Back in the early Sixties Lucian Freud was living in Clarendon Crescent, a condemned row of houses in Paddington which were gradually being demolished around him. The neighbourhood was uncompromisingly working class and to his glee his neighbours included characters from the seamier side of the criminal world. It was around the time of his fortieth birthday when the wrecking balls drew near and, Bentley-owning but broke and generally neglected by the art world, his work began to develop into what is now known as late Freud. In relative obscurity eking out extravagance from precarity and painting and gambling until the early hours, Freud set himself back on the path to becoming the artistic megalith he remains today.

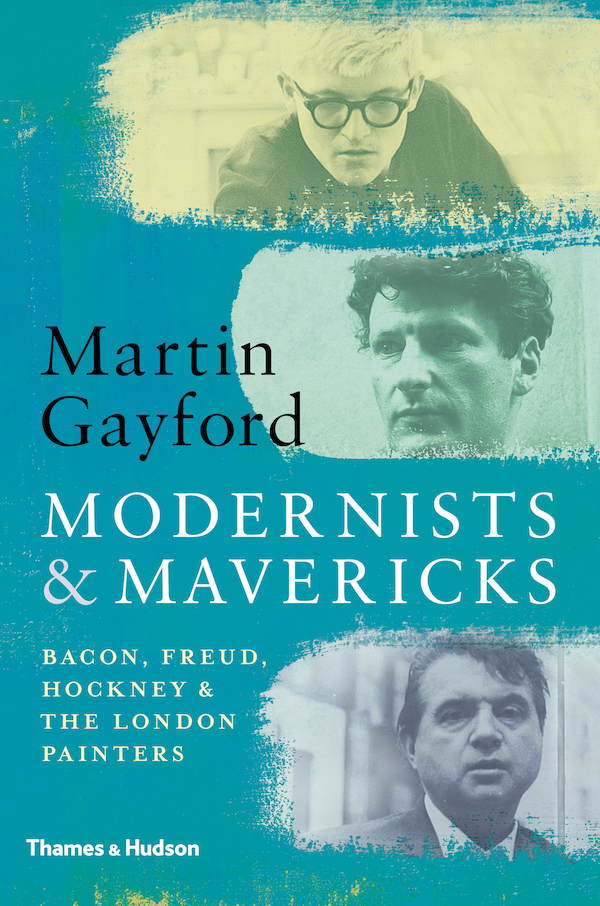

This recollection (via Frank Auerbach) of bloodyminded auto-didacticism is a recurring of theme in Martin Gayford’s new book, Modernists & Mavericks — which is as much a meditation on the fickleness of fame and favour as it is a survey of the painters working in London during the quarter century between 1945 and 1970. It is also a portrait of the city as it mutated out of the debris of war and formed something akin to the shape that can still be loosely discerned in its current lineaments. What characterises the massively divergent artistic approaches the loose grouping of London painters pursued during the post-war years was, according to Gayford, a kind of renegade flair and awareness of the fact of the city, whether found in its industrial accoutrements, social loci or simply in a particular kind of light.

This recollection (via Frank Auerbach) of bloodyminded auto-didacticism is a recurring of theme in Martin Gayford’s new book, Modernists & Mavericks — which is as much a meditation on the fickleness of fame and favour as it is a survey of the painters working in London during the quarter century between 1945 and 1970. It is also a portrait of the city as it mutated out of the debris of war and formed something akin to the shape that can still be loosely discerned in its current lineaments. What characterises the massively divergent artistic approaches the loose grouping of London painters pursued during the post-war years was, according to Gayford, a kind of renegade flair and awareness of the fact of the city, whether found in its industrial accoutrements, social loci or simply in a particular kind of light.

Time and again Gayford draws attention to the way specific places fatefully informed artists’ work: the Willesden Green public pool leading to Leon Kossoff’s exuberant, miasmic, ovidian pool paintings (one is currently on display at the Tate Britain’s excellent if expensive All Too Human exhibition), the canals of Peckham which were the setting for a conversation between William Coldstream, Victor Passmore and William Townsend into the distinction between painters interested in the world outside of themselves and those painting from the inside, and Prunella Clough’s excursions to depict the industrial fringes of the city in Woolwich, Canning Town and Acton East.

He also takes us inside painters’ houses and studios. Aside from intriguing contrasts drawn between the hectic unruly disorder of Bacon’s studio and the furiously mathematical contraptions to which Euan Uglow subjected himself and his models, two charming photographs stand out: an aquiline Freud in striped jumper caressing a stuffed zebra head, and Frank Bowling leaning on a fire mantel above which geometric diagrams painted direct onto the wall lay out with Euclidian severity his theories of art.

Gayford’s material is drawn largely from conversations with many of the artists involved over the years, not least Gillian Ayres who died earlier this April, and this lends the book an intimate tone as it traces the gestation of new ways of seeing, looking and painting through time and through the artists who conceived them. Innovation and new means of painterly expression therefore take of a convivial air and the book is a joyful, human read for it.

Gayford’s material is drawn largely from conversations with many of the artists involved over the years, not least Gillian Ayres who died earlier this April, and this lends the book an intimate tone as it traces the gestation of new ways of seeing, looking and painting through time and through the artists who conceived them. Innovation and new means of painterly expression therefore take of a convivial air and the book is a joyful, human read for it.

This approach brings forth without affectation the deep impact significant personal events could have upon individual painters without succumbing to a tedious kind of biography. So the role that Soho played in the personal and painterly lives of Bacon, Freud, Robert Colquhoun, Robert MacBryde and John Craxton figures early, and the tectonic movements that shifted the locus of artistic excitement from Europe to America and that put British artists in contact with contemporaries across the Atlantic are therefore told through the gravitations of David Hockney and Richard Smith towards Los Angeles and New York. It also allows the book to do something that galleries often don’t, can’t, or omit to do — namely allow the history of friendships and competitions to soften overly sharp distinctions between schools of artistic thought. It is fair to say that during those twenty five years the Euston Road, Camden Town, and Borough groups set young artists off along distinct paths, but as many chafed under their tutors as were inspired by them and what is distinctive is how many ended up forging their own ways and how influences and friendships cut across styles and approaches.

It also allows the book to do something that galleries often don’t, can’t, or omit to do — namely allow the history of friendships and competitions to soften overly sharp distinctions between schools of artistic thought. It is fair to say that during those twenty five years the Euston Road, Camden Town, and Borough groups set young artists off along distinct paths, but as many chafed under their tutors as were inspired by them and what is distinctive is how many ended up forging their own ways and how influences and friendships cut across styles and approaches.

A great deal has changed since 1945 and even the London of the 1970s feels far off. Some of the artists in Gayford’s book are still practising and exhibiting — notably Bridget Riley and David Hockney. But they are living icons and the artistic establishment surrounding these artists who were once young and unknown is now setting the public agenda. While they rightfully take their place in the gallery of greats, what Gayford’s book eloquently traces is that while new art incubated in London might be informed by work that came immediately before, the direction of the new artists’ reaction will never be predictable.

- Modernists & Mavericks by Martin Gayford (Thames & Hudson, £24.95 hardback)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment