Ed Vulliamy: When Words Fail review - the band plays on | reviews, news & interviews

Ed Vulliamy: When Words Fail review - the band plays on

Ed Vulliamy: When Words Fail review - the band plays on

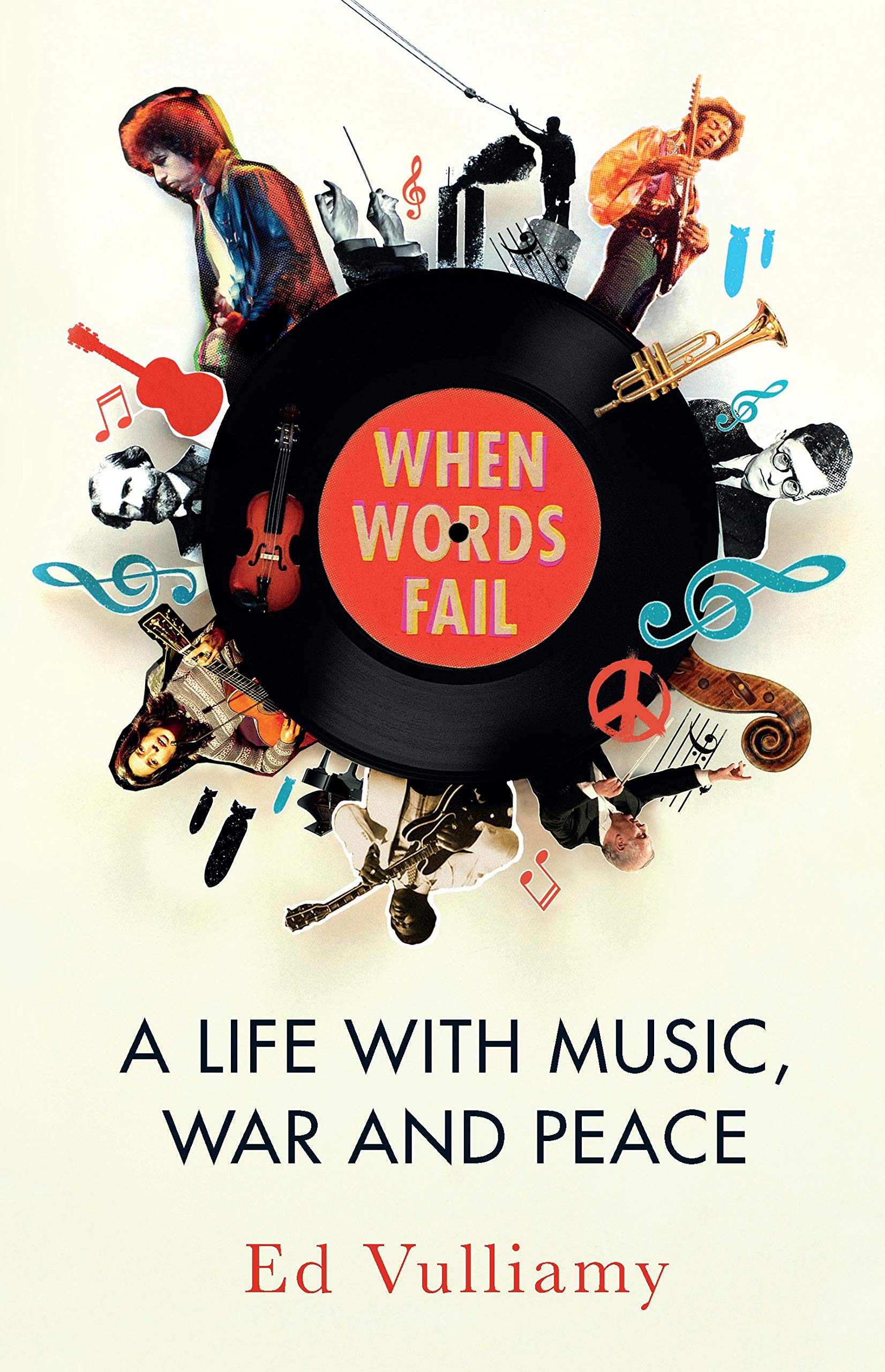

Autobiography interwoven with a polyphony on music's healing in war and peace

If you're seeking ideas for new playlists and diverse suggestions for reading - and when better to look than at this time of year? - then beware: you may be overwhelmed by the infectious enthusiasms of Ed Vulliamy, hyper-journalist, witness-bearer, true Mensch and member of the first band to spit in public (as far as he can tell).

Yet it would be wrong to suggest that this is a book where passions swirl in some half-connected vortex. Vulliamy's writerly discipline weaves a marvellous tapestry: in essence an autobiography, more or less chronological, and dealing, as the title suggests, with the power of music in times and places of the greatest trouble, but without the egotism usually attendant on the big "I". Because he's interviewed so many fascinating people all over the world, and been to so many of its war zones, the multiple meanings of what happens "when words fail" achieve a rich polyphony, a handbook of musical wisdoms which merely embrace the author's own.

His eloquent prose is as good at assessing his own motivations as those of others. “There’s a journalistic imperative and a need to bear witness ingrained in my nature…It’s some urge that dictates: if possible, be there, see it, put faces to the news, humanize the historic moment, preferably with a soundtrack". He admits that he’s also "unable to separate journalistic privilege from curiosity-killed-the-cat…determined to join the dots, fogure out what is really happening, explore what Italians call dietrologia, the science of what lies behind things". Which he does, for weeks, months, after the assignment, funding his curiosity out of his own pocket. While always conscious of the bigger picture, he is equally strong on self-analysis, disarming about the form of PTSD which overtook him recently; you get inside the terror and strangeness of it.

His eloquent prose is as good at assessing his own motivations as those of others. “There’s a journalistic imperative and a need to bear witness ingrained in my nature…It’s some urge that dictates: if possible, be there, see it, put faces to the news, humanize the historic moment, preferably with a soundtrack". He admits that he’s also "unable to separate journalistic privilege from curiosity-killed-the-cat…determined to join the dots, fogure out what is really happening, explore what Italians call dietrologia, the science of what lies behind things". Which he does, for weeks, months, after the assignment, funding his curiosity out of his own pocket. While always conscious of the bigger picture, he is equally strong on self-analysis, disarming about the form of PTSD which overtook him recently; you get inside the terror and strangeness of it.

Anyone who covers so much musical terrain is bound to be challenged by experts with a narrower frame of reference. It’s not my intention to nitpick over some factual errors in the Russian field, though a big general misconception is oneVulliamy shares honourably enough with composer as well as novelist Anthony Burgess: you cannot “rise to a crescendo” unless that in itself begins another rising. Opinion-wise, I don’t know anyone else who would place Shostakovich's potboiler operetta Moscow Cheryomushki, cobbled together from various sources, as a gem in the tradition of Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro,nor find it “charged with some of the composer’s most profound and enigmatic statements about any society”. The spotlight on Valery Gergiev, a conductor I once admired hugely, too, maybe needs some qualifying in the light of recent events (we both attended a protest organised by Peter Tatchell outside the Barbican). But I'm eternally grateful to Vulliamy for much discovery on YouTube and elsewhere, even if I made the mistake of buying a Joan Baez album where it turns out "Diamonds and Rust" is the only really good song.

Yet this is a book too treasurable for any niggling reservations. Any of its many seams is rich with vital quotations. The ones I’ve earmarked come from Balkan singer Amira, on music opposing tribalism; violinist Nabeel Abboud Ashkar of Nazareth’s Polyphony Foundation, on the necessary discipline of western classical orchestral and chamber music in the Middle East; John Cale on musical memory as immune to political manipulation; and pianist Paul Lewis on his teacher Alfred Brendel’s insistence on getting the message of the music across. As most of these preoccupations are eternal, there is one observation which stands out right now with a different resonance to the one it had for Nigel Osborne in Sarajevo: “When established politics is dead and trivial, and politicians are demonstrably part of the problem and not the solution, culture becomes the only democratizing agent". For that reason, as well as the sheer vivacity of Vulliamy’s prose, this is the best possible book to accompany you into the worrying maelstrom of 2019.

- When Words Fail: A Life With Music, War and Peace by Ed Vulliamy (Granta, £25)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment