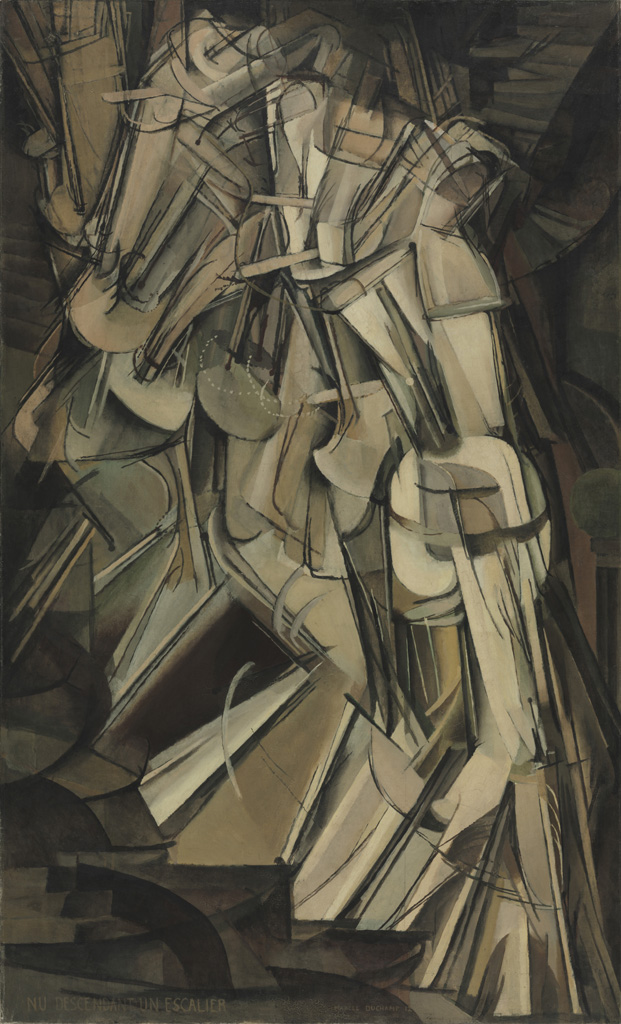

Walk up Central Park West, past the Dakota building and all those plush-looking podiatrists’ offices with their gold plaques, and just before you get to the Museum of Natural History you’ll find the New-York Historical Society and Museum at 77th Street (it also houses a great research library, open to all). Descending its steps is a life-size replica of Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (pictured below), and on the day I visited some school kids were yelling, "That’s a nude woman? What? Where? I don’t see it."

Very similar to the reaction that many artists, critics and visitors had to Duchamp’s nude at the 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art, a huge, controversial show held at the 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue, which the New-York Historical Society is celebrating in this centennial (the catalogue is also huge, and beautifully produced). The 1913 Armory gave Americans their first massive, shocking hit of abstract art and it’s the historical context that makes this exhibition so fascinating – and why the N-YHS is the right place for it.

The 1913 show was put on 16 years before the opening of the Museum of Modern Art, before colour repro and six-hour hops across the pond. The likes of Picasso, Matisse, Gauguin, Munch, Redon, Kandinsky and Braque were astonishingly new and often incomprehensible (works by Delacroix, Renoir, Cezanne, Manet and Degas, also thought insane in their day, were included to give a historical thread). The show’s emblem, a pine tree, was taken from the flag flown during the Revolution and it was billed as an embodiment of the New Spirit. Some people were repelled, some ridiculed this childish rubbish. Others were hysterically excited: "the most important event since the signing of the Declaration of Independence," wrote art patron Mabel Dodge to Gertrude Stein, who lent two Picassos and a Matisse.

The 1913 show was put on 16 years before the opening of the Museum of Modern Art, before colour repro and six-hour hops across the pond. The likes of Picasso, Matisse, Gauguin, Munch, Redon, Kandinsky and Braque were astonishingly new and often incomprehensible (works by Delacroix, Renoir, Cezanne, Manet and Degas, also thought insane in their day, were included to give a historical thread). The show’s emblem, a pine tree, was taken from the flag flown during the Revolution and it was billed as an embodiment of the New Spirit. Some people were repelled, some ridiculed this childish rubbish. Others were hysterically excited: "the most important event since the signing of the Declaration of Independence," wrote art patron Mabel Dodge to Gertrude Stein, who lent two Picassos and a Matisse.

Brancusi’s sculpture of Mlle Pogany was compared to an egg on a sugar cube; Matisse, who had 13 paintings, including the Red Studio and Blue Nude, three drawings and a sculpture in the show, was seen as "poisonous" and backward-looking (so un-American) because rooted in childhood. When the show moved on to Chicago, some art students burned copies of three of his paintings and called him Henri Hair-Mattress. Duchamp’s nude unleashed a stream of ridicule ("an explosion in a shingle factory") as well as an intriguing children’s alphabet book, the Cubies, where he was called the Deep-Dyed Deceiver.

Where was the shared visual language that was supposed to exist between artist and viewer in this new, confusing world? Was Cubism just "charlatanry" or was it part of a logical development in art? All this controversy was good for business. Eighty-seven thousand people saw the show in New York during the month that it was on; in Chicago, more than double that number. A clever San Francisco art dealer bought the Duchamp nude for $324 and sold it six years later to collector Walter Arensberg for $1000. Altogether, about $45,000 worth of art was sold.

The Armory at 100 has a fraction of what was on show in 1913: 90 works as opposed to 1,400. Perhaps most intriguing is the American art. Half the works in the 1913 show were by Americans, many of them more or less forgotten now. Who’s ever heard of Robert Chanler, an artist who specialized in painted screens, mostly with animal motifs? His gorgeous Leopard and Deer is the only screen of his on show in the N-YHS (there were 11 in 1913), though his bizarre painting, Parody of the Fauve Painters, representing Matisse as an ape surrounded by fey acolytes hanging on his utterances is also here. Or Walter Pach and Walt Kuhn, artists and organizers of the exhibition and influential figures in their day?

Most of the American artists, with their provincial, antiquated realism, were scorned for lack of innovation – and were relegated to the outer edges of the 18 galleries in the 1913 show. At the N-YHS, some balance is restored. John Sloan’s Sunday, Women Drying their Hair on a tenement roof, Alfred Maurer’s Autumn, Albert Pinkham Ryder’s Moonlit Cove are stand-outs. The Armory was a disaster for American art, said painter Fairfield Porter 50 years after the show – but in the words of Leo Stein it "created a new epoch", unleashing a market for the avant-garde. Many new galleries opened in New York afterwards.

Most of the American artists, with their provincial, antiquated realism, were scorned for lack of innovation – and were relegated to the outer edges of the 18 galleries in the 1913 show. At the N-YHS, some balance is restored. John Sloan’s Sunday, Women Drying their Hair on a tenement roof, Alfred Maurer’s Autumn, Albert Pinkham Ryder’s Moonlit Cove are stand-outs. The Armory was a disaster for American art, said painter Fairfield Porter 50 years after the show – but in the words of Leo Stein it "created a new epoch", unleashing a market for the avant-garde. Many new galleries opened in New York afterwards.

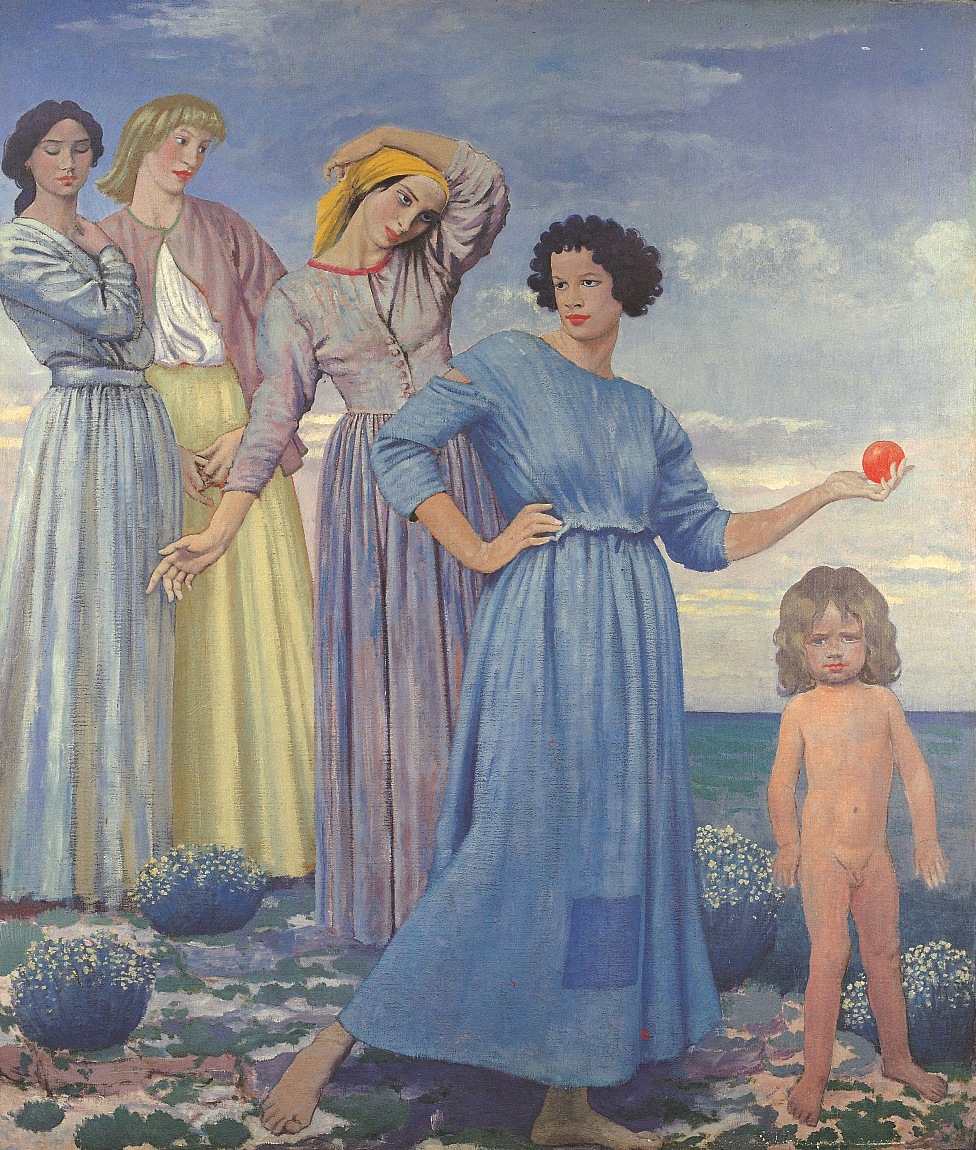

It was the mysterious symbolism of Odilon Redon that was the biggest hit with the public (Puvis de Chavannes was also seen as a good antidote to the scourge of abstraction; Teddy Roosevelt was a fan). The organisers included 76 of Redon’s works and he sold more than any other artist (13 paintings and 20 prints). Augustus John ("no longer well known" says the wall label, rather unfairly) was also heavily represented – 38 paintings and drawings – and was well received. In the N-YHS’s show there’s only one by him, the monumental Way Down to the Sea (pictured above left) which, with its four women and naked child, may well look as strange today as it did in 1913.

Credits:

Augustus John: The Way Down to the Sea, 1909–11 (Private collection. Photo, Richard Greenly Photography)

Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, 1912 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, © 2013 Artists Rights Society)

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment