Hans Werner Henze, the composer who died on Saturday aged 86, wrote the music for one of Margot Fonteyn's signature ballets, Ondine, a ballet about an inhuman spirit who longs to be joined to a man - but when she does, he must die. It might almost be a metaphor for the death of the thought the moment it is realised.

A 1958 collaboration with Britain's major choreographer Frederick Ashton, Ondine was the first full-length ballet score to be commissioned by the emerging Royal Ballet, and it was, for the very young, and creatively fluctuating Henze, a process that confirmed his instinct that music theatre was an extraordinary world of its own, speaking emotive languages to audiences that went beyond music alone. He would go on to make some of his most consistent successes with opera, but Ondine - though it took time to be accepted - is now championed as one of the most fascinating and elusive danceworks of the 20th century.

With Fonteyn as the treacherous water-nymph who falls fatally in love with a mortal man, the work tested the British ballet world's inherent conservatism in the Fifties. The music was written to summon pictures of the sea in all its moods, rather than spin melodies, and both Ashton and Fonteyn had many difficulties interpreting via their balletic expectations an essentially Romantic story in a post-Stravinsky music style from the 20th century.

For what made the whole thing happen was a night of cutting-edge ballet in Hamburg, with Ashton himself stretched to his most modernist in his glitteringly mysterious masterpiece Scènes de ballet, choreographed to Stravinsky's music. For the student composer sitting in the audience, it was a creative birth, as well as the start of a close and lifelong relationship with Ashton. When they collaborated on Ondine for the Royal Ballet a decade later, Henze and Ashton found themselves coming at the same subject - mythic fantasy - from different angles, yet this generated a stage creation of utmost imagination and profound thought, as extracts from the biographies of Ashton and Fonteyn below narrate.

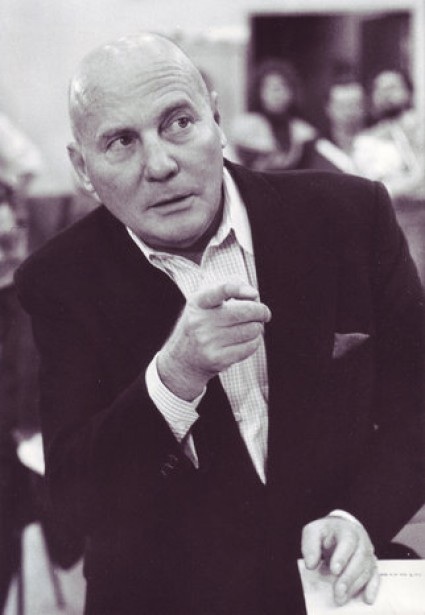

In 1991 Henze (pictured below, © Kranichphoto) told me in an interview for the Sunday Telegraph about his "night to remember":

I was 22 and already a composer when Sadler's Wells Ballet came to Hamburg in the autumn of 1948 to perform for a week to the German public. The festival started with Frederick Ashton's new Scènes de ballet, to Stravinsky's score.

I was 22 and already a composer when Sadler's Wells Ballet came to Hamburg in the autumn of 1948 to perform for a week to the German public. The festival started with Frederick Ashton's new Scènes de ballet, to Stravinsky's score.

I had never heard this music before, and I had never before seen classical ballet in the hands of a modern choreographer. This union between choreography and music showed me that one could achieve classicism in music and music theatre without having to be exclusively retrospective. I even made a piano score of another Stravinsky ballet so as to learn his style thoroughly, and a lot of harmonic thinking of that kind went into my own writing.

The unnaturalness - which is where art starts - seemed like a sign from a more attractive and interesting artistic world

That night a new world of aesthetics opened up to me. It was neither Ashton nor Stravinsky, but the fusion of the two: the elegance of Ashton's answers to the score, the elegance of the moves, and the fact that he gave meaning to a pirouette, to a grand jeté. These classical steps suddenly became something new; put into context, they changed or deepened their own meaning and that of the music as well.

I have to take the novelty of the experience into account, because I'd only seen German modern dance before, and had always thought dance was slightly silly. But that feeling vanished on this occasion. The artificiality of ballet, the unnaturalness - which is where art starts - seemed to me like a sign from a more attractive and interesting artistic world than the one I knew.

I wrote to Ashton later about it, and he answered me with a kind letter. After seeing Scènes I wrote a lot of ballet music and had it recorded privately (there were no tape recorders then), and I sent the discs to him. Some years later he commissioned me to write the ballet Ondine for him.

The Commission

from David Vaughan's biography, Frederick Ashton and his ballets (1977, Dance Books)

[Walton was Ashton's original thought, but he was too busy and suggested Henze.] Henze accepted the commission and he and Ashton went to Italy together to discuss the project. Ashton read the libretti of two 19th-century ballets based on the story, Jules Perrot's Ondine; ou la Naïade, and Paul Taglioni's Coralia, but decided to base his own on the original novel by Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, retaining only the idea for the pas de l'ombre [the Shadow dance] from Perrot's version… As was his habit, Ashton drew up a detailed minutage for the guidance of Henze…

Ashton would often ask him anxiously, 'Have you heard a tune today?'

Henze came to London early in 1957 to begin work, and stayed in Alexander Grant's house, where there was a piano; Grant recalls that Ashton would often ask him anxiously, 'Have you heard a tune today?' When rehearsals began Ashton worked in the usual way with a pianist but soon found the piano reduction unsatisfactory, so he asked Henze to have a recording made of the full score. This was done by a German orchestra under Robert Irving's direction, and after that Ashton rehearsed to a tape, finding that he had to throw out most of what he had already set…

Modification of the scenario continued as a result of discussions held in the rehearsal room between Ashton and the principals. 'Sometimes,' said Fonteyn in an interview with Peter Brinson, 'Henze's score… just didn't seem to say the same thing as the scenario. Take, for example, the little mime scene about Palemon's heart in the first act. Ondine comes out of the water. Palemon sees her and loves her. After this, in the original version, Ondine was attracted by Palemon's amulet and snatched it away. When he took it back she became petulant and angry.

'But when we did that scene it seemed false, especially musically. So now Ondine replaces the amulet round Palemon's neck because she is newly interested in him rather than the amulet. At that moment he presses her hand to his heart. She is frightened by his heartbeat (ondines don't have hearts, you know) and jumps back with surprise. Then, overcome by curiosity, she puts her hand over his heart to feel it beat again.'…

The Dancer and the Music

From Meredith Daneman's biography, Margot Fonteyn (2004, Viking)

Ever since Scènes de Ballet had been shown in Berlin in 1948, Henze and Ashton had sustained a heightened correspondence of the passionate yet sublimated sort which steams towards artistic collaboration: 'To me,' wrote Ashton, 'you are Berlin & the whole charm of Germany - your blondness, your sentiment, your forthcoming warmth.' For his own part, Henze extols Ashton's 'sense of elegance in human relationships… He was for me like a rope to climb up from the sea.'

Ever since Scènes de Ballet had been shown in Berlin in 1948, Henze and Ashton had sustained a heightened correspondence of the passionate yet sublimated sort which steams towards artistic collaboration: 'To me,' wrote Ashton, 'you are Berlin & the whole charm of Germany - your blondness, your sentiment, your forthcoming warmth.' For his own part, Henze extols Ashton's 'sense of elegance in human relationships… He was for me like a rope to climb up from the sea.'

[Henze recalled:] 'A decision was taken that did not go in the direction the music went. The amount of discrepancy did to become obvious until the last rehearsals. The first act I wrote in Battersea and the rest at home in Naples, but by then the style had been established. It had become a kind of ritual that Freddie would come to Battersea in the evening and listen to what I had done int he daytime, and then we would go over to Yeoman's Row and have some kind of dinner in the basement - Alexander Grant usually being present - and Freddie would criticise what I had done. Boxing me, hitting me, saying: "Give me a tune - I want a tune." He didn't recognise my tunes. The score is very tuneful.'

Time has proved the composer right: the score of Ondine is perfectly accessible to us now. But either Margot was as deaf to its melodies as Ashton, or she had been conditioned by the choreographer's reactionism. Certainly Henze found Ashton alarmingly possessive of his ballerina: 'I think she was kept away from me, like a secret I wasn't quite up to. She had difficulties with the music which, for a year or so, was from the piano score - a very insufficient informer of what is going on in terms of colours, rhythms, counterpoints, all that. And so Margot, it seems, was saying: "I can't hear it, I can't hear it." I would have rushed to London and explained the music myself and played it to them, but I was never asked. in the end I found a sympathetic orchestra and recorded it from beginning to end, and the dancers worked from the tape. I had the impression she didn't want me to come nearer than I was.'…

Ondine was Ashton's 'Fonteyn-concerto', and she (according to Henze) 'his violin'.

Pictured above: Fonteyn as Ondine, credit Roger Wood Collection/Royal Opera House

The Choreographer and the Composer

From Julie Kavanagh's biography of Frederick Ashton, Secret Muses (1996, Faber & Faber)

On a warm August night in 1956 W H Auden and Chester Kallman were having dinner in the piazza of Forio, Ischia. Ashton sat at a table near by, in earnest conference with the 30-year-old composer Hans Werner Henze. It was at Maria's Café, the focal point of the village, that the first discussions about their ballet, Ondine, took place... Although he and Ashton would sometimes join Auden's table that summer, they did not ask him for advice about the libretto. 'We didn't even tell them what we were doing,' said Henze. 'Fred didn't want to be influenced by Auden who might have dissuaded us from doing this as a ballet. He was probably terrified of his authority.'

On a warm August night in 1956 W H Auden and Chester Kallman were having dinner in the piazza of Forio, Ischia. Ashton sat at a table near by, in earnest conference with the 30-year-old composer Hans Werner Henze. It was at Maria's Café, the focal point of the village, that the first discussions about their ballet, Ondine, took place... Although he and Ashton would sometimes join Auden's table that summer, they did not ask him for advice about the libretto. 'We didn't even tell them what we were doing,' said Henze. 'Fred didn't want to be influenced by Auden who might have dissuaded us from doing this as a ballet. He was probably terrified of his authority.'

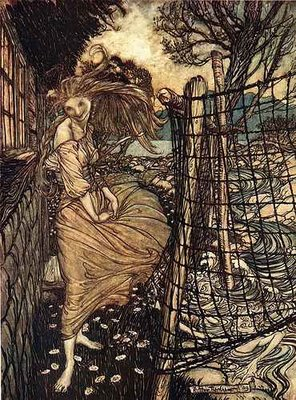

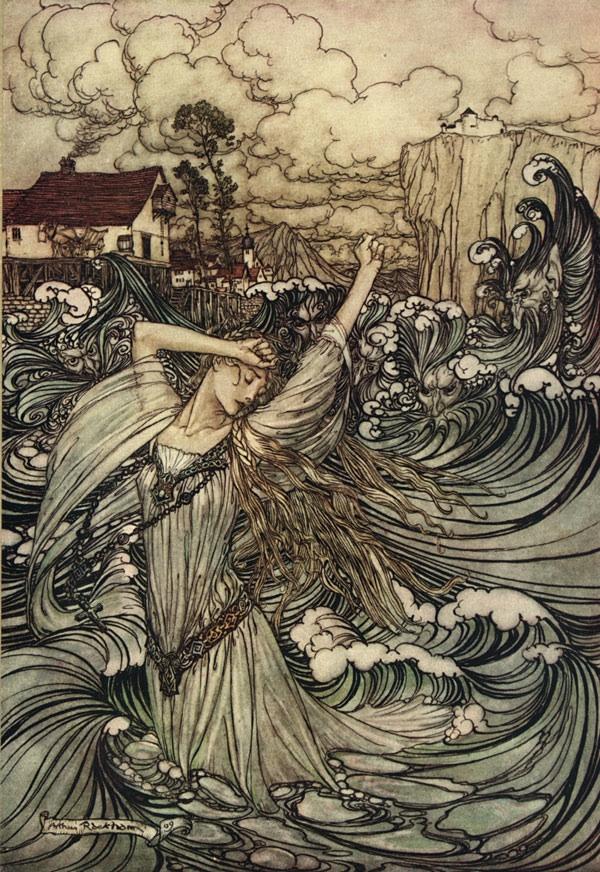

Their conversations continued on the beach, Ashton's copy of de la Motte Fouqué's Undine (a 1909 edition, with illustrations by Arthur Rackham, picture left) becoming sandier and more sun-curled by the day. '"What is Ondine? Who is Ondine?" we asked ourselves.

William Walton is generally assumed to have been Ashton's first choice of composer for Ondine. "William was busy with something else, but always one to do a favour to a pal, he suggested Hans Henze," said his widow, Susana Walton. 'The establishment at Covent Garden were not inclined to engage a fairly unknown composer, and so it was a question of William forcing David Webster to accept this.' Henze however insists that this was not the case: the Waltons were his neighbours on Ischia and they saw each other almost every day. 'They would have told me.'…"

The letter he wrote on his return to London is full of bitter-sweet regret about an affair that was 'not to be'

[After seeing Ashton's Scènes de ballet in 1948, Henze "wrote Ashton a fan letter, the first of many to come…" After getting an encouraging reply, Henze then wrote a 20-minute ballet, Ballett-Variations, and sent it to Ashton.]

In the autumn of 1952, when the company performed in West Berlin, Henze was able to play his music to Ashton. They spent only a few days in each other's company, going to parties and to the theatre, a period in which they developed an intense and lasting affection for each other. 'How strange the way our love & sympathy grew,' Ashton later recalled. He was immediately drawn to Henze, investing him with the kind of 1930s Sonnekind attributes extolled by Isherwood and Spender… The letter he wrote on his return to London is full of bitter-sweet regret about an affair that was 'not to be'. 'I loved you & had it not been that I knew & respected your other ties & against which I could not compete - I would have asked you to accept my love…'

[Henze replied:] 'The situation between us is really a beautiful one, and friendships like ours can become important and eternal and marvellous, especially if they are not melanged with what one calls "an affair".'

Tamara Rojo talks about dancing Ondine in a Royal Ballet trailer

Add comment