Edward Weston, Chris Beetles Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Edward Weston, Chris Beetles Gallery

Edward Weston, Chris Beetles Gallery

Perfectionism works, from toilets to cabbages to nudes

But he was also, during the early years of this collection of 37 prints (1920s to 1945), heavily influenced by the ideals of Modernism, and stuck close to its mantra, “Form follows function”. The lavatorial subject was not typical; he is best-known for the exquisite – and perfect – nautilus Shell, 1927 (pictured below), the erotically deformed Pepper, 1930, vast pictorial landscapes of Arizona and the female nudes.

Weston’s criterion of beauty is fascinatingly extreme. From toilet to nautilus is a giant leap. Shooting the shell "face" on using, as always, natural light, he captures a beam reflected back off the curved surface and convincingly revealing its hard, brittle texture. The eye is drawn over the curved hump, down towards the interior which radiates an almost celestial light. Apart from its textural beauty, the shape and form is perfection (a vintage print sold for over $1 million in 2007) but of course, that’s nature’s skill. It’s tempting to suggest that had Weston not fallen for photography, he would have been a sculptor (he admitted inspiration from photographs he saw of Brancusi’s work).

Weston’s criterion of beauty is fascinatingly extreme. From toilet to nautilus is a giant leap. Shooting the shell "face" on using, as always, natural light, he captures a beam reflected back off the curved surface and convincingly revealing its hard, brittle texture. The eye is drawn over the curved hump, down towards the interior which radiates an almost celestial light. Apart from its textural beauty, the shape and form is perfection (a vintage print sold for over $1 million in 2007) but of course, that’s nature’s skill. It’s tempting to suggest that had Weston not fallen for photography, he would have been a sculptor (he admitted inspiration from photographs he saw of Brancusi’s work).

His depiction of other natural objects included the elegant Cabbage leaf, 1931, whose fanned out, velveteen folds connect to classical painters’ compulsion to represent form through richly textured, folded fabrics. He seems to link that to the undulating waves in rock formations and sand dunes, most perfectly captured at Zabriskie Point, 1938, in a scene of geological poetry.

On the other hand, the famously erotic pepper is unsubtle. Printed under sultry lighting, it possesses a musky sensuality and is imitated by a nude model bent over so that stomach, breast, arms and thighs are squashed together in imitation of the plump, curvaceous vegetable. Headless and impersonal, it is an object study compared to the human connection with the full-figure nudes.

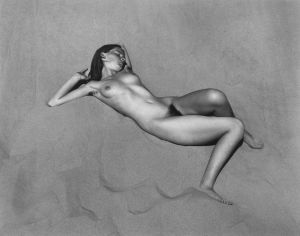

The magnificent Nude on Sand, Oceano, 1936 (pictured below), sees the young woman sprawled on hot sand which fills the frame. Eyes closed in private reverie, she is inaccessible to the staring lens and photographer’s eye, making her, in terms of "the male gaze", more desirable. Nude, New Mexico, 1937, shows a suprising hint of sexual symbolism: the same model lies on a dark blanket, hands covering her eyes, the darkness repeated in her pubic hair and in the gaping mouth of a cave behind her.

Weston was known for his many model-lovers and he saw the erotic everywhere, long before that was the norm in our sexualised world. His most significant, the Italian photographer Tina Modotti, suggested that his photographs possessed "an erotic quality" but he denied seeing it when selecting or shooting the subjects. And actually, his approach was heavily theoretical whilst creating some of the warmest, most sensual - and erotic - imagery of his day. But their honesty and sometimes profundity proved that he succeeded in depicting what he searched for, "the quintessence of the object or element before my lens". The quest, of course, continued in the dark room, and these second-generation prints from the original negatives, are no less perfect - produced by Cole Weston according to his father’s dictation.

Weston was known for his many model-lovers and he saw the erotic everywhere, long before that was the norm in our sexualised world. His most significant, the Italian photographer Tina Modotti, suggested that his photographs possessed "an erotic quality" but he denied seeing it when selecting or shooting the subjects. And actually, his approach was heavily theoretical whilst creating some of the warmest, most sensual - and erotic - imagery of his day. But their honesty and sometimes profundity proved that he succeeded in depicting what he searched for, "the quintessence of the object or element before my lens". The quest, of course, continued in the dark room, and these second-generation prints from the original negatives, are no less perfect - produced by Cole Weston according to his father’s dictation.

For the final years of the show, Weston took deeper journeys into America’s near empty landscapes, and produced some very different works. Iceberg Lake, 1937, comes close to abstract painting, and the eponymous Abandoned Shoes, Alabama Hills, 1937, alludes to a human presence and hints of the fading Depression not far from home. Weston was a dreamer, floating on his art, while Dorothea Lange documented human tragedy. But that was his choice, and the results are there to prove the value of someone so dedicated to perfection. The exhibition’s closing image, Winter Idyll, 1945, sees a young nude woman on a swing against a landscape resembling Tuscany – an idyll marking the end of the War.

- Edward Weston at the Chris Beetles Gallery until 25 September

- View Edward Weston's work

- Find Edward Weston on Amazon

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment