The first major retrospective of the videos, photographs and sculptures of Gillian Wearing is a deeply disturbing experience. Her videos can be just a few minutes, or as long as an hour, but are not sequential narratives. They can be dipped in and out of - unlike many video artists you do not have to acquiesce to her time scale. But take a lot of time: they are more than worth it, and repay repeated viewings.

Throughout she plays with notions of truth and deception. People speak with voices not their own; in later work both her subjects and her accurately entitled self portraits are masked with a prosthetic rubber face, moulded and sculpted by the artist.

In the space of just under five minutes a whole family dynamic is laid bare

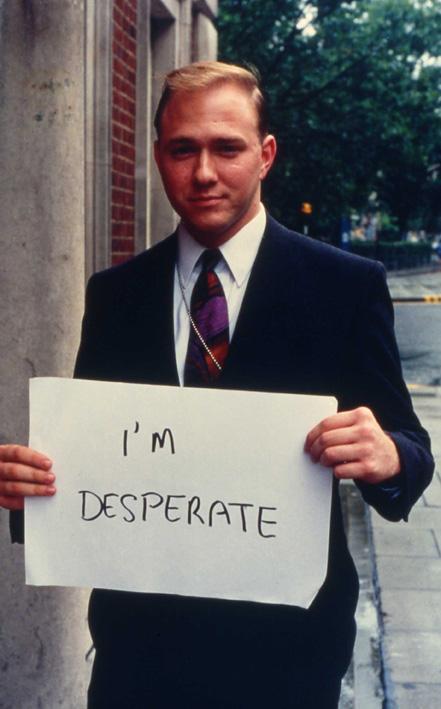

And masking is what it is all about. The clues are in the titles, from the earliest work on. One of the best known is one of the earliest, Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else wants you to say (phew!) 1992-1993, are street portraits of people. It is a miniature sociological dream in the diversity so nonchalantly exposed, differences subtly indicated by clothes, pose and attitude. Each holds a piece of paper with a handwritten phrase expressive of hitherto unexpressed thought: banal, extreme, vapid, meaningful, despairing, and often at odds with outward appearance. A young black policeman’s sign simply says HELP. A handsome besuited young man shows us that I’M DESPARATE (sic; main picture). The gap between the inward and the outward, the interior and the exterior, is here graphically displayed.

Gillian Wearing masks to reveal, disguises to lay bare. What she provides is a wholly unexpected tour de force: the spectator is disarmed by the visual vocabulary we are all familiar with from documentary films, photo essays and the like. But nothing is quite what it seems. 2 into 1, 1997 (pictured above and video clip below) is a video which shows us twins, boys of about 10, seen together once, but mostly on their own, and in a separate film their mother sitting alone: the mother speaks her sons’ words in the voice of her sons’, and they, in turn, speak their mother’s observations in her voice, all in sequence but not in a narrative. The boys complain, of her inefficiency, her pretensions, too kind they say, which to them is a weakness; she speaks admiringly of their talents, she adores them, but remarks on their rudeness and almost deliberate cruelty, young males already putting down the female. The boys loll in their chair; the mother sits upright, anxious, hair untidy. In the space of just under five minutes a whole family dynamic is laid bare, and as Hilary the mother so poignantly remarks motherhood hovers on the border between love and hate.

Gillian Wearing masks to reveal, disguises to lay bare. What she provides is a wholly unexpected tour de force: the spectator is disarmed by the visual vocabulary we are all familiar with from documentary films, photo essays and the like. But nothing is quite what it seems. 2 into 1, 1997 (pictured above and video clip below) is a video which shows us twins, boys of about 10, seen together once, but mostly on their own, and in a separate film their mother sitting alone: the mother speaks her sons’ words in the voice of her sons’, and they, in turn, speak their mother’s observations in her voice, all in sequence but not in a narrative. The boys complain, of her inefficiency, her pretensions, too kind they say, which to them is a weakness; she speaks admiringly of their talents, she adores them, but remarks on their rudeness and almost deliberate cruelty, young males already putting down the female. The boys loll in their chair; the mother sits upright, anxious, hair untidy. In the space of just under five minutes a whole family dynamic is laid bare, and as Hilary the mother so poignantly remarks motherhood hovers on the border between love and hate.

Sometimes adult actors are used, as in 10-16, 1997, to mime the short narrations of children aged 10 to 16. We hear the child drunk, the dementedly happy school girl, the aggressive toughie, the hopeful matricide. The children are innocent, knowing, spirited, corrupt, already ruined, and persistently hopeful.

The emotional and physical distress evidenced here is profoundly distressing

Three pastel candy-coloured booths house three almost unbearable video pieces: Confess All On Video. Don’t Worry. You Will Be In Disguise. Intrigued? Call Gillian….(1994), Trauma. 2000, and Secrets and Lies , 2009. Talking heads behind their masks, only their eyes visible, describe in their own voices traumatic incidents that still haunt them – abused childhoods, criminal acts, obsessive sexual needs, events that are in the past but dominate the present and shadow the future. Just occasionally among the score or so people in the three different groupings (the titles of each composite work indicate the category of each individual monologue) there is a gleam of redemption and recovery. The emotional and physical distress evidenced here is profoundly distressing, but the visitor does not feel voyeuristic. The people here are volunteers, complicit and compliant to their filming. What comes across vividly is Wearing’s dispassionate interest. There are of course none of the protocols of psychotherapy, or even sociology or anthropology. She is on a voyage of discovery, and it is no business of hers to give aid and succour; that is up to the subject. But the examined life is worth living.

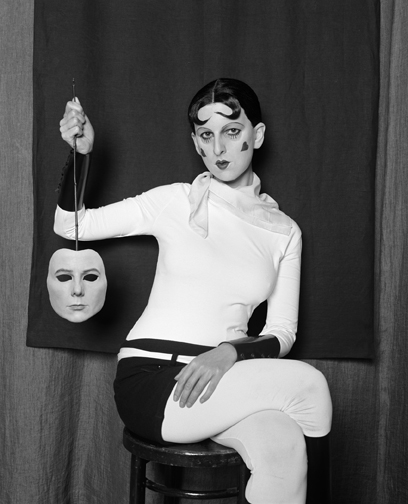

Of course, Wearing puts herself through it, too. Covering her face with the most elaborate, painstaking, terrifyingly realistic protheses, she has made a series of self-portraits as the photographers she admires, those obsessed with people often at the extreme end of things, from Diane Arbus, to Andy Warhol, to Robert Mapplethorpe and August Sander, and the wonderful solipsist, Claude Cahun (pictured right), who also photographed herself obsessively in various guises. Wearing takes herself on as well, aged 3, 17, as an adult, and provides a series of self-portraits as members of her own family – grandparents, parents, uncle, sibling – only her own eyes speaking to us from without the mask.

Of course, Wearing puts herself through it, too. Covering her face with the most elaborate, painstaking, terrifyingly realistic protheses, she has made a series of self-portraits as the photographers she admires, those obsessed with people often at the extreme end of things, from Diane Arbus, to Andy Warhol, to Robert Mapplethorpe and August Sander, and the wonderful solipsist, Claude Cahun (pictured right), who also photographed herself obsessively in various guises. Wearing takes herself on as well, aged 3, 17, as an adult, and provides a series of self-portraits as members of her own family – grandparents, parents, uncle, sibling – only her own eyes speaking to us from without the mask.

Gillian Wearing at Whitechapel Gallery until 17 June

Watch a video clip of 2 into 1

Add comment