A decade has passed since Paul Lewis concluded an endeavour of a kind never previously undertaken: to perform, over two and a half years and across four continents, every work Schubert wrote for piano between 1822, the year he was diagnosed with syphilis – ergo, knew he was dying – and his death in 1828.

It was quite an odyssey for those of us who followed those concerts (in my case, across two of those continents), and apparently for Lewis too, as he revisits selections from that programme, adding other, earlier, Schubert sonatas for a scaled-down version of those tours, this time across Britain and Europe, with Asia and North America to follow.

Astride this weekend, London’s Wigmore Hall staged the third, penultimate, programme of the series: two concerts of the same three sonatas, including that which Robert Schumann described as “the most perfect sonata in form and spirit”, in G Major, D894.

Before he set out on the voyage of 2011-2013, Lewis said something revelatory about Schubert, and inconsequentiality in his music. Not for nothing was Schubert the favourite composer of Samuel Beckett, that master of inconsequentiality in literature, and an accomplished amateur pianist.

Lewis put it this way: “We’re all supposed to think that the Viennese classical era produced one tradition of music. But no: Beethoven always seems to find a way through, even to triumph. Schubert never does. He never finds a solution. At least, not after 1822 when he was diagnosed with syphilis. Everything then changes in the music, it becomes so bleak. Beethoven takes you through the shadow of the valley, but there’s resolution in the end. Schubert not so – he takes you on a journey, and leaves you nowhere”.

He added: “The musician knows he can never really get to the bottom of a piece, because if you did, why bother carrying on?”. “Fail again, fail better”, wrote Beckett. That kind of humility before the music is a very good place to start.

A call not so much of the wild - though there is that too, in the development section’s turbulent interruptions - but of some state of mind and soul that is precious, but glimpsed rather than attainable

These Wigmore concerts began before Schubert’s calamitous diagnosis – in 1817, with the then 20-year-old’s Sonata in A Minor, D537. Schubert was enamoured by Beethoven to the point of obsession but not possession: this is a push forward, in its way, from classical to romantic. Not without its heroic moments, but in the opening Allegro, Lewis seems to rejoice in Schubert’s casting off the initial swagger and tonal stability with dissonance and shifts in key, pointing a way forward through the coming sonatas, and the evening. Even the final chord has ambivalent dissonance.

In the collage of the ensuing Allegretto, after a meditative opening, there’s downright weirdness in the nursery-rhyme, tin-soldier tune and repeated notes on right hand; sparse melody which fills out into a middle passage with dark undertones, prescient of what is to come.

The piece ends with an Allegro vivace, Lewis giving the scales an upward surge, and echoed downward trickle, for contrast and uncertainty of mood, even in this young music. There are songs that cannot quite conclude, questions and attempts at answers across the keyboard.

Likewise in the Sonata in B, D575, which Lewis plays as testimony to Schubert’s eagerness to experiment, with modulations full of surprises, and exchanges between lyricism and dramatic outburst. In Monday’s second concert, the contrasts cut deeper; there was real mischief in the Scherzo.

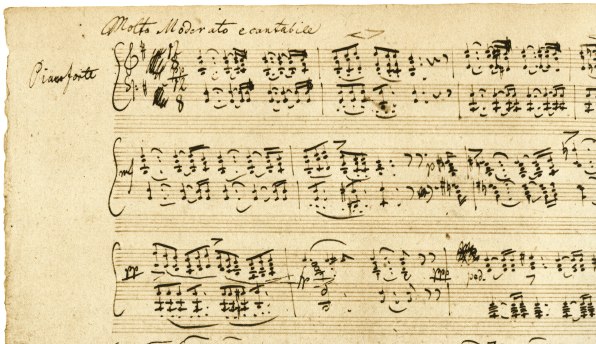

Schumann was right about the perfection of the G Major Sonata (manuscipt first page pictured right), written in October 1826, two years before Schubert died, aged 31. (I confess to including Lewis’s account of the work as the core of my "Private Passions" on Radio 3 in 2018.)

Schumann was right about the perfection of the G Major Sonata (manuscipt first page pictured right), written in October 1826, two years before Schubert died, aged 31. (I confess to including Lewis’s account of the work as the core of my "Private Passions" on Radio 3 in 2018.)

Of course music changes when one is aware of imminent mortality, and Schubert’s late, beloved but terrifying sonatas balance reflection and foreboding with a poignancy that makes them among the greatest pieces ever written for the instrument. But the "perfection" of D894 is in many ways like an island in that tempestuous sea of music; it has dream-like radiance, and serenity – almost.

This is not a matter of key: the sonata was written soon after the String Quartet D887, also in G Major, but altogether darker. It was initially published, after Schubert’s death, as a ‘Fantasie’, and the notes to Lewis’s Harmonia Mundi recording describe it as such, though not the concert programme. And perhaps that’s what it is, as Lewis plays it: a fantastical, elusive solace on which the endurance of tribulation and expectation of death hang.

On both nights, Lewis prepared to play as though for some pagan rite. The opening rumination – lyrically simple but immediately arresting – is profoundly serene, yet the piece seems to find its way forward on precarious tip-toe as it rises, beautiful but unassured, into the minor key.

Indeed, another difference between Lewis’s acclaimed Beethoven and his Schubert is the way the latter seems often to navigate uncharted terrain, without a grand design, so that the oft-described ‘serenity’ of this movement – and those to come – is laced with yearning for something beyond it. A call not so much of the wild – though there is that too, in the development section’s turbulent interruptions – but of some state of mind and soul that is precious, but glimpsed rather than attainable. The movement is marked ‘Molto moderato e cantabile’, and Lewis takes Schubert at his word: there is song in these inimitably exquisite – inimitably Schubertian – melodies and tunes.

Lewis plays the final three movements as an uninterrupted tapestry of sonorities, reflections, contrasts, colours and moods.

The opening of the Andante is deceptively tranquil. Again, it seems to pick its way forward: it doubts, then proceeds, and doubts again: percussive outbursts punctuate the sway of the eerily lyrical, rocking motif that connects the movement, appearing, disappearing and reappearing – which Lewis endows with a mellifluous beauty. There’s a dialectic: an ebb and flow, not just between percussive and lyrical, but between dubiety and hope, uncertainty and affirmation, disturbance and peace, until the original mood of conciliation is restored.

The Menuetto, to which Lewis gives poise as well as moments of drama, opens with flair, before giving way to the reflective trio section, played with crystalline clarity and intimacy - again this beautiful lilt and inflection. Then back to the more percussive opening music – it’s a not-quite-dance, as though diagonally observed, rather than partaken in.

Joy – or at least attestation – in late Schubert is poignantly defiant, and this is what happens in the Allegretto. Lewis seems (whether he actually does or not) to stretch the tempi, this tidal crosscurrent: modulations that seem to hold themselves back, then proceed. And when they do, the music insists, with almost a hop-skip-and-jump, even the chime of bells, energetic, and framing the more meditative, fluid moments of deceleration. There’s reaching out for affirmation, and it is there, in the quietened conclusion, for one of those rare moments in the late sonatas. But affirmation of what? True to Lewis’ remark of a decade ago, we have no answer apart from a deeper understanding of the romantic imagination.

Joy – or at least attestation – in late Schubert is poignantly defiant, and this is what happens in the Allegretto. Lewis seems (whether he actually does or not) to stretch the tempi, this tidal crosscurrent: modulations that seem to hold themselves back, then proceed. And when they do, the music insists, with almost a hop-skip-and-jump, even the chime of bells, energetic, and framing the more meditative, fluid moments of deceleration. There’s reaching out for affirmation, and it is there, in the quietened conclusion, for one of those rare moments in the late sonatas. But affirmation of what? True to Lewis’ remark of a decade ago, we have no answer apart from a deeper understanding of the romantic imagination.

Lewis insists on musical modesty, inasmuch as he places himself – as he often explains – at the service of the composer. He talks about “getting the message across”, as the main task of sonority and technique. “It’s not about me”, he said on the eve of those world tours in 2011-13, “it’s about the composer and the music, the message of the music, the feelings and emotions it’s trying to convey. The music is more important than me – Schubert is much more important than me”. His work is to try and understand what is happening in the creative imagination of the artist, and to convey it.

And this is exactly what happened at these concerts – and what has enriched, and will no doubt enrich, others in the series. After the visions of 20-year-old Schubert in the first half, we are admitted into the intimate confessions of a romantic. For this is nothing if not ‘romantic’ music now, not as glib definition but a matter of struggle, restive spirit and the quest for both peace of mind, and the beyond.

Lewis’s Schubert is about essence and sublimity. Words cannot describe the sublime but we have to try, and might as well leave it to the experts: we are transported to a terrain described 18 years earlier that D894 by William Wordsworth as “something far more deeply interfused / Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns”. Two decades later, in 1847, Emily Bronte would use the metaphor of the moor beyond the garden wall. We are invited to consider humanity’s inner and outer relationships to these things, and our death before their infinity, which in Schubert become intensely personal. And without consequence, though it is what it is.

No two snowflakes are the same, and the second concert of the same programme on Monday night contrasted with that on Saturday. There was more propulsion, less hesitation. Even the contortions of Lewis’ expressions while playing were a measure of the commitment. The younger pieces were brought forward, somehow. The quirkiness in the Allegretto of D537 was even quirkier, the strangeness of the Allegro even stranger.

The ‘perfect’ G Major had solemnity to it, for which it was no darker, but felt more pensive. The lyrical passages were like waterfalls: the Allegretto had an aqueous flow, before finding almost a gallop.The latter two passages especially were more expansive.

The audience inevitably makes a difference. Monday’s crowd was more palpably engaged – enthralled, even – than that sometimes blasé, entitled Wigmore public.  Inevitably, one thinks back to the epic cycle spanning the years 2011-2013. Lewis wrote for The Arts Desk after the Covid-19 lockdown: “ You may have played a piece for 30 years and think you know it well, but if it’s truly great music, you’ll come back to it and see something you didn’t find last time”. Now, after Monday's concert, he reflects: “It’s hard to put your finger on what has changed since however it felt 12 years ago. As one gets older, the space in the music gets bigger. The space Schubert inhabits, in a way. When I was younger, perhaps I thought: we have to show something, to create things with the music. But now, I just trust Schubert; I feel that I do less, and Schubert does more. I don’t have to influence anything, I just let Schubert do it.”

Inevitably, one thinks back to the epic cycle spanning the years 2011-2013. Lewis wrote for The Arts Desk after the Covid-19 lockdown: “ You may have played a piece for 30 years and think you know it well, but if it’s truly great music, you’ll come back to it and see something you didn’t find last time”. Now, after Monday's concert, he reflects: “It’s hard to put your finger on what has changed since however it felt 12 years ago. As one gets older, the space in the music gets bigger. The space Schubert inhabits, in a way. When I was younger, perhaps I thought: we have to show something, to create things with the music. But now, I just trust Schubert; I feel that I do less, and Schubert does more. I don’t have to influence anything, I just let Schubert do it.”

I suggest that this relates to the original idea of navigating without a map, and – ultimately – inconsequentiality. Lewis replies by returning to the original point and citing his teacher and mentor to a degree, Alfred Brendel: “Brendel used to say that Schubert proceeds with the assurance of a sleep-walker. Look, Beethoven knew exactly where he was going. With Schubert, it’s the opposite. Is ‘irresolution’ a word? If not it should be. Because that’s what this is, and what makes it so human. We don’t have the answers, do we?”

In this way, then as now, Lewis establishes himself, I posit, as the world’s most compelling interpreter of Schubert piano music of his generation. Lewis’s Schubert is existentially cogent as well as musically illuminating. This D894 sonata is the composer’s most radiant and lyrical, but from Lewis’s keyboard, that radiance is only too aware of its own shadow.

Add comment