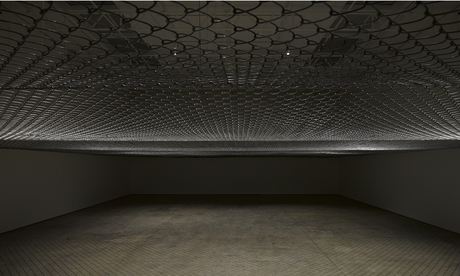

Perhaps my big mistake was to read the exhibition blurb before going in: as someone who worries about dark, confined spaces, I was anticipating Miroslaw Balka’s new installation with a perverse sort of excitement. Certainly, for anyone who enjoys a dose of controlled terror Above your head sounds promising, with White Cube’s basement gallery supposedly transformed into a “large cage” and the ceiling lowered to a claustrophobic two metres. Disappointingly, however, the thrill was entirely in the anticipation.

As someone particularly susceptible to the sensations the Polish artist has tried to induce, the inadequacies of the installation seem obvious: the chicken wire ceiling (pictured below) leaves perfectly visible the true, generous dimensions of the space, while the chatter of the gallery staff at the door provides a reassuring lifeline back to the real world. In fact, far more upsetting to one’s equilibrium is the whistled theme tune to The Great Escape, looped interminably from a source concealed somewhere in the gloom. In a rather ho-hum way, this tune, in this dark, comfortless space, reinforces the notion of imprisonment by introducing the possibility of escape, evoking the grim optimism of men digging their way to far from certain freedom.

the enigmatic trapezohedron appears to have no function other than as an off-the-shelf layer of implied meaning

The corollary, then, is to interpret the concrete sculpture on the floor of the upstairs gallery as the sealed exit point of a tunnelled escape route – Tom, Dick or Harry, if you will. If this all seems a little too much like a Great Escape re-enactment, the artist himself would seem to concur, surely the only explanation for the upper gallery’s second sculpture, a concrete, roughly diamond-shaped, hood-like box. The trapezohedron, for that is its proper name, is in fact a venerable motif and it is this bizarre, hulking object that dominates the background of Dürer’s Melancolia I, 1514.

The enigmatic trapezohedron appears to have no function for Balka, other than as a sort of off-the-shelf layer of implied meaning, and it pops up again in the companion exhibition running at the Freud Museum. This time it is in amongst the plywood boxes of We still need, a sculpture installation in one of the upstairs rooms of the Hampstead house that was, briefly, Freud’s home.

Freud was in poor health when in 1938 he fled to London to escape the Nazis, and he died here a year later, aged 83. While Freud was able to escape, three of his sisters would die at the Treblinka concentration camp, and it is this personal tragedy that Balka alludes to, his installation based on a letter listing items still needed for the construction of the Treblinka camp. Balka claims to have calculated the size and number of boxes to provide exactly the capacity needed to contain these items, but this information is not only easily missed altogether, it feels superfluous to the installation as we stand in front of it. The Treblinka reference, while clearly connecting it to Freud in the most chilling manner, needs far too much explanation to be considered satisfactory: it requires two pages of printed information for the viewer to “get it”.

Freud was in poor health when in 1938 he fled to London to escape the Nazis, and he died here a year later, aged 83. While Freud was able to escape, three of his sisters would die at the Treblinka concentration camp, and it is this personal tragedy that Balka alludes to, his installation based on a letter listing items still needed for the construction of the Treblinka camp. Balka claims to have calculated the size and number of boxes to provide exactly the capacity needed to contain these items, but this information is not only easily missed altogether, it feels superfluous to the installation as we stand in front of it. The Treblinka reference, while clearly connecting it to Freud in the most chilling manner, needs far too much explanation to be considered satisfactory: it requires two pages of printed information for the viewer to “get it”.

In truth, any sense of melancholy elicited by Balka’s installation is only really due to the way that the boxes look so like packing crates, suggesting Freud’s hurried flight from Austria. Balka’s ham-fisted attempt to summon up the memory of the Holocaust here of all places, and in such macabre style, seems a gross insensitivity; the whistling is here too, and in the calm of the house that was Freud’s sanctuary, it too feels like an intrusion.

Having two exhibitions running concurrently at quite different sites shows how reliant Balka is on the atmosphere and sense of history at the Freud Museum, in contrast to the blank canvas of White Cube. The White Cube show is formulaic and literal, and as obedient viewers our job is to simply join the dots. We still need does have a certain melancholy about it that, nevertheless, seems to have less to do with the quality of Balka’s work than the fertile atmosphere of Freud’s house, which is much as he left it, his study still containing the famous couch, and his extensive collections of books and artefacts.

Balka’s desperate clutches at meaning carry through to the shows’ titles, Die Traumdeutung 25,31m AMSL at White Cube and Die Traumdeutung 75,32m AMSL at the Freud Museum, which take the German title of Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams followed by each location’s height above sea level. He also considers significant the words contained within the German title, "die" for instance, and "trauma". In a bizarrely apposite case of life triumphing over art, the most meaningful aspect of Balka’s project is entirely unintentional: the sinister case of the “disappeared” Y-Chromosomal Adam, his black inflatable tower that was briefly in the Freud Museum’s front garden, but is no more. Apparently the neighbours complained.

- Miroslaw Balka at White Cube Mason's Yard until 31 May and at the Freud Museum until 25 May

Add comment