby. It was a handsome, brick-built thatched cottage with seven windows and a long, narrow garden intersected by the road. In one half of the garden were two pear-trees, in the other a couple of cherries and an elder-bush. It was a summer day and the potatoes were in flower. My mother confided in me that she would like to own this house. I must have said something about its being quite beyond our means, for I remember the words she said: “When we wish for something with all our hearts, we must keep on thinking of it, and we shall get it in the end.” The whole property cost 1,150 kronor, with a deposit of an 300-400 kronor.

A year later we actually moved into this palace of sun and light and gladness.

The little house (pictured right) makes a beautiful counterpart to the humble dwellings into which Hans Christian Andersen was born under similar circumstances, a tiny dwelling in what now seem like impossibly quaint Odense streets but which at the time were slums in the red-light district. It now has a huge and well designed exhibition space attached, due to move to premises under a park soon. We had all too short a time there with the enthusiastic curator, Einar Askgaard, revelatory about Nielsen’s many artistic skills – not just the famous paper cut-outs, but also collages and singular sketches. The overall director of Odense’s museums, Torben Grønnegard Jeppesen, told us that when JK Rowling came here as recipient of the Andersen Prize, she sat in one of the tiny rooms and wept, remembering her own impoverished childhood.

The little house (pictured right) makes a beautiful counterpart to the humble dwellings into which Hans Christian Andersen was born under similar circumstances, a tiny dwelling in what now seem like impossibly quaint Odense streets but which at the time were slums in the red-light district. It now has a huge and well designed exhibition space attached, due to move to premises under a park soon. We had all too short a time there with the enthusiastic curator, Einar Askgaard, revelatory about Nielsen’s many artistic skills – not just the famous paper cut-outs, but also collages and singular sketches. The overall director of Odense’s museums, Torben Grønnegard Jeppesen, told us that when JK Rowling came here as recipient of the Andersen Prize, she sat in one of the tiny rooms and wept, remembering her own impoverished childhood.

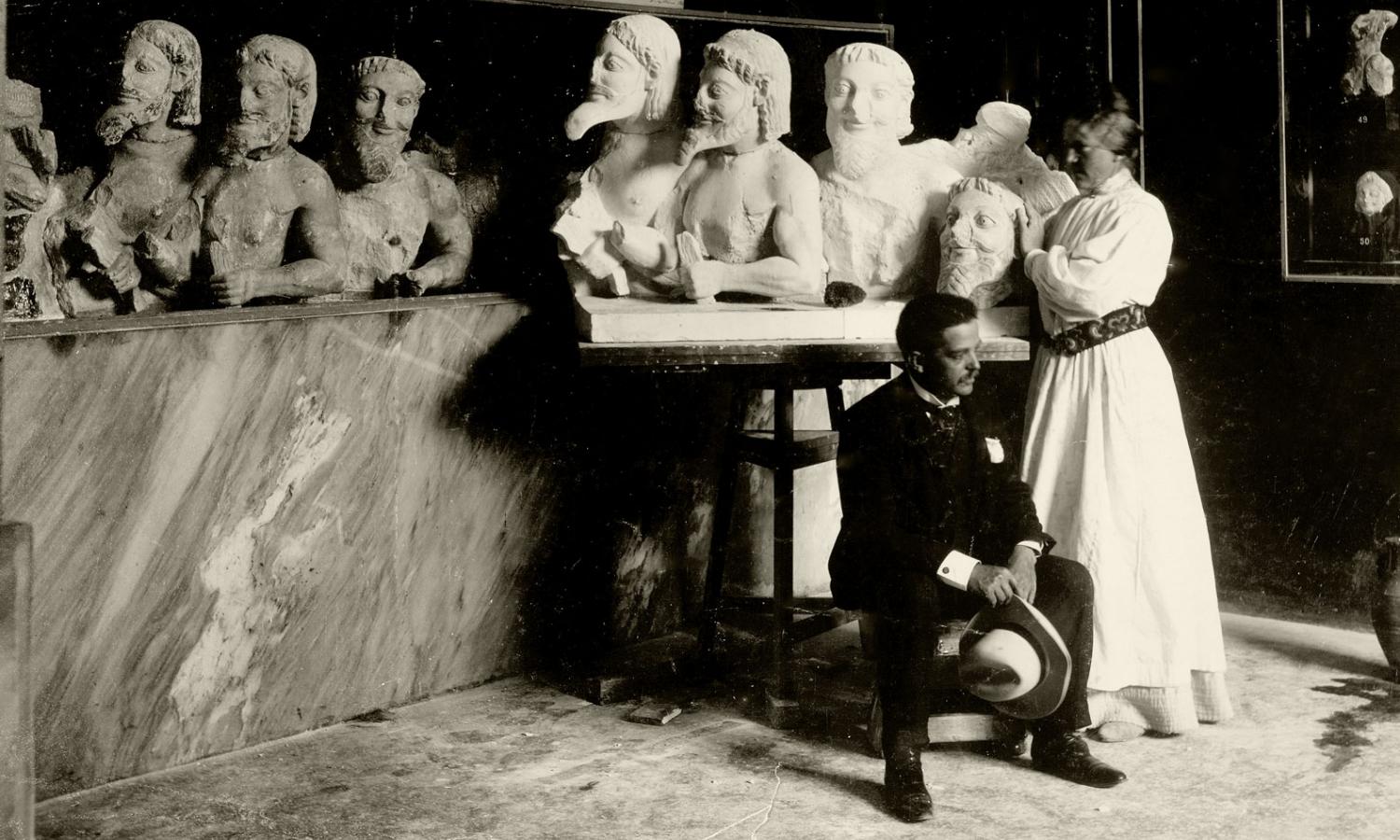

Nielsen’s childhood home is beautifully kept, with jugs and vases of wild flowers on the windowsills just as Nielsen recalls his mother arranging, and plentiful objects to complement the rich display in Odense’s Carl Nielsen Museum adjoining the concert hall (a new theatre and opera house is under construction alongside, due to open in 2017 with a cycle of Wagner’s Ring operas). As its curator, singer and Nielsen lover Ida-Marie Vorre, pointed out, it should really be called the Carl and Anne Marie Nielsen Museum, for this beautiful display is equally a homage to Anne Marie’s talent as a sculptor, with plenty of her models and smaller sculptures (pictured above, Anne Marie working on a copy of the Parthenon hydra in Athens during 1903 while Nielsen sits). What a remarkable woman, one of the prime candidates for a Wives of the Great Composers study (others with careers tend to be sopranos, like Pauline Strauss and Nina Grieg). There are two statues she made imagining her husband as a boy, herding geese and cows, in the meanwhile fashioning a pipe from a willow switch. The one pictured below is on the busy road to Nørre-Lyndelse.

Nielsen’s childhood home is beautifully kept, with jugs and vases of wild flowers on the windowsills just as Nielsen recalls his mother arranging, and plentiful objects to complement the rich display in Odense’s Carl Nielsen Museum adjoining the concert hall (a new theatre and opera house is under construction alongside, due to open in 2017 with a cycle of Wagner’s Ring operas). As its curator, singer and Nielsen lover Ida-Marie Vorre, pointed out, it should really be called the Carl and Anne Marie Nielsen Museum, for this beautiful display is equally a homage to Anne Marie’s talent as a sculptor, with plenty of her models and smaller sculptures (pictured above, Anne Marie working on a copy of the Parthenon hydra in Athens during 1903 while Nielsen sits). What a remarkable woman, one of the prime candidates for a Wives of the Great Composers study (others with careers tend to be sopranos, like Pauline Strauss and Nina Grieg). There are two statues she made imagining her husband as a boy, herding geese and cows, in the meanwhile fashioning a pipe from a willow switch. The one pictured below is on the busy road to Nørre-Lyndelse.

In addition the museum has recreations of two rooms in the Nielsens’ apartment on Copenhagen’s Friedriksholms Canal, art and literature playing an equal part alongside music. The knitting objects on display may seem humorously surprising, but have a serious root: after his first heart attack in 1922, Nielsen was forbidden reading or working by his doctor, who suggested knitting as an alternative. At any rate the musical result from around this time was anything but gentle: the Fifth Symphony, which I’m inclined to think is the most energetic and convincingly optimistic of the 20th century.

In addition the museum has recreations of two rooms in the Nielsens’ apartment on Copenhagen’s Friedriksholms Canal, art and literature playing an equal part alongside music. The knitting objects on display may seem humorously surprising, but have a serious root: after his first heart attack in 1922, Nielsen was forbidden reading or working by his doctor, who suggested knitting as an alternative. At any rate the musical result from around this time was anything but gentle: the Fifth Symphony, which I’m inclined to think is the most energetic and convincingly optimistic of the 20th century.

We heard that evening instead the more familiar, and also hugely powerful, Fourth Symphony, with its crucial epigraph explaining the subtitle: “Music is Life, and like it is inextinguishable.” Danish organizations, honoured to have the Vienna Philharmonic and Franz Welser-Möst (pictured below by Knud Erik Jørgenson at the concert) come to their country for the anniversary, actually requested the Third Symphony, since the Fourth was already featuring in several of their own programmes, and were a little dismayed to find the Viennese turning their noses up at that.

A fundamental misunderstanding was revealed by putting it in the first half, with Sibelius’s early Four Lemminkäinen Legends in the second. And misunderstood this “Inextinguishable” was, its outer movements Brucknerised and way too solid, its woodwind Poco allegretto uncharming and lifeless – though there was wonder in hearing the Vienna Philharmonic strings create such a huge impact with the steely two-part writing of the slow movement.

A fundamental misunderstanding was revealed by putting it in the first half, with Sibelius’s early Four Lemminkäinen Legends in the second. And misunderstood this “Inextinguishable” was, its outer movements Brucknerised and way too solid, its woodwind Poco allegretto uncharming and lifeless – though there was wonder in hearing the Vienna Philharmonic strings create such a huge impact with the steely two-part writing of the slow movement.

No matter; it was always going to be curious to hear a rare Austro-German excursion into a symphonist like Sibelius still undervalued south of Denmark. The following evening, after a Festival Hall conversation with Vladimir Ashkenazy, his Icelandic wife and pianist Þórunn said that one comment from a German musician on the Scandinavian greats had always stayed with her: “The music is too deep, too painful for us” (obviously in a different way to Beethoven or Mahler). At least Nielsen is now up there with Sibelius, with no need to prefer the one to the other, and our departure from Copenhagen airport the next afternoon confirmed how valued he is in Scandinavia; by happy chance, the tail-fin of our Norwegian Airlines plane had none other than Denmark’s greatest composer handsomely displayed.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

I was also in Denmark for