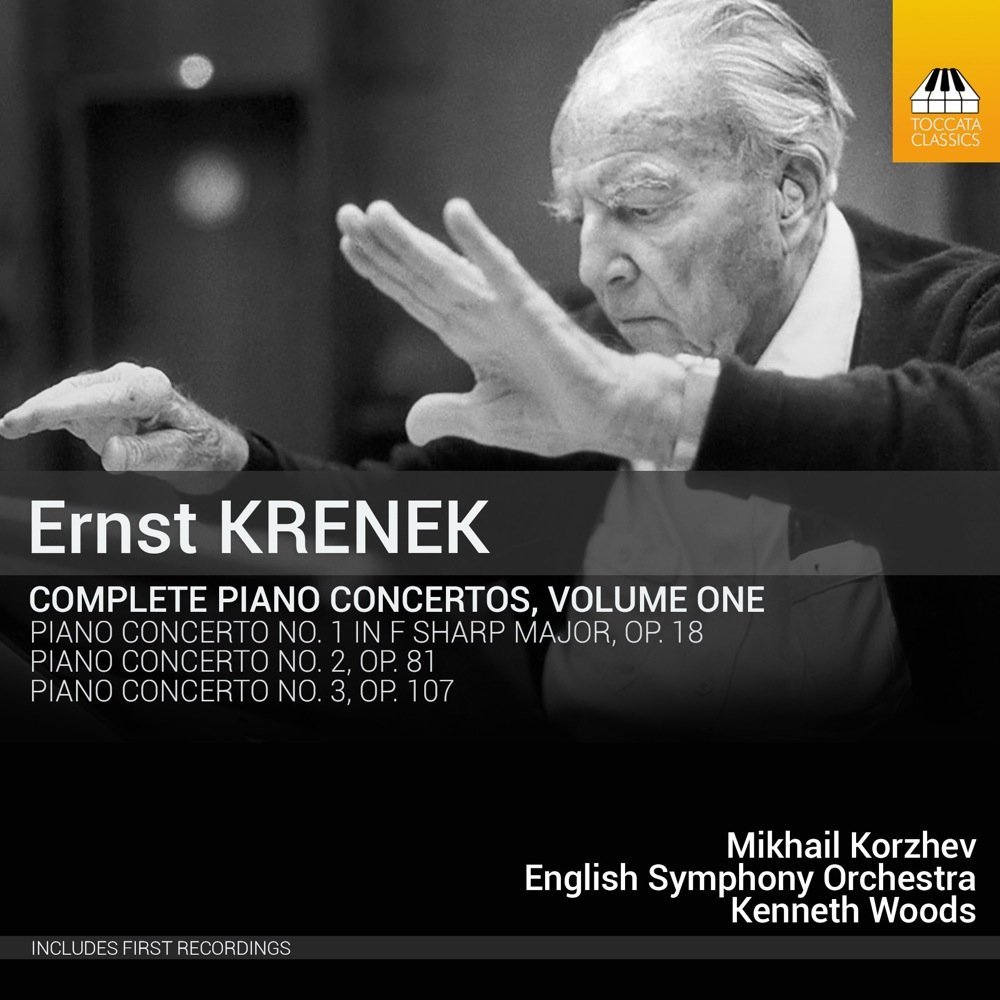

Krenek: Piano Concertos 1-3 Mikhail Korzhev (piano), English Symphony Orchestra/Kenneth Woods (Toccata Classics)

Krenek: Piano Concertos 1-3 Mikhail Korzhev (piano), English Symphony Orchestra/Kenneth Woods (Toccata Classics)

Ernst Krenek? If he's remembered at all, it's for his jazzy Weimar Republic opera Johnny spielt auf. This was an international hit after its 1927 premiere, though swiftly banned when the Nazis came to power. Krenek rubbed shoulders with many 20th century greats, before fleeing to the US in 1938; he remained there, teaching and composing until his death in 1991. He's an important figure, so this disc deserves a warm welcome. Krenek wrote four piano concertos and here are Nos. 1-3, written between 1923 and 1946. No. 1 is tonal though highly chromatic. Orchestrated with dazzlingly clarity, it's a real find, the brief slow movement wonderfully eerie. The concerto's close is quietly brilliant, the minuet fizzling out into calm silence. The Concerto No. 2 is completely different: five dark movements written in a highly approachable 12-note idiom, the angst and nostalgia reflecting Krenek's respect for Berg's music. Again, there's a wonderful ending, the disconcerting but deeply satisfying fade to black entirely appropriate for a work written in 1937.

Both are superb appetisers for Krenek's startlingly brilliant Third Concerto, its 13 minutes smarter than many 50-minute symphonies. Five short movements have the soloist sparring with different orchestral sections, before a rousing atonal fugue closes proceedings – like a grumpier, dodecaphonic version of Britten's Young Person's Guide. At one point the soloist duets with the orchestral harpist by reaching inside the lid and strumming the piano strings. Mikhail Korzhev is a heroic soloist, gamely accompanied by Kenneth Wood's English Symphony Orchestra. Brass and percussion are particularly impressive. And what good sleeve notes: three essays, by music historian, conductor and pianist respectively. Each one a joy to read and full of insight, outlining with erudition and passionate enthusiasm exactly why these pieces demand to be heard. More please.

Schumann: Violin Concerto, Symphony No. 1, Phantasy for Violin and Orchestra Thomas Zehetmair (violin and conductor), Orchestre de chambre de Paris (ECM)

Schumann: Violin Concerto, Symphony No. 1, Phantasy for Violin and Orchestra Thomas Zehetmair (violin and conductor), Orchestre de chambre de Paris (ECM)

Schumann's valedictory Violin Concerto still hasn't found a place in the repertoire. ECM's sleeve notes understandably bemoan the fact that “the bizarre circumstances of its rediscovery and première have become better known than the work itself.” Without mentioning said bizarre but fascinating circumstances, namely that the unpublished concerto was rediscovered after Schumann's supposed appearance during a 1933 séance, followed by an unseemly scramble between various parties interested in securing the first performance. The whole affair would make for a terrific film. Thomas Zehetmair has sung the work's praises since first recording it in the late 1980s, refusing to tamper with Schumann's violin line. This new version was recorded in 2014, and the virtues haven't changed. Zehetmair directs as well as taking the solo role, and his is flawless, confident playing, the solo writing always sounding idiomatic. But the piece is frustratingly unbalanced; a brooding, expansive first movement and a melting Langsam precede a rambling, insubstantial Polonaise finale which feels three times too long for its material. You can't imagine a better case being made for the piece, but it's not one I'll return to often. More musically coherent is Schumann's innovative single movement Phantasy for Violin and Orchestra, the technical and musical demands smartly handled by Zehetmair.

Schumann's breezy Symphony No. 1 is this disc's light relief. You don't associate French orchestras with this music, but Zehetmair's Parisians provide an invigorating listening experience. Perky woodwinds and impeccable string articulation make this reading a joy, especially in a propulsive last movement. The big snag is the recording quality: ECM’s sound feels much too close and dry, the sonorities lacking warmth and bloom.

Osmosis:Tafahum (Tafahum Records)

Osmosis:Tafahum (Tafahum Records)

Iffy sleeve art and the promise of “a new, vibrant and first class fusion group” made me fear the worst, but this disc surpassed my expectations within the first few seconds. A harmonious collaboration between the young British composer and conductor Benjamin Ellin and the Syrian multi-instramentalist Louai Alhenawi, Tafahum (an Arabic word for ‘understanding’) works beautifully. The music they've composed together is miles away from the bland bilge which can pass for classical crossover. There's no indication given as to how the pair created the album, but the eight pieces assembled are beguilingly scored and intelligently structured. The introspective numbers are the highlights: the shifting string chords which accompany flickering ostinati figures played on the saz and qanun (two Arabic stringed instruments) at the start of “Three Fishes Laughing” are magical, but Ellin and Alhenawi are too wise too endlessly repeat the trick; the music constantly evolves, Alhenawi's languid Arabic flute solo at the piece's centre never sounding out of place.

“LouLou” has a similarly effective calm opening, and there's a beautiful slow horn solo at the start of “Sketching Jeffrey”. The faster movements recall music by several contemporary minimalists: the tuned percussion in “Crossing Green” owing a clear debt to Steve Reich. All good, in other words, and very well recorded – the busy textures never sound congested.

Add comment