Colli, BBCSO, Oramo, Barbican Hall | reviews, news & interviews

Colli, BBCSO, Oramo, Barbican Hall

Colli, BBCSO, Oramo, Barbican Hall

Fresh imagination in Rachmaninov, weird Sibelius and affirmative Nielsen

Was 1911 the best ever year for music?

You don’t engage a pianist who can’t handle the torrents of “the Rach Three”, and we were lucky in the replacement for an indisposed Yevgeny Subdin, young Leeds and Salzburg prizewinner Federico Colli, making his London concerto debut. An inspired one, to say the least. This is an artist who not only plays all the notes but also brings an absolutely individual imagination to what lies behind them. The tempo he set at the start of a work which might well have segued straight out of Sibelius’s fragmentary wood-magic felt a bit held back, and it was clear that Sakari Oramo and the BBC Symphony Orchestra were the ones who would have to keep tabs – which they did with unbelievable clarity and generosity of spirit, right from guest principal bassoonist Amy Harman’s soulful counterpoint to the opening melody; Colli’s self-absorption as he curved around the keyboard, a million miles from the upright, beaming, open-to-the-world attitude of veteran virtuoso Garrick Ohlsson here the other side of Christmas, wasn’t going to give.

Rachmaninov's final peroration was the only point where Oramo let shapely strings dictate the pace

Yet he didn’t have to, with all orchestral colours attuned to his singular vision – and I’ve never noticed the low harmonies of the horns, beautifully led as ever by Nicholas Korth, or indeed other touches in what usually comes across as mere support orchestration, sounding so subtly complementary to the soloist. Colli's vision shouldn’t have worked as well as it did, but somehow the agogic pauses, unusual breaks in phrases and dynamic extremes avoided mannerism and all added up to music with something to say, which isn’t always the case when the concerto is treated like a warhorse.

Colli’s retreat into dreams offered rare metaphysics, but he handled his first big meditation in the slow movement with a boldness that nevertheless brought tears to the eyes, and he managed the cavalcade that leads to the finale’s big tune, so often fudged, with perfect impetus towards a winged poem. Its final peroration was the only point where Oramo let shapely strings dictate the pace, and here at the last hurdle Colli, still in his own world, nearly fell, but they all got to the end in one thrilling piece, justifying a singular and well-paced journey.

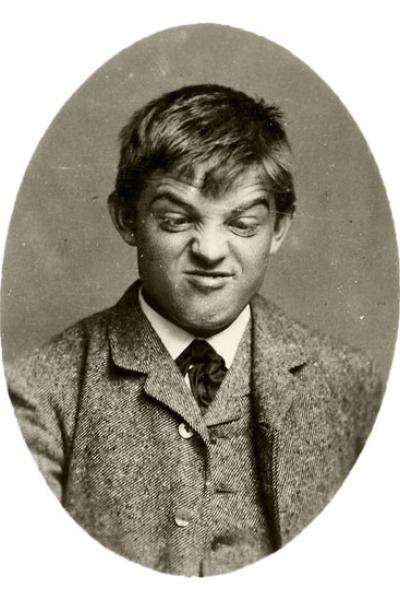

With the Nielsen Third, first major offering of the composer's 150th anniversary year, we stayed out in the fresh air (a younger Nielsen in gurning mood pictured right, courtesy of the Royal Library, Copenhagen). The opening Allegro espansivo in Oramo’s determined interpretation - very loud in this venue, a tad driven, but a style well suited to Nielsen in this mood - flew like an arrow through seismic waves and cosmic merry-go-round waltzes to a triumphant final chord, proud man in all his unstoppable glory.

With the Nielsen Third, first major offering of the composer's 150th anniversary year, we stayed out in the fresh air (a younger Nielsen in gurning mood pictured right, courtesy of the Royal Library, Copenhagen). The opening Allegro espansivo in Oramo’s determined interpretation - very loud in this venue, a tad driven, but a style well suited to Nielsen in this mood - flew like an arrow through seismic waves and cosmic merry-go-round waltzes to a triumphant final chord, proud man in all his unstoppable glory.

Impassive nature launched the Andante pastorale, only to be questioned by melancholy birdsong – flautist Daniel Pailthorpe and oboist Richard Simpson peerlessly personable as ever – and human string responses tore at the heartstrings before we reached the plateau, that radiant summer landscape with wordless soprano and baritone voices (Lucy Hall and Marcus Farnsworth, ecstatic at the back of the platform). Indebted to Wagnerian forest murmurs but somehow more redolent of all that sky you get in Danish landscape paintings, it’s followed by a dynamic wander into the woods, Nielsen’s most puzzling movement structurally; but especially with focused dynamism like Oramo’s, the invention is so strong and its direction so unstoppable that you never question the argument.

There’s not a slack bar in this entire masterpiece, not even in a finale where a big tune, stout and steaky like the parade glories in the comparable movement of Elgar’s Second Symphony – another masterpiece of 1911 which, along with the First, Oramo has championed in Stockholm – seems to say it all straight off, and yet ends up meriting a new and noble key in its typically compact final statement. This Nielsen series is already living up to the even more needful cycle of six Martinů symphonies championed by Oramo’s BBCSO predecessor, Jiří Bělohlávek. Both conductors have already persuaded us that both composers are up there alongside Sibelius, Shostakovich and Vaughan Williams as the towering symphonists of the 20th century, and possibly the greatest masters of affirmative capability, for you couldn’t help but come away from concerts like this feeling better about life.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

Add comment