Billed as “a journey through painting and photography”, Capturing the Moment reveals many ways in which artists have responded to photography – either by taking up the camera themselves, as did Candida Höffer, Andreas Gursky, Louise Lawler and Thomas Struth, or by making some superb paintings.

By way of introduction, the first room makes no sense, though. Picasso once said – probably as a riposte to anyone criticising his disregard for surface appearances – “photography has arrived at a point where it is capable of liberating painting from all literature, from the anecdote, and even from the subject. So shouldn’t painters profit from their newly acquired liberty to do other things?” And true to his word, in The Weeping Woman 1937 he portrays Dora Maar from several viewpoints at once.

So far so good; but then comes a single photograph – Dorothea Lange’s famous photo of a share cropper’s family – as though it alone could represent the medium, which is ludicrous. The presence of Alice Neal is mystifying, since her idiosyncratic portraits owe nothing to photography, so is the inclusion of Lucien Freud. Rather than following Picasso’s advice, Freud scrutinised his subjects with an unwavering eye, as though determined to outdo the camera’s forensic potential.

So far so good; but then comes a single photograph – Dorothea Lange’s famous photo of a share cropper’s family – as though it alone could represent the medium, which is ludicrous. The presence of Alice Neal is mystifying, since her idiosyncratic portraits owe nothing to photography, so is the inclusion of Lucien Freud. Rather than following Picasso’s advice, Freud scrutinised his subjects with an unwavering eye, as though determined to outdo the camera’s forensic potential.

This incoherent start doesn’t bode well; but as you progress from room to room, things get better and better. And the large central space is hung with paintings by some of the best contemporary artists around. All are based on photographs which, when translated into paint, somehow reveal the corruption lurking beneath beguiling appearances.

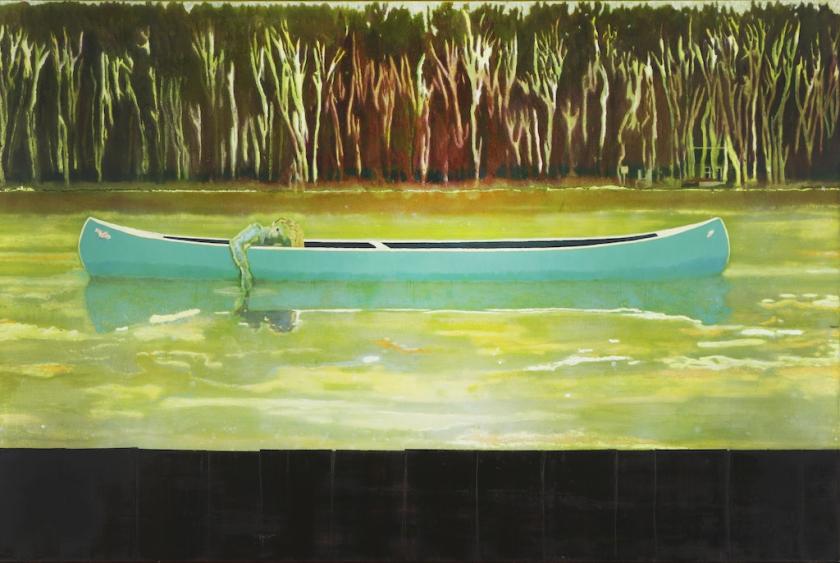

Based on a still from the horror film Friday 13th 1980, Peter Doig’s Canoe Lake, 1998 (main picture) at first appears elegiac. Up close, though, you notice that the canoeist is slumped over in a gangrenous heap, there’s a ghostly house huddled in the oppressively dark forest and the green water looks acidic enough to dissolve human bones.

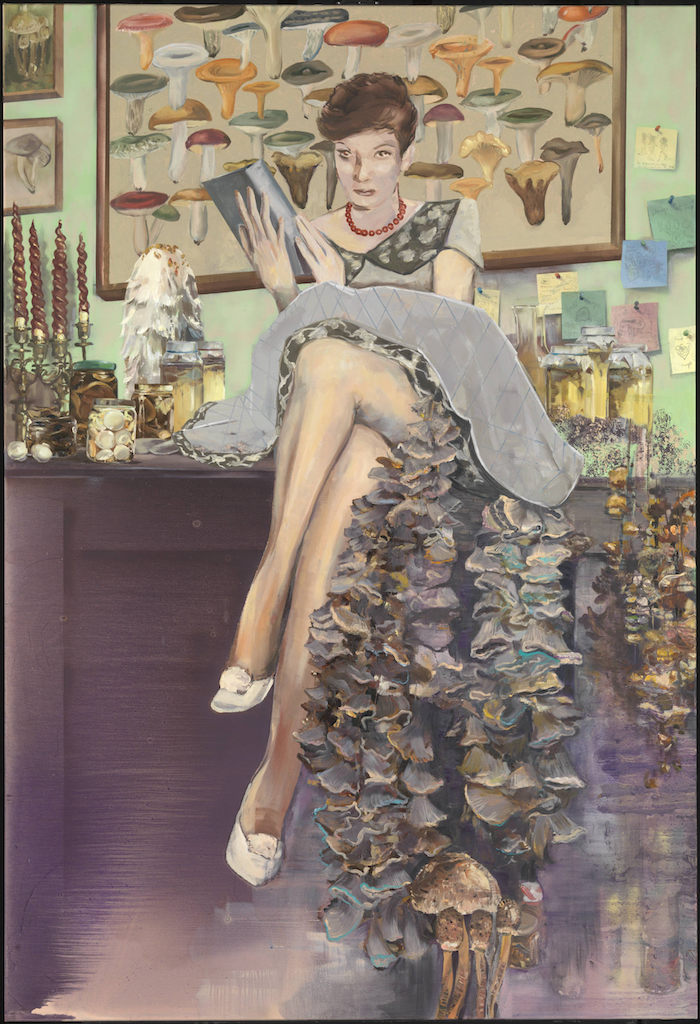

In her painting The Alchemist 2015 (pictured above right), Paulina Olowska parodies the erotic polaroids taken by Italian architect, Carlo Molino. She perches atop a dresser, her skirt drawn up to reveal her thighs and a cascade of fungi trailing down her leg like a frilly petticoat. Pictures of mushrooms cover the wall behind her, while phallic candlesticks and waves of melted candle wax draw visual parallels between ejaculations and those frills of fungal growth. It’s very mysterious, but utterly compelling.

Prompted by photographs of immigrant boats capsizing in the Mediterranean, Miriam Cahn’s The Beautiful Blue 2017 (pictured left) is an eerie evocation of drowning bodies floating underwater in a deathly calm.

Prompted by photographs of immigrant boats capsizing in the Mediterranean, Miriam Cahn’s The Beautiful Blue 2017 (pictured left) is an eerie evocation of drowning bodies floating underwater in a deathly calm.

Marlene Dumas’s Stern 2004 is based on a photograph published in Stern magazine. She portrays Ulrike Meinhof, a member of the anarchist group, Red Army Faction, after being hanged in her prison cell either by herself or a murderer. Going in close on her pale skin, Dumas portrays her lifeless head as if it were a mountain range, a monument to hideously misguided ambitions.

Gerhard Richter's Tante Marianne 1965 is especially poignant. Based on a black and white snapshot of the 4 month old artist sitting in the lap of his smiling young aunt, it is painted in monochrome. Before the paint had fully dried, the image was slightly smudged to suggest the fading of a memory through time, but also to reflect the death of this beautiful girl at the hands of the Nazis.

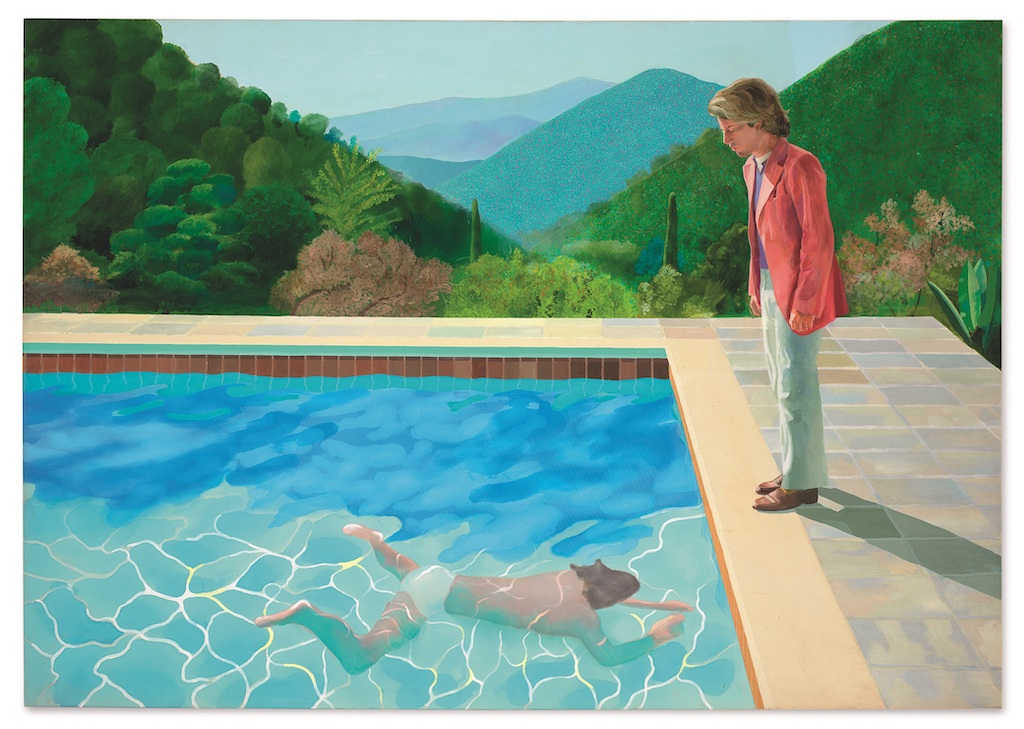

David Hockney’s gloriously sunny Portrait of an Artist, 1972 (pictured below) is also included. Based on his own photographs, it shows his then boyfriend Peter Schlesinger gazing into the limpid depths of the pool where his assistant John St Clair is swimming underwater. A few years later Hockney became obsessed with photography and began making elaborate collages, which he called joiners and involved juxtaposing myriad shots of the same scene.

Any serious look at the relationship between painting and photography would feature them, but this show doesn’t pretend to be an overview. Instead, it’s a celebration of the work in the YAGEO Foundation Collection, which was founded in 1999 by Taiwanese entrepreneur Pierre Chen. Along with a deep pocket, Chen must have either an unerring eye for excellence, or a first rate advisor, or both, because his holdings are especially fine and we are incredibly lucky that he has loaned so many to the Tate.

The selection of pictures often seems arbitrary or random, but if you forget about curatorial rigour and just enjoy the many brilliant paintings on show, the exhibition is an absolute delight. Tate Modern has augmented YAGEO’s first class loans with work from their own collection so as to weave a loose thread or, as they call it, an “open-ended discussion” concerning artists’ responses to photography.

The selection of pictures often seems arbitrary or random, but if you forget about curatorial rigour and just enjoy the many brilliant paintings on show, the exhibition is an absolute delight. Tate Modern has augmented YAGEO’s first class loans with work from their own collection so as to weave a loose thread or, as they call it, an “open-ended discussion” concerning artists’ responses to photography.

- Capturing the Moment is at Tate Modern until 28th January 2024

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment