The Imperial War Museum is one of the most extraordinary museums in the world. Its contents and presentation triumph over the three words of its title, each usually causing dread rather than enthusiasm: imperial (discredited unless to do with Roman history); war (just horrible, and we shouldn’t do it); and museum (well, isn’t that mausoleum?)

In fact, its collections embrace the modern world, and are perhaps the most insightful and visible tour of modern history that we have.

The IWM was founded by the government in 1917 to tell and show us descriptions – through archives, diaries, oral and written testimony, imaginative fiction and poetry, objects from planes to bombs, photography, film, television, fashion, and fine art – of all the conflicts with which Great Britain and its empire have been involved from the First World War on.

Vehicles and weapons of all sorts look as though they are about to hurtle forth from the floors above

As at the turn of the last century one in four of the world’s population lived in the British Empire or British sphere of influence, so the museum’s remit is global. In the first of the permanent galleries that have been added to tell the story of the Great War, we are reminded by a fascinating sequence of film and photographs of civic life that, just before its outbreak, one percent of the population owned 70 percent of Britain’s wealth, 12 was the school leaving age, and life expectancy was about 50 for men and 55 for women.

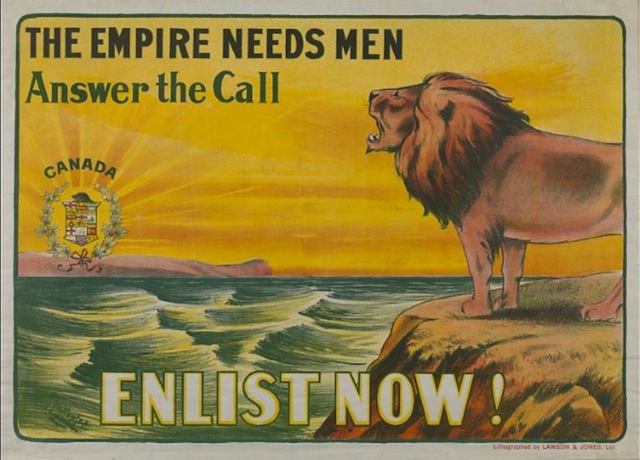

Women of course did not yet have the vote but one of the unintended consequences of the global calamity was that, for practical reasons as more and more women entered the work force at all levels, the fight for their civil rights gained momentum. It was during the war that women first entered the police force. Emotive photographs and film from the time tell the stories. (Pictured below: WW I Canadian recruitment poster)

The redesign of the atrium, adding another floor, the creation of the new World War I galleries, and the refurbishment and new arrangements for other galleries has been four years in planning and execution, costing some £40m. The dramatic yet austere reimagining of the architecture by Foster and Partners (also responsible for the American Air Museum at Duxford in 1997) and the unusually clear interior design by Casson Mann, are at the service of showcasing with as much clarity as possible hugely complex stories. The narratives of the past were rethought by the IWM’s own team of historians and curators, and academics from outside.

The redesign of the atrium, adding another floor, the creation of the new World War I galleries, and the refurbishment and new arrangements for other galleries has been four years in planning and execution, costing some £40m. The dramatic yet austere reimagining of the architecture by Foster and Partners (also responsible for the American Air Museum at Duxford in 1997) and the unusually clear interior design by Casson Mann, are at the service of showcasing with as much clarity as possible hugely complex stories. The narratives of the past were rethought by the IWM’s own team of historians and curators, and academics from outside.

The result embodies the shifts in current historiography, reflecting the explosion in the writing of 20th-century history in the past several decades. The history is told of course in three dimensions, with essential captions in a marriage of object and text.

Rather like the Great Court of the British Museum, (by the same architects) it is the drama of the four-storey atrium that sets the scene, and articulates the physical organisation of the collections. It is framed by two vertiginous staircases – there are four lifts behind the far staircase – which underline the theatrical framing. Containing some 400 large objects, with a Harrier Jump Jet, V2 rocket and Spitfire all suspended from above it providies the "wow factor". Vehicles and weapons of all sorts look as though they are about to hurtle forth from the floors above. Down to earth is a disturbing heap of rusted metal: the remnants of a blown-up car from Baghdad, the detritus of a suicide bomber. It’s a macabre “ready-made” bought to us by Jeremy Deller.

Entering from the ground floor of the atrium there are 14 new galleries devoted to the First World War – some 1,300 objects, 60 computerised cinema, film and visitor interactive installations – divided into sections which indicate the inevitable and appalling sequence of events, from "Hope and Glory" to "War Without End", and the coda of the failed and vengeful peace process. The galleries show us the first truly global war, and the first industrial and industrialised war. Some of the most startling images are a series of photographs of the massive home front munitions factories, like huge installations, with endless rows of shells.

Major masterpieces from the incomparable collection of war art, including Paul Nash’s The Menin Road (pictured above), are interwoven with photographs of the home front and the war front, films and documentaries, uniforms, weapons, a replica trench, cartoons, posters, newspapers, and such things as a fake tree which was a lookout post. The barrage of facts is very well paced, so that a plethora of images is succeeded by an interactive installation or a pause to watch a film.

Major masterpieces from the incomparable collection of war art, including Paul Nash’s The Menin Road (pictured above), are interwoven with photographs of the home front and the war front, films and documentaries, uniforms, weapons, a replica trench, cartoons, posters, newspapers, and such things as a fake tree which was a lookout post. The barrage of facts is very well paced, so that a plethora of images is succeeded by an interactive installation or a pause to watch a film.

Surprisingly, too, there is, for once in a museum, a genuinely enhancing and atmospheric soundscape, sometimes muted explosions, sometimes music, sometimes silence. There is a restored version of a long documentary made at the time of the Battle of the Somme; there are the packaging and tins of wartime food for the soldiers; and a replica of a trench over which a tank hovers. Orpen’s study of The Signing of Peace in the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles depicts those men in suits and uniforms who went on squabbling, it seems, for ever. A complementary video shows not only who was who but what, from Lloyd George to Woodrow Wilson to Clemenceau, they all really thought of each other.

On the third floor we find Truth and Memory, a selection from IWM’s incomparable collection of First World War art. There’s a room devoted to John Singer Sargent’s Gassed (pictured above), a frieze of suffering, blinded soldiers – poison gas was used in 1915, at first by the Germans – with, in the far distance, a football game being played by soldiers still almost whole. Even the Vorticists, enthralled briefly by the machine age, are witness to the terrible consequences, with Wyndham Lewis’s huge masterpiece, A Battery Shelled. Stanley Spencer turned his artistic skills to his great painting of the Eastern Front, the wounded on stretchers at a dressing station in Macedonia. There are women artists too, of sensitive gifts: Anna Airey’s superbly done small paintings of women at work in the weapons factories. A special gallery for IWM Contemporary shows a remarkable new series of giant photographs of Afghan civilians, children, and soldiers, from Helmand, and a series of edgy and beautiful films by Mark Neville.

On the third floor we find Truth and Memory, a selection from IWM’s incomparable collection of First World War art. There’s a room devoted to John Singer Sargent’s Gassed (pictured above), a frieze of suffering, blinded soldiers – poison gas was used in 1915, at first by the Germans – with, in the far distance, a football game being played by soldiers still almost whole. Even the Vorticists, enthralled briefly by the machine age, are witness to the terrible consequences, with Wyndham Lewis’s huge masterpiece, A Battery Shelled. Stanley Spencer turned his artistic skills to his great painting of the Eastern Front, the wounded on stretchers at a dressing station in Macedonia. There are women artists too, of sensitive gifts: Anna Airey’s superbly done small paintings of women at work in the weapons factories. A special gallery for IWM Contemporary shows a remarkable new series of giant photographs of Afghan civilians, children, and soldiers, from Helmand, and a series of edgy and beautiful films by Mark Neville.

The whole is not only an astonishing history lesson, but a formidable exposition of those contradictory aspects of the events and the individuals at the core of this history: the surprising humour as well as the idealism and cynicism that accompanied both participation and survival, and the inevitable terror and pity. Take not one day but several, and of course there are three new shops and two new cafés.

Add comment