Hans Werner Henze Day, Barbican | reviews, news & interviews

Hans Werner Henze Day, Barbican

Hans Werner Henze Day, Barbican

Political inanity and musical mastery from Germany's greatest living composer

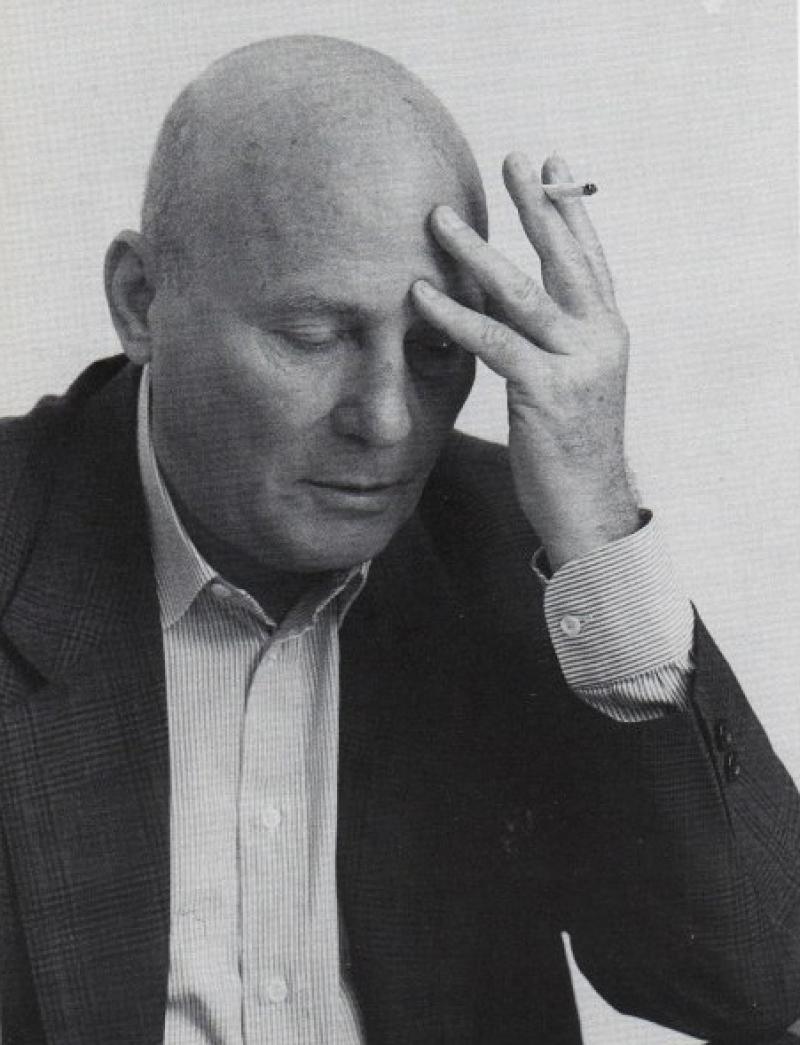

There was a brilliant moment in the film that began Henze Day yesterday. An ageing Henze, lazying on his Italian veranda, his leg cocked, his bald head - looking as if it had been iced - stuffed into a boater, is confronted by his lurcher dog, James. "Jamez," wheezes Henze, "Vat is it, honey? You vant to sit on my lap? Sis is impossible. Ve are at vork." It's an instructive little episode, a neat glimpse into the winning side of the German composer.

Voices, a 90-minute 22-part song-cycle written in 1973, was Henze's attempt to rectify the hypocritical conundrum that so many comfortably bourgeois but intellectually communist Western artists of that generation found themselves in: the all-talk-and-no-trousers conundrum. So here were Henze's trousers. Pungently confrontational, frustratingly one-dimensional, ennervatingly superficial flared numbers that might have looked good once but really should now be taken down to the musical equivalent of Oxfam.

One could hear the Henze stamp: the lyrical threads, mostly fractured and distributed among the musicians of the small ensemble, and a structural brilliance. But mostly, one was assaulted with crude populist musical images, denouncing American film and TV and wars. As a right-minded (and RIght-minded) sort of fellow, I decided to make a stand against this communist propaganda and walked.

There was a time when it was thought that Henze might save German music from the Nazi apocalypse. You hear Voices, you wonder how. Then you hear his Requiem (1990-1992) and it all becomes much clearer. The Requiem, perhaps better than any other work, shows the other side to Henze: the richly proficient side. In it we are acquainted with the Henzean sound-world at its finest.

So what exactly is this seductive Henzean world about? Well, a Henze piece might start with a bit of hide-and-seek tomfoolery. It will then give way to a lyrical passage: a harp haze with strings high up, divided into many parts, all undergirded by a solo rhythmical structure, usually simple, often repeated. The story from here is hardly ever formal, just intuitive. The initial harmonic, textural structure, however, recurs and recurs, perhaps most successfully in the fifth movement of the Requiem, the Rex Tremendae, a lively trumpet concerto, performed virtuosically by Hakan Hardenberger and the Ensemble Modern under the baton of Ingo Metzmacher.

Even more instructive, in this respect, was the evening concert. Here we could finally get a sense of the whole man, the whole compositional progression through the decades, with pieces ranging from his Opus 13 Variations for piano solo, written when he was only 22 in 1948, to one of the most recent orchestral works, the Elogium Musicum from 2008. (Antonio Pappano delivered a rendition of Henze's most recent orchestral work, Immolazione, in Rome last week.)

Henze's neo-romanticism, which got him into huge trouble with his former mates, the avant-garde gate-keepers, Boulez, Nono and Stockhausen, is evident from the start. Even in the heavily Webernised piano Variations (played by a supremely confidant Huw Watkins), there seems to be a romantic desire to tend to and revel in sound. Henze here loves to linger, hover, repeat and caress the notes. By the time of the Fourth Symphony (1955) and its very human beating heart, a sophisticated set of narrative musical tools has been added to the romantic longing. So, as in Fraternité (1999), there are several idyllic staging posts to stop and bathe in throughout this work, but never for too long. Oliver Knussen, conducting the BBC Symphony Orchestra, plumbed the pools of sensuousness while never letting the dramatic pace drop.

Most of the works in this evening programme were successful. Where they, now and again, let themselves down was in falling back on to too many four-square rhythms (as in Scorribanda Pianistica) or relapsing into his anger at Germany's murderous history. In Gavin Barrie's film, we see Henze explaining a musical passage by describing the burning of Berlin, the animals of Berlin zoo scattering into the fires, while he, Henze, patrolled the streets as a young conscript. One can't and shouldn't perhaps begrudge him this fixation. However, the deafening hollowness with which he seems to end almost every work on show (right from his early years to now), in which the orchestra or musician is suddenly struck down by a reign of indefinable but all-encompassing and insoluble terror (as if Henze is saying that nightmares are the only possible conclusions we can have any more), does make me sigh.

Having said that, Henze's work does, on the whole, stand up well to scrutiny. With almost every other Barbican composer day or weekend, boredom set in; the more one heard, the less one cared. Henze day alone left me more intrigued at the end than at the start. The more I listened, the better it got.

A new work, Elogium Musicum, dedicated to and written for his late partner of 50 years, Fausto Moroni, ended the evening on a note of almost unbearable rawness and intensity. At times, Henze's story-telling can careen into tragically naive political territory or be swallowed up too much by personal vortices, but it never ceases to engage. Tonight, we get a performance of Phaedra, a glimpse into the musical sphere Henze has become most famous for: opera. Not to be missed.

Phaedra is on tonight at the Barbican.

Add comment

more Classical music

Christian Pierre La Marca, Yaman Okur, St Martin-in-The-Fields review - engagingly subversive pairing falls short

A collaboration between a cellist and a breakdancer doesn't achieve lift off

Christian Pierre La Marca, Yaman Okur, St Martin-in-The-Fields review - engagingly subversive pairing falls short

A collaboration between a cellist and a breakdancer doesn't achieve lift off

Ridout, Włoszczowska, Crawford, Lai, Posner, Wigmore Hall review - electrifying teamwork

High-voltage Mozart and Schoenberg, blended Brahms, in a fascinating programme

Ridout, Włoszczowska, Crawford, Lai, Posner, Wigmore Hall review - electrifying teamwork

High-voltage Mozart and Schoenberg, blended Brahms, in a fascinating programme

Sabine Devieilhe, Mathieu Pordoy, Wigmore Hall review - enchantment in Mozart and Strauss

Leading French soprano shines beyond diva excess

Sabine Devieilhe, Mathieu Pordoy, Wigmore Hall review - enchantment in Mozart and Strauss

Leading French soprano shines beyond diva excess

Špaček, BBC Philharmonic, Bihlmaier, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - three flavours of Vienna

Close attention, careful balancing, flowing phrasing and clear contrast

Špaček, BBC Philharmonic, Bihlmaier, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - three flavours of Vienna

Close attention, careful balancing, flowing phrasing and clear contrast

Watts, BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, Bignamini, Barbican review - blazing French masterpieces

Poulenc’s Gloria and Berlioz’s 'Symphonie fantastique' on fire

Watts, BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, Bignamini, Barbican review - blazing French masterpieces

Poulenc’s Gloria and Berlioz’s 'Symphonie fantastique' on fire

Bell, Perahia, ASMF Chamber Ensemble, Wigmore Hall review - joy in teamwork

A great pianist re-emerges in Schumann, but Beamish and Mendelssohn take the palm

Bell, Perahia, ASMF Chamber Ensemble, Wigmore Hall review - joy in teamwork

A great pianist re-emerges in Schumann, but Beamish and Mendelssohn take the palm

First Persons: composers Colin Alexander and Héloïse Werner on fantasy in guided improvisation

On five new works allowing an element of freedom in the performance

First Persons: composers Colin Alexander and Héloïse Werner on fantasy in guided improvisation

On five new works allowing an element of freedom in the performance

First Person: Leeds Lieder Festival director and pianist Joseph Middleton on a beloved organisation back from the brink

Arts Council funding restored after the blow of 2023, new paths are being forged

First Person: Leeds Lieder Festival director and pianist Joseph Middleton on a beloved organisation back from the brink

Arts Council funding restored after the blow of 2023, new paths are being forged

Classical CDs: Nymphs, magots and buckgoats

Epic symphonies, popular music from 17th century London and an engrossing tribute to a great Spanish pianist

Classical CDs: Nymphs, magots and buckgoats

Epic symphonies, popular music from 17th century London and an engrossing tribute to a great Spanish pianist

Sheku Kanneh-Mason, Philharmonia Chorus, RPO, Petrenko, RFH review - poetic cello, blazing chorus

Atmospheric Elgar and Weinberg, but Rachmaninov's 'The Bells' takes the palm

Sheku Kanneh-Mason, Philharmonia Chorus, RPO, Petrenko, RFH review - poetic cello, blazing chorus

Atmospheric Elgar and Weinberg, but Rachmaninov's 'The Bells' takes the palm

Daphnis et Chloé, Tenebrae, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - lighting up Ravel’s ‘choreographic symphony’

All details outstanding in the lavish canvas of a giant masterpiece

Daphnis et Chloé, Tenebrae, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - lighting up Ravel’s ‘choreographic symphony’

All details outstanding in the lavish canvas of a giant masterpiece

Goldscheider, Spence, Britten Sinfonia, Milton Court review - heroic evening songs and a jolly horn ramble

Direct, cheerful new concerto by Huw Watkins, but the programme didn’t quite cohere

Goldscheider, Spence, Britten Sinfonia, Milton Court review - heroic evening songs and a jolly horn ramble

Direct, cheerful new concerto by Huw Watkins, but the programme didn’t quite cohere

Comments

...