The Kenwood Chef! Intercity 125! Kodak Instamatic! Wilkinson Sword disposable razors! Bus shelters! Parking meters! They were all designed by a British genius, Sir Kenneth Grange, who appeared here as the subject of a short and disarmingly confident interview, intiating a series of such interviews. The programme marked the opening weekend of the £83m transformation of the Grade2* redundant Commonwealth Institute in Kensington into the new Design Museum, which showcases both British and international contemporary design.

It was bookended with an interview with Sir Terence Conran, now 85. It was Conran whose Habitat shops transformed the middle class taste of the British, moving home furnishings from chintz to rush-seated rural kitsch kitchen chairs by Magistretti, and who may even have revolutionised (sic) our sex lives by bringing the duvet to Britain. His ad for the duvet showed a man making the bed in 20 seconds while his female partner carefully applied her makeup, presumably post-coital. And it was Conran, we were reminded, who thought up the Design Museum in the first place. It started its life in 1982 in the emptiness of the old Boiler Room in the Victoria and Albert, moved to a warehouse in Shad Thames (now to be the home of Zaha Hadid Architects), and now returns to genteel Kensington on the edge of Holland Park.

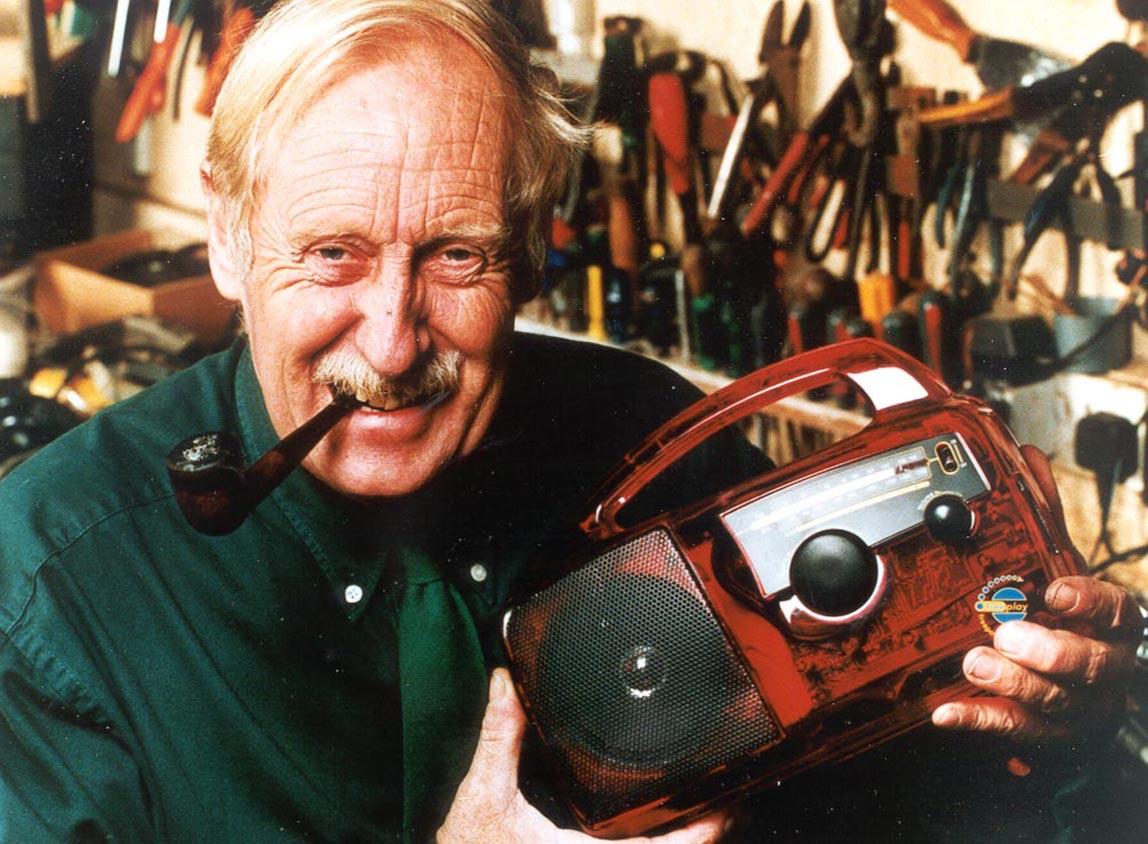

We were offered a serving of canapés when we wanted a real meal In between we met Trevor Baylis, whose inspiration – and we were shown the Heath Robinson workshop in which he figured it all out – was literally life-changing. For Africa, a continent where electricity can be intermittent and batteries hugely expensive, he invented nothing less than the wind-up radio. Vox-popped interviewees somewhere in shanty town Africa (what stereotypes this programme dabbled in) approved: they wanted loud music to come from a big heavy box. But the wind-up radio could convey information as complex as "beware of mine-filled fields", and "this is what you should know about HIV and Aids".

Baylis, interviewed at home on Eel Pie Island, was as amazing as his invention; he had been a champion swimmer, a stunt double, worked in a circus, had been an aquatic escape artist. He had realised the necessity for the Baylis radio when he had watched a television programme about AIDS in Africa, and the desperate need to convey factual information about the disease. His brilliant idea had languished until the notion was taken up on television’s Tomorrow’s World. Now Baylis (pictured below) has set up an organisation to pair inventors with business partners.

His invention was literally life-changing, as was that of David Constantine. He was permanently crippled when only 21 in one of those all too common freak accidents, diving into shallow water and breaking his spine. His misfortune led to public advantage, with his invention of a low cost and amazingly flexible wheelchair, and his charity called Motivation. Post-accident quadriplegic David went into IT, then got himself to the Royal College of Art, where he and fellow students set about rethinking the wheelchair. Now when you witness those astonishing games – basketball, say – played by wheelchair teams, those are the Constantine wheelchairs, wheeling and dealing.

Over 50 years ago the now octogenarian Margaret Calvert invented the road signage system still in use now, when motorways were first built in Britain, and those signs we see when crossing the road. The children’s sign showed in pictograph form a larger girl leading a smaller boy; cue presenter asking Ms Calvert if she thought herself a feminist, which led to a moment of interviewee speechlessness. I think the answer was no, although shehad amused herself by putting the girl in the lead.

Over 50 years ago the now octogenarian Margaret Calvert invented the road signage system still in use now, when motorways were first built in Britain, and those signs we see when crossing the road. The children’s sign showed in pictograph form a larger girl leading a smaller boy; cue presenter asking Ms Calvert if she thought herself a feminist, which led to a moment of interviewee speechlessness. I think the answer was no, although shehad amused herself by putting the girl in the lead.

As interview succeeded interview, there was a subtle underlining of hope for the design talents that might rescue Britain’s economy from potential post-Brexit recessions. But the programme inadvertently undermined its own case by telling us in brief the difficulties some of the self-motivated designers – those who were not initially commissioned by businesses, and even some who were – faced in getting their inventions from prototype to manufactured object.

What we were offered was a serving of canapés when we wanted a real meal: proper narratives for each designer, not snippets which somehow condescended to both interviewee and viewer. This programme did not have enough confidence in itself to persuade the audience of the genuine importance and interest of its subject, an attitude symbolised by digressing to an occasional celebrity for irrelevant comment.

Add comment