It’s not often that an exhibition makes me cry, but then it’s not often that a show reveals the degree to which we have been duped. Action Gesture Paint includes the work of some 80 women, half of whom I’d never heard of. Given that I’ve been a critic for over 40 years and consider myself well-informed, that’s pretty mind-boggling.

Where have these artists been hiding? Or, rather, who has been hiding them from us? No marks for guessing it was the male-dominated art establishment.

The period covered by this revelatory Whitechapel show is 1940-1970, when Abstract Expressionism swept the globe. The New York critic Harold Rosenberg heralded this gestural form of abstraction as a liberation. “At a certain moment,” he famously wrote in 1952, “the canvas began to appear to one American painter after another as an arena in which to act – rather than as a space in which to reproduce, redesign, analyze or 'express' an object, actual or imagined.” From then on gestural abstraction was perceived as a heroic encounter with the self. Painting was a form of toughing it out – no tinkering, no decorative flourishes – only the free flow of unadorned psychic truths; men being the only ones brave enough to confront the void of the canvas. Except it was macho bullshit.

From then on gestural abstraction was perceived as a heroic encounter with the self. Painting was a form of toughing it out – no tinkering, no decorative flourishes – only the free flow of unadorned psychic truths; men being the only ones brave enough to confront the void of the canvas. Except it was macho bullshit.

As this exhibition reveals, dozens of women were making strong, confident paintings every bit as exciting and dynamic as their male counterparts. Some enjoyed a degree of success when they were young, only to be ignored, forgotten or overlooked later on and written out of history.

I saw the exhibition during the installation, before the lighting was up and much of the work was in gloom. This twilight viewing seemed absolutely appropriate – a metaphor for the way the work of these remarkable women had been consigned to obscurity. A brown smudge – almost invisible in the dark – revealed itself (as my eyes adjusted) to be an explosive flurry of browns, reds, ochres and greys resembling a vase of flowers in dynamic motion. I’d never heard of the Chinese American artist Bernice Bing and wanted more of her incredibly exciting work, but with so many to include, there’s room for only one or two paintings per person, despite a very dense hang.

Now that everything is properly lit, a huge mixed show like this inevitably becomes a cacophony of competing voices. And having to let your eyes adjust to yet another sensibility is hard work and time-consuming; but with so many outstandingly good paintings on view, it is well worth the effort.

Now that everything is properly lit, a huge mixed show like this inevitably becomes a cacophony of competing voices. And having to let your eyes adjust to yet another sensibility is hard work and time-consuming; but with so many outstandingly good paintings on view, it is well worth the effort.

Some well-known names are present, of course. The show opens with April Mood, 1974 (main picture) an elegiac landscape by Helen Frankenthaler, which is to die for. Subtle washes of acrylic soak the canvas in bands of intense colour that evoke the roseate glow of dawn. Producing an image this beautiful without a shred of sentimentality requires genius. And the show closes with Untitled, 1957 by Joan Mitchell, another artist so good she was impossible to ignore. Arcs of magenta and green stack up over a white ground in gestural sweeps so vigorous that making them must have involved her whole body.

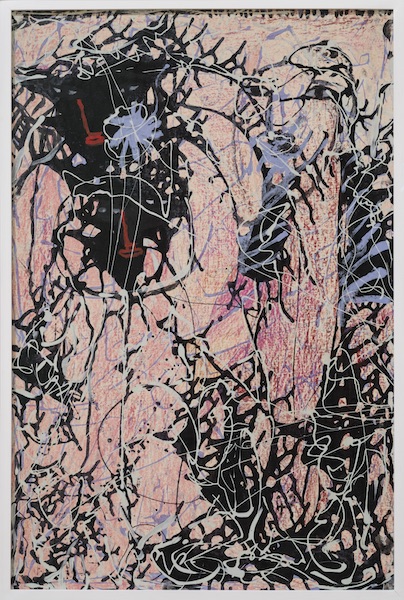

Grace Hartigan, another doyen of Abstract Expressionism, is represented by two large canvases whose gestural outpourings in black, orange, white and yellow are as powerful as a punch in the gut. The two works by Lee Krasner don’t convey her genius, but if you saw her Barbican retrospective you will know what a creative powerhouse she was. It’s exhilarating to see work by relatively well-known names, but even more exciting is the inclusion of so many unknown artists. Attacking the canvas with gusto, Korean painter Wook-Kyung Choi produced incredibly dynamic abstractions (pictured top, full column: Untitled 1960’s). “I dash into the canvas and develop various situations without any conception or any plan,” she wrote. “While doing all this, I select, organise and create order.” As her title Jump in and Move Around, 1961 suggests, American painter Amaranth Ehrenhalt similarly enjoyed diving in and orchestrating the balance between order and chaos.

It’s exhilarating to see work by relatively well-known names, but even more exciting is the inclusion of so many unknown artists. Attacking the canvas with gusto, Korean painter Wook-Kyung Choi produced incredibly dynamic abstractions (pictured top, full column: Untitled 1960’s). “I dash into the canvas and develop various situations without any conception or any plan,” she wrote. “While doing all this, I select, organise and create order.” As her title Jump in and Move Around, 1961 suggests, American painter Amaranth Ehrenhalt similarly enjoyed diving in and orchestrating the balance between order and chaos.

Lilly Fenichel fled the Nazi invasion of Austria and came to Britain before settling in California. The black shapes parading over the fierce yellow ground of Untitled, 1950 (pictured above, full column) are like harbingers of evil strutting their stuff in a drama of violence. In Judith Godwin’s imposing paintings, the arcs of black slicing through space were inspired by contemporary dance and a long association with New York choreographer Martha Graham. On a much smaller scale but no less dramatic, are a set of exquisite lithographs by Japanese artist and calligrapher Toko Shinoda. Combined with shafts of black, delicate brushmarks eloquently define space and suggest movement.

Born in Colombia in 1938 and living in New York, Fanny Sanin is one of the few artists here who is sill alive. Switching from oil to acrylic she produced hard-edged abstracts comprising clusters of vibrant colour in opaque and translucent washes (pictured above, right: Oil No. 4, 1968). At the other extreme are the multi-layered monochromes of Argentinian painter Sarah Grilo. Stencilled and hand-written letters and numbers evoke the signage, adverts and graffiti she encountered on the streets of New York, where she moved to in 1962.

Born in Colombia in 1938 and living in New York, Fanny Sanin is one of the few artists here who is sill alive. Switching from oil to acrylic she produced hard-edged abstracts comprising clusters of vibrant colour in opaque and translucent washes (pictured above, right: Oil No. 4, 1968). At the other extreme are the multi-layered monochromes of Argentinian painter Sarah Grilo. Stencilled and hand-written letters and numbers evoke the signage, adverts and graffiti she encountered on the streets of New York, where she moved to in 1962.

These voices are all highly individual; inevitably, though, some of the work is derivative. Lest you dismiss these brave women as followers rather than leaders, though, bear in mind the story of Janet Sobel. She changed the course of art history by working on the floor, dripping paint through glass eye droppers and vacuuming pools of wet paint into gossamer thin filigree (pictured above, left: Illusion of Solidity, c.1945). Having seen her paintings at Peggy Guggeheim’s gallery in 1945, Jackson Pollock appropriated her technique and, dubbed “Jack the Dripper”, happily accepted the mantle of pioneer of a technique he had purloined rather than invented.

In a nutshell, that is how history gets rewritten – over and over again. And the effect is poisonous. As an art student I was told there had never been any significant women artists, and I had no way of disproving this falsehood. Every day, though, female art historians are uncovering yet more evidence of women whose achievements have deliberately been hidden. Recently the genius of Artemisia Gentileschi was on view at the National Gallery that of Lee Krasner at the Barbican. And we now know that the first abstracts were painted by Hilma af Klint rather than Kandinsky.

Action Gesture Paint is a revelation and an inspiration. It is also an irrefutable demonstration of the extraordinary number of brilliant women from across the globe who were making abstract paintings in the 20th century. Let no ignoramus ever again try to claim that there have been no important women artists.

- Action Gesture Paint at the Whitechapel Gallery until 7 May

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment