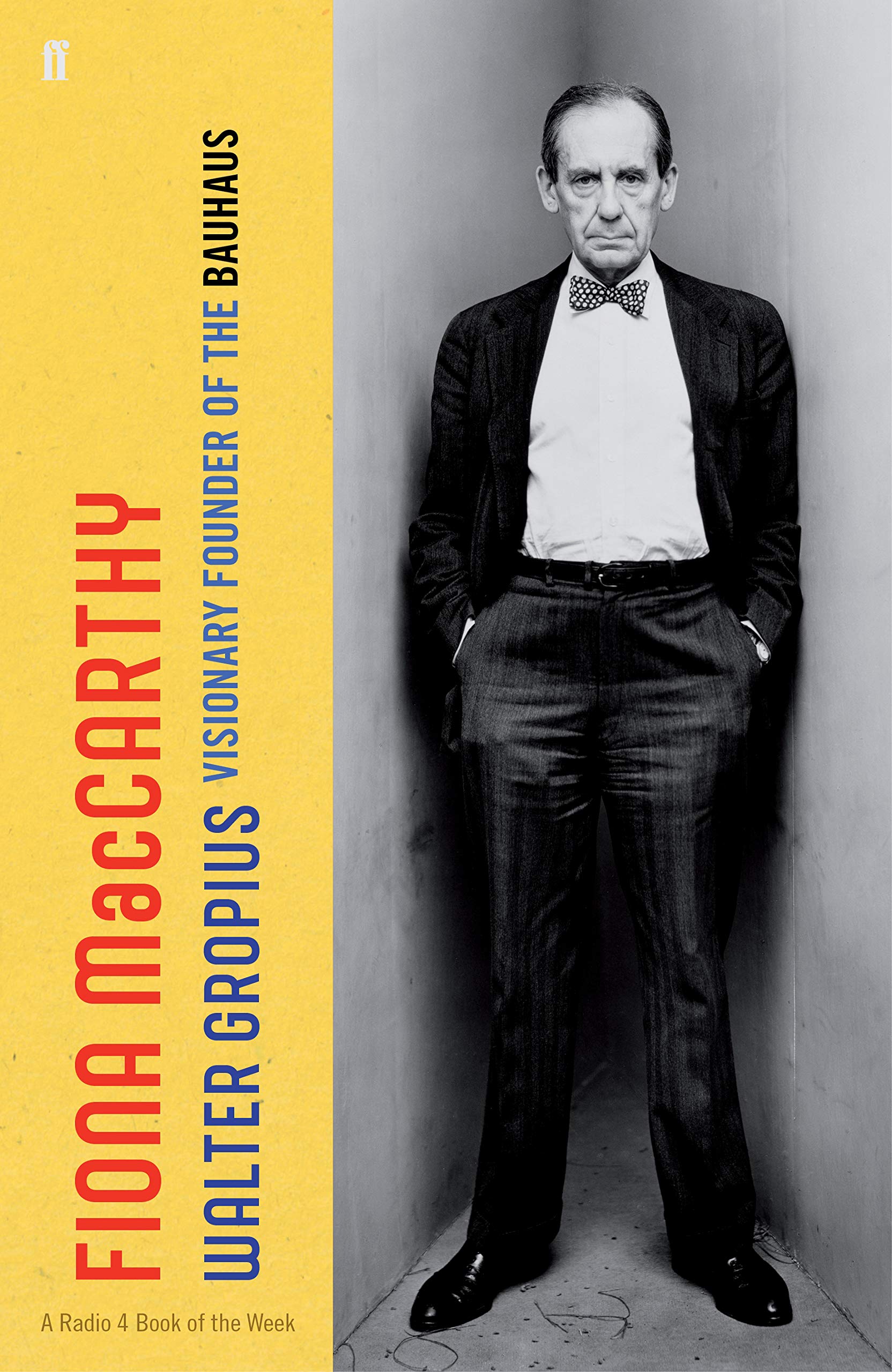

The centenary of the founding of the Bauhaus (literally, “Building House”) art school is on us, prompting publications and exhibitions worldwide. Subtitled “Visionary Founder of the Bauhaus”, Fiona MacCarthy’s revelatory biography of the figure instrumental in establishing it, the upper-middle-class Walter Gropius (1883-1969), will be a major contribution, strikingly readable and elegantly designed as it is. Based on five years of exhaustive research, her book expands our understanding of Gropius as well as the cultural history of the 20th century.

For nine years Walter Gropius was the first Bauhaus director before, exhausted and wanting to concentrate on his own work as an architect, he handed over, unsatisfactorily, to the communist Hannes Meyer; when Meyer eventually went to Moscow, he was succeeded by Mies van der Rohe. A hundred years on, the ideals, ideas and teaching of the short-lived Bauhaus – it lasted only until 1933, moving from Weimar to Dessau and finally to Berlin until the toxic atmosphere of Nazi Germany shut it down – have disseminated throughout the world, for good and sometimes times for ill (especially when misinterpreted).

MacCarthy is the accomplished biographer of the English Arts and Crafts movement, of William Morris and Eric Gill among others – Morris was an ideal for Gropius – and genuinely changes the conventional endemic view not only of the Bauhaus but of Gropius. The popular perception, fuelled by Tom Wolfe’s 1981 polemic From Bauhaus to Our House is of practitioners, led by Gropius, who promulgated an uptight, rigid, doctrinaire architecture responsible for the endlessly bland and blank corporate glassy skyscrapers which now dominate cities worldwide.

MacCarthy is the accomplished biographer of the English Arts and Crafts movement, of William Morris and Eric Gill among others – Morris was an ideal for Gropius – and genuinely changes the conventional endemic view not only of the Bauhaus but of Gropius. The popular perception, fuelled by Tom Wolfe’s 1981 polemic From Bauhaus to Our House is of practitioners, led by Gropius, who promulgated an uptight, rigid, doctrinaire architecture responsible for the endlessly bland and blank corporate glassy skyscrapers which now dominate cities worldwide.

As MacCarthy makes clear, the manifesto of the Bauhaus was very different. The various groups – also famed for their wild, imaginative parties and general carryings-on – were committed to a reinterpretation of medieval crafts and to working in harmony. To that end there were not teachers and pupils but masters, journeymen and apprentices. Sculpture, painting, the applied arts and handicrafts were to be permanent elements of a new architecture which took into account its inhabitants, context and natural environment. Whatever technology could offer was also to be embraced.

“Building House” was a bland name for the synergy between a group of energetic, imaginative, skilled and hopeful pioneers seeking what they could achieve for a brave new world – no irony intended – after the cataclysm of World War One. After all the horrors, these clever, hardworking thirtysomethings searched for ways both conceptual and visible to make the world a better place. Filling in that context in reverse, as it were, MacCarthy gives us the appalling details of Gropius’ war service: he was wounded several times, buried alive for three days in an explosion, and survived with memories of the dead and dying. He was certainly haunted by what is now termed PTSD.

MacCarthy is an unabashed fan: she not only respects her subject, she clearly likes him, too

Gropius emerges here as a kind of obsessive, passionate genius. He was evidently also enormously attractive, which again belies popular perception. He had an affair with Alma Mahler, the over-the-top Viennese femme fatale, when she was married to the composer, and became her second husband, although she more or less wrote him out of her personal history in her self-serving autobiography, and kept him from engaging with their daughter Mutzi, who died aged only 18 from complications from polio. He had passionate affairs with talented younger women – among them the married painter, free-spirited Lily Hildebrandt, and the widow and poet Maria Benemann – whilst not yet divorced from Alma, although their marriage was over. He finally married Ise Frank, whose administrative skills saw her nicknamed “Mrs Bauhaus”; they had a long-lived profound attachment, but even that was disturbed by Ise’s affair with the designer Herbert Bayer. All too human and fascinating: they must all have had a genius for time management, among other things. The wider crowd dazzles, a company that included Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Josef Albers (who transformed art education in the US) and his wife Anni, Marcel Breuer, Bayer and van der Rohe.

MacCarthy details the opposition to Bauhaus ideals and practices in the conservative cities in which they had their peripatetic being. The delicate matter of how, for example, Gropius – he did not get to London until the mid-1930s – managed in the increasingly hostile and difficult climate of Germany, despite his devotion to his homeland, seemed to be a combination of keeping his head below the parapet while also doing the best he could for those who were more actively persecuted than he was. But in that horribly unpleasant middle-class way he was capable of casual anti-Semitic remarks, and this is perhaps the most difficult part of the narrative: but MacCarthy poses that dreadful question to the reader, too – what would you have done?

When he got to England, he and Ise were welcomed very warmly by the country’s comparatively small modernist crowd. Jack and Molly Pritchard were instrumental in providing accommodation in the Lawn Road Flats (the Isokon Building) designed by Wells Coates, still a marvel of modernism. But there was little work, and at that point Gropius’ English was poor. Finally, with the offer of a teaching post at Harvard, Ise and Walter crossed the Atlantic, to settle in Massachusetts for the rest of their lives. He designed their own home there, in Lincoln, as well as the building that MacCarthy considers his masterpiece, the PanAm skyscraper above Grand Central Station in New York.

What is left elsewhere from Gropius? Still surviving is the Fagus Factory with its pioneering glass walls, the Bauhaus building in Dessau, and studios and domestic housing for the Bauhaus Masters, recently restored. In Britain there is the acclaimed Village College in Impington, near Cambridge, and a modernist residence in Old Church Street, Chelsea. It would have been helpful to have as an appendix a list of all the buildings, surviving or not, with which Gropius was involved, although they are detailed in MacCarthy’s narrative. Sometimes, though, the details become almost too much as over the last three decades of his life Gropius whirls round the world, receiving honoured, giving lectures and working on architectural projects.

Walter Gropius: Visionary Founder of the Bauhaus transforms our understanding of the history and significance not only of Gropius but of the group of 1930s innovators who comprised the movement. MacCarthy is an unabashed fan: she not only respects her subject, she clearly likes him, too. In the law of unintended consequences, scores of Bauhaus teachers and students became Hitler’s gift to a wider Europe, North America and beyond. Forced out of the German-speaking world, their inventions of new ways of thinking, looking, designing and building for modern times are today visible all around the world. It is MacCarthy’s gift to show us how this happened.

- Walter Gropius: Visionary Founder of the Bauhaus by Fiona MacCarthy (Faber £30, e-book £19.99)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment