“I am always fascinated by how much is in a voice, by their textures and qualities,” says composer Jocelyn Pook. “They’re like aural photographs of a person and you recognise them instantly.” We are in her studio in north London and Pook flicks through audio-files in her computer to prove the point. Some of the voices she was chosen for their inherent musicality – voices on answerphones rise upwards as questions are asked and intervals are sounded for multi-syllabic words. Pook, an award-winning musician who often uses voices and vocal rhythms – real, sampled and digitally pitchshifted – in her compositions, is fascinated by the creative possibilities that the human voice affords.

But what happens when the voices prove untrustworthy? Hearing Voices, Pook’s extraordinarily intimate new song cycle, which receives its world premiere at the Southbank tomorrow night, tackles that question head on. Commissioned by the BBC Concert Orchestra, Hearing Voices is one of five works relating, loosely, to mental health and psychic productions, within the evening’s H7steria event and the programme works by Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, Schoenberg and an arrangement of a song by the rock group Muse. Scored for orchestra, taped voices and singer Melanie Pappenheim, the mezzo soprano who is a fixture in Pook’s compositions, Hearing Voices is based around an aural sleight of hand: it makes audible the internalised voices that people keep to themselves. Pook’s song cycle is about madness and the experiences of five separate women with hearing voices, but beyond that, it’s specifically about feminine madness and about the arena in which madness is presented and constrained.

The hugely responsive music supports the stories themselves – not necessarily sweetly

What makes Hearing Voices so personal to the composer is that, out of the five real-life women in the song cycle speaking of their experiences of madness, four are known to Pook and two – her great-aunt Phyllis Williams and her mother, Mary Cecil Pook, who died last year – are close relatives. Mary, along with artists Bobby Baker (whom Pook has worked with several times in the past) and Julie McNamara are present in the forms of recorded interviews that Pook conducted with them. There is only one historical character – Agnes Richter, a German seamstress, who was in a state asylum for many years in the early 20th century. While there, Richter made a jacket from the rags of hospital uniforms and it was onto the jacket’s every available surface that she embroidered messages. “It’s covered with text, some of it decipherable, some of it not,” Pook says. While some words attributed to Richter in Hearing Voices are the product of dramaturge Emma Bernard, Pook uses many phrases that are Agnes’ own: "I plunge headlong into disaster” is one of these that Pook has set to music.

“The writing interested me greatly, it’s a real theme in mental illness,” Pook says. “I think it’s partly writing in protest and partly writing as the need to make some sense of what is happening to you.” The survival of the jacket is down to its inclusion in the collection of outsider art created by psychiatrist and art historian Hans Prinzhorn; and Pook first came across it in a groundbreaking book, Agnes’s Jacket: A Psychologist’s Search for the Meanings of Madness, by American academic Gail Hornstein. While Hornstein’s account of the jacket and its hidden meanings was certainly a powerful spur to the writing of Hearing Voices, Pook’s inspiration came from of her own family and great-aunt Phyllis, who was in an institution for 25 years, in particular.

“The writing interested me greatly, it’s a real theme in mental illness,” Pook says. “I think it’s partly writing in protest and partly writing as the need to make some sense of what is happening to you.” The survival of the jacket is down to its inclusion in the collection of outsider art created by psychiatrist and art historian Hans Prinzhorn; and Pook first came across it in a groundbreaking book, Agnes’s Jacket: A Psychologist’s Search for the Meanings of Madness, by American academic Gail Hornstein. While Hornstein’s account of the jacket and its hidden meanings was certainly a powerful spur to the writing of Hearing Voices, Pook’s inspiration came from of her own family and great-aunt Phyllis, who was in an institution for 25 years, in particular.

"Phyllis came from a very conventional army family in the Channel Islands,” says Pook, handing me a photograph taken in the 1900s. It shows a young woman surrounded by a family of boys and men. She went to finishing school in Switzerland, moved to Italy between the wars and in the Thirties moved to London. It was there, in a small flat in Notting Hill Gate, that her breakdown began. Phyllis heard voices: at first they were benign. “I ask myself, is it the thought I hear or are they speaking out loud?” she wrote in her diaries, which Pook and her mother received after Phyllis’s death. “There seems to a regular company of people surrounding me all the time so I cannot complain of loneliness,” Phyllis recorded on 24 December 1934. Within days, the tenor of the voices has changed and the writings are becoming agitated. She is called an “accidental woman” and the voices are ordering her to starve herself to death. By 6 January 1935, Phyllis is writing about outcasts, lepers and her “separation from God”. The voices are so loud and incessant she has trouble recording them. Pook says: “I end it with Phyllis with her hands over her ears and singing a hymn to try to block the voices out.”

Making manifest what Phyllis – and others – who have similarly suffered is significant in Hearing Voices. One theme that runs though it is shame: the families of both Phyllis and Mary were horrified by the breakdowns. When Mary (under the pseudonym of Mary Cecil) published, in the late Fifties, In Two Minds, a thinly disguised memoir of her own nervous breakdown and coma-inducing deep insulin treatment, her relatives were appalled by the exposure. To underline an unwillingness to collude in such silence, one section of Hearing Voices consists of scored lists of words aimed at the ‘mad’: “You’re mad! Insane! You silly girl! Nutter!”

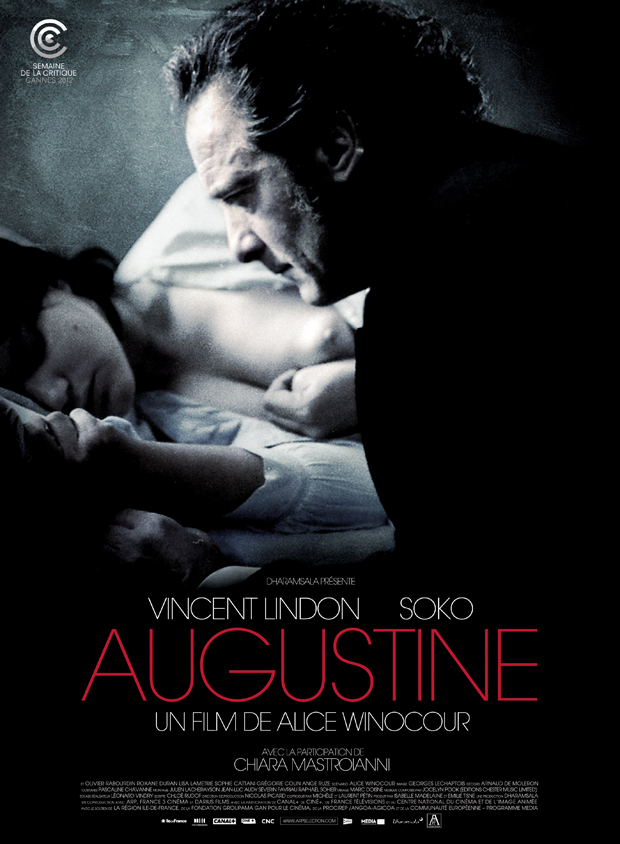

Pook, a viola player who began composing – often for small theatre ensembles and her own group, Electra Strings – soon after graduating from London’s Guildhall School of Music and Drama in 1983, learned early in her professional life the importance of structuring a musical story properly. The people in Hearing Voices do have their own musical motifs, but these are not hammered home. Dominated by a bedrock of stringed instruments which provide a foundation for the rest of the score, it often feels that the hugely responsive music supports the stories themselves – not necessarily sweetly, but it underlines time and again the experiences being shared with us. It is a technique she replicates in her score for film director Alice Winocour’s Augustine (pictured left), a drama set in 1873 in the Parisian Salpêtrière asylum, where Charcot gave theatrical displays of female hysterics to visiting physicians (Freud among them). “In Augustine, the music is very much about the inner world, about emotions and sadness,” Pook says. “It doesn’t need to be illustrative and explosive.”

Pook, a viola player who began composing – often for small theatre ensembles and her own group, Electra Strings – soon after graduating from London’s Guildhall School of Music and Drama in 1983, learned early in her professional life the importance of structuring a musical story properly. The people in Hearing Voices do have their own musical motifs, but these are not hammered home. Dominated by a bedrock of stringed instruments which provide a foundation for the rest of the score, it often feels that the hugely responsive music supports the stories themselves – not necessarily sweetly, but it underlines time and again the experiences being shared with us. It is a technique she replicates in her score for film director Alice Winocour’s Augustine (pictured left), a drama set in 1873 in the Parisian Salpêtrière asylum, where Charcot gave theatrical displays of female hysterics to visiting physicians (Freud among them). “In Augustine, the music is very much about the inner world, about emotions and sadness,” Pook says. “It doesn’t need to be illustrative and explosive.”

Sampled voices play a significant part in Pook’s orchestration and she speaks of how using recorded voices opened up for her a new way of approaching musical creation. “Gavin Bryars did this with Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet,” says Pook, also citing such early Steve Reich works such as Come Out and It’s Gonna Rain and artist Graeme Miller’s Dungeness Project: The Desert in the Garden. “But the person who also did it and way ahead of his time too was Holger Czukay, who had been in [German experimental rock band] Can. His "Persian Love" [from 1979] took part of an Iranian song he’d heard on the radio,” she says. “It was amazing, absolutely ahead of his time. It also introduced me to Persian singing voices, which I have used a lot.”

Many of the texts produced by Pook’s "mad" women contain references to sound, making them a gift of sorts to a composer. Bobby Baker, for example, speaks in a moving section, about the “winds of the devil sweeping [her] along” and Julie McNamara recalls voices screaming at her constantly. Pook’s handled her material respectfully – commendably so, considering the closeness of some it to her own life. (And it must be said that Mary’s account of being possessed by the devil is hilarious and brave and incredible simultaneously. On stage, Mary’s visions of seeing writing in the air will be rendered by Pook’s artist husband Dragan Aleksic.) While there can be a macabre humour present – many of Pook’s interviewees yield up an incredulous laughter and Pook’s sampled it to make laughing refrains – there are no attempts to characterise the experiences of the women in simple compositional terms. “The voices do not dictate the music,” Pook says definitely. “Sometimes the phrase dictates the key, such is in the section where the orchestra picks up the tune of the laughter – and the laughter is quite simply about survival.”

- Jocelyn Pook’s Hearing Voices receives its world premiere with the BBC Concert Orchestra on 3 December 2012 at the Queen Elizabeth Hall, London, as part of the H7steria programme

- DESH is out now on Pook Music

Listen to part of Pook's score for Kubrick's Eyes Wide Shut

Add comment