At last, after waiting several years, we get to see Philip Guston’s paintings at Tate Modern. His retrospective was scheduled to open in summer 2020 at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, but the murder of George Floyd made the institution nervous. The problem? Guston’s absurdist paintings of Klu Klux Klan (KKK) members. They could be seen to condone white supremacy or, at least, to make light of it. So the show was postponed until the artist’s intentions could be made clear.

Hannah Arendt’s phrase “the banality of evil” sums up the ethos of these cartoon-like pictures. Made in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Guston used black comedy to underscore what he described as “the brutality of the world”. Evil hides in plain sight; hooded KKK members cruise the streets in clapped out Model T Fords and sit smoking in ordinary living rooms; they even take up painting self-portraits. Most chilling and most horribly prescient of all is their appearance on a blackboard, warning of the infiltration of racist doctrines into American class rooms.

I don’t know how much detail about Guston’s background and political orientation has been added for clarification, but the information is fascinating and it illuminates his work. Born in 1913 to Jewish parents who fled to the United States from persecution in Ukraine, Guston was acutely aware both of antisemitism and racism in general. “The KKK has haunted me since I was a boy in Los Angeles”, he said. And since, in the 1920s, the Chief of Police and the President of the City Council were members of this vile organisation along with several million others, his obsession was understandable.

I don’t know how much detail about Guston’s background and political orientation has been added for clarification, but the information is fascinating and it illuminates his work. Born in 1913 to Jewish parents who fled to the United States from persecution in Ukraine, Guston was acutely aware both of antisemitism and racism in general. “The KKK has haunted me since I was a boy in Los Angeles”, he said. And since, in the 1920s, the Chief of Police and the President of the City Council were members of this vile organisation along with several million others, his obsession was understandable.

Wanting to respond through painting, he looked for guidance on how to depict violence in the work of Renaissance masters like Piero della Francesca. He joined the Bloc of Painters, a group run by Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros. Dedicated to producing public art projects that promoted workers’ rights and racial equality in the U.S, they were funded by President Roosevelt’s New Deal. In 1934 he was commissioned with Reuben Kadish and Jules Langsner to paint a huge fresco in Morelia, Mexico. Projected large onto the gallery wall, a video of The Struggle Against Terrorism shows Klansmen portrayed as torturers alongside the hooded priests of the Spanish Inquisition.

Not long after, Guston turned his attention to easel painting. In response to the bombing of the town of Guernica which inspired Picasso’s eponymous work, for instance, he painted Bombardment 1937 (pictured above right). Shaped like a Renaissance tondo, it shows victims being hurled outwards by the centrifugal force of an exploding bomb.

Painted in 1941 in response to World War Two, Martial Memory was, he considered, his first mature work. Five boys play at war. Wearing pointy paper helmets and using sticks for guns and dustbin lids for shields, they form a tightly knit but joyless cluster of souls that Guston described as “lost, agonised beings”.

Painted in 1941 in response to World War Two, Martial Memory was, he considered, his first mature work. Five boys play at war. Wearing pointy paper helmets and using sticks for guns and dustbin lids for shields, they form a tightly knit but joyless cluster of souls that Guston described as “lost, agonised beings”.

Gradually, the paintings become more abstract and within a decade, Guston had abandoned figurative art for the abstract compositions which brought him fame and led, in 1962, to a retrospective at New York’s Guggenheim Museum. The transformation began in Rome during a residency at the American Academy. The only work he kept from that difficult period was a little ink sketch made on the beach in Ischia, an island in the bay of Naples, of white houses with black windows in the nearby village. Several years later those patches of light and dark had matured into what became his signature style – red, blue, green or grey brush marks grouped together in clusters which, despite their abstraction, still remind one of figures huddled together as in a rugby scrum (pictured below right).

Gradually the colour began to drain away, leaving a sea of grey and white brush marks surrounding a black shape that Guston increasingly thought of as a self-portrait – a call to arms, as it were, for someone engaged with politics yet producing apolitical work. And as demonstrations against the Vietnam war increased, he began asking himself: “What kind of man am I… going into a frustrated fury about everything – and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue?”

