Music and visual art, at least at the highest level, should go their own separate ways; put them together, and one form will always be subordinate to the other. A composer being inspired by an artist's work, or vice versa, is something else altogether.

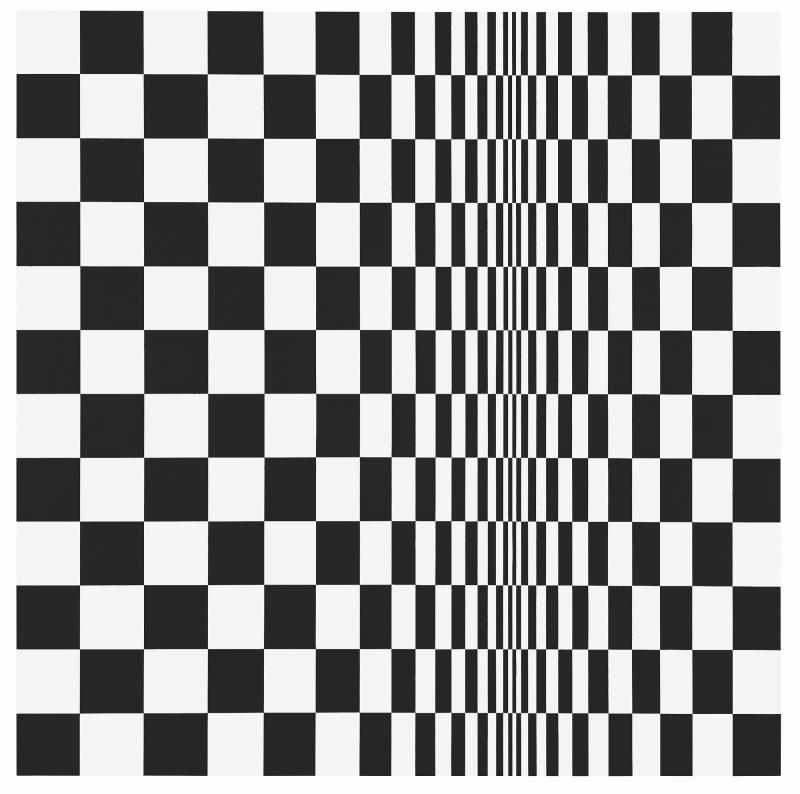

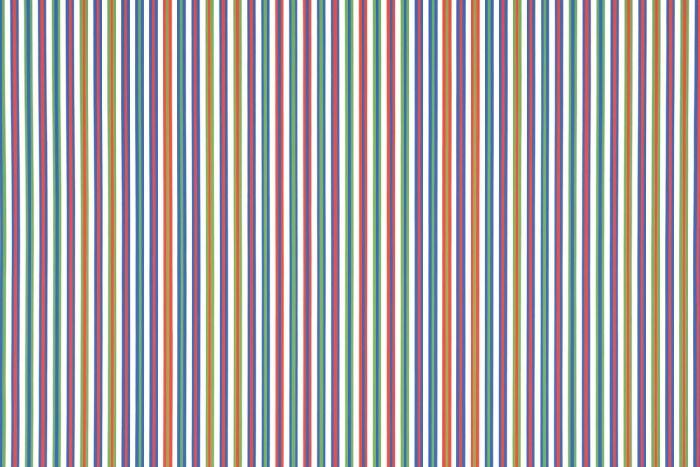

Any comparison will only be analogous – interestingly, Riley gives musical titles like "Paean" and "Aubade" to some of her works – but they do share much in common. In neither is the abstraction bloodless, static or merely intellectual (Riley broke the mould with what she called "conscious intuition" in the op art of the 1960s without study of optics or deeper knowledge of mathematics). Shapes shift in the vortex, surface busy-ness may yield to calms at the eye of the storm, response can be surprising – the difference between the two being that, as you spend time looking at a Riley, the point of greatest intensity can be anywhere within the experience, while in Haas' canvas the frissons are fixed in time by the composer. What Haas (pictured below by GM Castelberg) says in the short film we saw before the performance, “it seems to be repetitive, but it is not," is equally true of his music, where microtones merely increase the expressive possibilities.  And the work is full of colour, which you might paradoxically say of Riley’s earlier black and white assaults on the optic nerve. Even so, I’m not sure I would have chosen the celebrated Movement in Squares of 1961 (pictured below) as the image to show before – praise be, not during – the performance; though music evokes a different kind of “hearing picture” to any one of the canvases I’d just seen, there would have to be a wide colour palette as equivalent to the Hommage. Nevertheless, Riley’s generalisation of a parallel painting as “repose, disturbance and repose” might be turned inside out to describe Haas’s piece. It starts with buzzing strings at extremes of the register; Haas is not so cruel as to make them play constantly like this for 40 minutes, so fixed sounds emerge; piano and tuned percussion lead in evoking triads, tritones, whole-tone scales which morph very quickly into something else.

And the work is full of colour, which you might paradoxically say of Riley’s earlier black and white assaults on the optic nerve. Even so, I’m not sure I would have chosen the celebrated Movement in Squares of 1961 (pictured below) as the image to show before – praise be, not during – the performance; though music evokes a different kind of “hearing picture” to any one of the canvases I’d just seen, there would have to be a wide colour palette as equivalent to the Hommage. Nevertheless, Riley’s generalisation of a parallel painting as “repose, disturbance and repose” might be turned inside out to describe Haas’s piece. It starts with buzzing strings at extremes of the register; Haas is not so cruel as to make them play constantly like this for 40 minutes, so fixed sounds emerge; piano and tuned percussion lead in evoking triads, tritones, whole-tone scales which morph very quickly into something else.  The playing itself, like Haas’s score, was quietly miraculous in that there were hardly any jagged edges, and sequences which felt like gliding over shifting patterns in water: beautiful, limpid, evanescent. Full credit to conductor Brad Lubman, warmly applauded by the instrumentalists, for making it all seem effortless, and of course to the London Sinfonietta for commissioning the work alongside Southbank Centre and Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival. In a generous gesture, Haas had been asked to recommend a work by a student of his at Columbia University; Katherine Balch’s New Geometry; but this was a baffling preface in which you could only sense the irregular forms, not the geometry within: remarkable, all the same, for passages on the cusp of audibility, especially in the playing of trombonist Byron Fulcher. There was also a post-interval screening of film responses to Riley and Haas from students of Central Saint Martins; but it made more sense to leave with the sensuality of the main artist and composer still resonating.

The playing itself, like Haas’s score, was quietly miraculous in that there were hardly any jagged edges, and sequences which felt like gliding over shifting patterns in water: beautiful, limpid, evanescent. Full credit to conductor Brad Lubman, warmly applauded by the instrumentalists, for making it all seem effortless, and of course to the London Sinfonietta for commissioning the work alongside Southbank Centre and Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival. In a generous gesture, Haas had been asked to recommend a work by a student of his at Columbia University; Katherine Balch’s New Geometry; but this was a baffling preface in which you could only sense the irregular forms, not the geometry within: remarkable, all the same, for passages on the cusp of audibility, especially in the playing of trombonist Byron Fulcher. There was also a post-interval screening of film responses to Riley and Haas from students of Central Saint Martins; but it made more sense to leave with the sensuality of the main artist and composer still resonating.

Add comment