It sounded a dry subject and a dry title for Alan Bennett’s first play for five years - a fictional meeting between composer Benjamin Britten and poet W H Auden 25 years after they fell out, two old buggers, one furtive, the other extrovert. But at last night's premiere The Habit of Art proved an excruciatingly funny play, ribald, merciless, and as much about the bad habit of Theatre as that of the higher-toned Art. Nicholas Hytner has given it a wildly enjoyable production at the National Theatre that fields some epic comic performances in a bravura script.

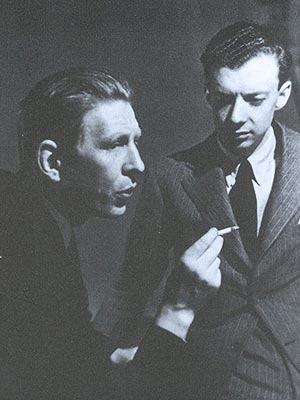

Wystan Auden was “in the imperative”, as his housemaster said of him at school, an ugly, enchanting, slovenly bully. Early on he and Britten, the golden boys of British poetry and music (pictured below), collaborated on the opera Paul Bunyan and the Ballad of Heroes, but fell out when the flamboyantly queer Auden criticised Britten for being too clean, too “healthy”, too in denial of his nature. A quarter of a century later, Oxford's former Professor of Poetry has nothing to write, is bored with retelling his old successes, has gross lavatory habits, and hires rent-boys - his servants call him Professor of knobs in gobs.

Yet The Habit of Art is so onion-layered that it prompts you to question whose Auden this is that we’re seeing - Auden’s Auden, Britten's Auden? Bennett’s Auden, the biographers’ Auden? The set-up is that a new play, called "Caliban’s Day", is being rehearsed at the National Theatre itself about Britten and Auden’s reunion in 1972, and the unimpeachable Alex Jennings and Richard Griffiths play Henry and Fitz, actors cast as the two creative giants. We swiftly gather that deep mistrust exists between the play’s Author and the Stage Manager, who is carrying out (so she glibly says) the wishes of the absent Director, who is in Leeds at a conference on Relevant Theatre, but is handily to be blamed for every alteration or indeed altercation.

Yet The Habit of Art is so onion-layered that it prompts you to question whose Auden this is that we’re seeing - Auden’s Auden, Britten's Auden? Bennett’s Auden, the biographers’ Auden? The set-up is that a new play, called "Caliban’s Day", is being rehearsed at the National Theatre itself about Britten and Auden’s reunion in 1972, and the unimpeachable Alex Jennings and Richard Griffiths play Henry and Fitz, actors cast as the two creative giants. We swiftly gather that deep mistrust exists between the play’s Author and the Stage Manager, who is carrying out (so she glibly says) the wishes of the absent Director, who is in Leeds at a conference on Relevant Theatre, but is handily to be blamed for every alteration or indeed altercation.

There is a further complication, in that within the fictional play the Author has introduced the figure of Humphrey Carpenter, the biographer of both Britten and Auden, and whose interpreter Donald (a perfectly pitched Adrian Scarborough) is the most hapless person on stage - trying to find his motivation (“My presence speaks! I am imagining you!”) but then realising, horrorstruck, “I’m only a device.”

This set-up is a masterstroke of creative procrastination, allowing for constant farcical double-takes. First we have the thoroughly enjoyable process of accustoming ourselves to Griffiths settling his vast bulk inside Bob Crowley's gross little set of a room in Christ Church, trying, without great conviction, to learn his lines and to play a grotesque with whom he has very little sympathy.

Foremost in his mind is that after this rehearsal he has a six o’clock voiceover to do for Tesco. He sarcastically enumerates his Auden props, including “my elephant urine-stained trousers, my disgusting handkerchief, my plastic bag. And have you got the mask?” This being a comical rubber Auden mask, as wrinkled as a scrotum, and no more seemly.

Fitz’s tolerance is increasingly tested by the toilet humour, a discussion about dicks that he has to have with a rent boy, and finally by an episode when Auden’s furniture starts declaiming poetry - at which Fitz quite reasonably snaps: “Do we need the talking furniture?” Oh, but we do, we do. The Talking Furniture is one of the choice display scenes for the dazzlingly funny Frances de la Tour as the Stage Manager, who is “reading” for Brian, one of the actors missing rehearsal as they are in “a Chekhov matinee”. This enables a great moment at the start of Act 2 where a man is just walking off the set (“Brian, you should go”), dressed in full Russian beard and serf costume.

The other masterfully taut spin-off of a first half that focuses so hard on the filthy Auden is that we get to know Jennings (pictured left) in his superbly prissy actorly persona, Henry, and hence have already made up our minds to dislike Britten when the fictional meeting does finally occur. Poor Britten. He’s almost a caricature (at first), the effete, sheltered narcissist, with his affectedness, snippy envy of others, and his bragging about his OM and his chauffeur.

The other masterfully taut spin-off of a first half that focuses so hard on the filthy Auden is that we get to know Jennings (pictured left) in his superbly prissy actorly persona, Henry, and hence have already made up our minds to dislike Britten when the fictional meeting does finally occur. Poor Britten. He’s almost a caricature (at first), the effete, sheltered narcissist, with his affectedness, snippy envy of others, and his bragging about his OM and his chauffeur.

And yet Bennett wholly changes the view during the meeting. Britten has come to tell Auden about his new opera Death in Venice. Auden thinks joyfully that Britten wants him to write the libretto. But no, selfish Britten only wants Auden to support his choice of a suggestive opera subject disliked by both his partner Peter Pears and his much inferior chosen librettist, Myfanwy Piper.

Delicately, Bennett suggests in this poignantly imagined scene that Britten, for all his self-absorption, felt much more raw, insistent pain about his condition than the blatant Auden ever could, and when Auden demands that Britten stop being “furtive” about the subject of an older man desiring a boy, the gap between words and music suddenly yawns, unbridgeable. Auden jokes that he rewrites his old poems, to stop himself being embarrassed. But Britten says, with music “I have to write it before I can write it.” This is a terrific conclusion, of penetrating seriousness in all the theatrical patisserie. It's a pity that the flavoursome confection is then thoroughly sunk at the end by pouring on a sticky luvvie hommage to the noble profession of acting, and the National Theatre in particular. But perhaps that's the Director talking, back from Leeds.

Add comment