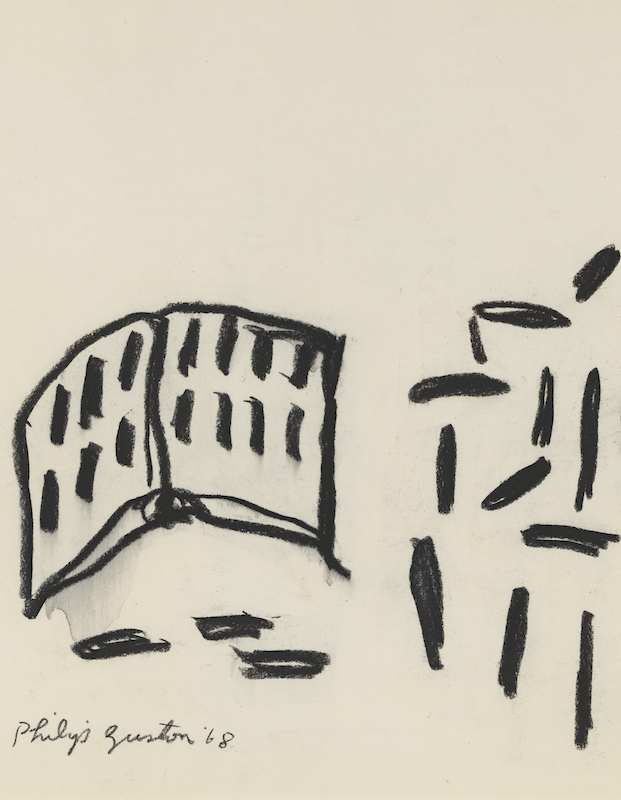

There followed 18 months of anguish during which he stopped painting and began producing simple line drawings in which something resembling a silhouette, a horizon or a drawing book and sticks of charcoal stutter into view (pictured above left: detail). Then in 1970, he took the art world by storm with a show at the Marlborough Gallery, which revealed to horrified friends and colleagues that he had returned to making figurative pictures.

There followed 18 months of anguish during which he stopped painting and began producing simple line drawings in which something resembling a silhouette, a horizon or a drawing book and sticks of charcoal stutter into view (pictured above left: detail). Then in 1970, he took the art world by storm with a show at the Marlborough Gallery, which revealed to horrified friends and colleagues that he had returned to making figurative pictures.

A bank of small paintings of mundane objects including a light bulb, a mug, boot, car, hooded figure and tenement block were painted in a style reminiscent of the Krazy Kat cartoons he’d loved as a kid. For one of their kind to switch from abstraction to making determinedly stupid and low brow pictures, at a time when figurative art was considered dated and retrograde, felt like an insult, a betrayal.

Later these pictures came to be seen as Guston’s “visual alphabet”, images he would return to again and again (pictured below: Flatlands, 1970). The inclusion in this retrospective of the early pictures allows one to see that this was not a new departure so much as a return to motifs like the pointy helmets, dustbin lids and tenement blocks which first appeared in Martial Memory some 30 years earlier.

And they continue to appear as the paintings gradually get larger, simpler and more emblematic. Aegean 1978, for instance, consists of an expanse of blue sky over blood coloured earth. Wielding dustbin lids, five hands reminiscent of those five boys fighting, clash against one another in the cloudless sky.

And they continue to appear as the paintings gradually get larger, simpler and more emblematic. Aegean 1978, for instance, consists of an expanse of blue sky over blood coloured earth. Wielding dustbin lids, five hands reminiscent of those five boys fighting, clash against one another in the cloudless sky.

Cartoon imagery is not used to make light of bitter truths but to confront things that otherwise might be unbearable. Haunted by photographs taken at Auschwitz concentration camp, he repeatedly paints stacks of abandoned shoes and legs heaped into piles as monumental as Stonehenge which, despite wearing hobnail boots, seem flaccid and powerless.

He also portrays the artist as powerless and irrelevant; a single-eyed stumble bum, he lies in bed puffing a cigarette and eating chips smeared with blood-red ketchup while trying to paint one of those mounds of shoes (main picture). “The paintings aren’t pictures, but evidences”, he once wrote, “maybe documents along the road you have not chosen, but are on nevertheless.”

For him painting was not a choice but a calling. In a moving portrait he shows himself and his wife Musa McKim lying in bed surrounded by a sea of darkness. Clutching his brushes as if his life depends on them, he curls up beside her like a child desperately seeking reassurance.

There’s always God to give us guidance. Out of a blue cloud, His hand appears brandishing a piece of charcoal with which He draws a line on the ground. Is this lesson in penmanship an edict, indicating a line in the sand that we may not cross? (pictured above left) “A picture should tell stories”, Guston wrote, but he also said “the trouble with recognisable art is that it excludes too much. I want my work to include more. And “more” also comprises one’s doubts about the object, plus the problem, the dilemma, of recognising it.”

His choice of cartoon imagery seems to me to be a way of having his cake and eating it. It allowed him to create recognisable objects that, because of their absurdity, are fundamentally paradoxical. A cartoon hand of God laying down the law is ludicrous, but compelling. It embodies the dilemma and accommodates the doubt, while also being a fabulously striking image.

His choice of cartoon imagery seems to me to be a way of having his cake and eating it. It allowed him to create recognisable objects that, because of their absurdity, are fundamentally paradoxical. A cartoon hand of God laying down the law is ludicrous, but compelling. It embodies the dilemma and accommodates the doubt, while also being a fabulously striking image.

At a time when all certainties have gone out the window, Guston’s late work continues to grow in popularity. The ambiguity of his approach seems the only sensible way forward.

- Philip Guston is at Tate Modern until February 25th 2024

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment