Lucky Will Young: the production of the Simon Stephens monologue Song from Far Away that he is delivering at the Hampstead Theatre is directed by Kirk Jameson, not Ivo van Hove.

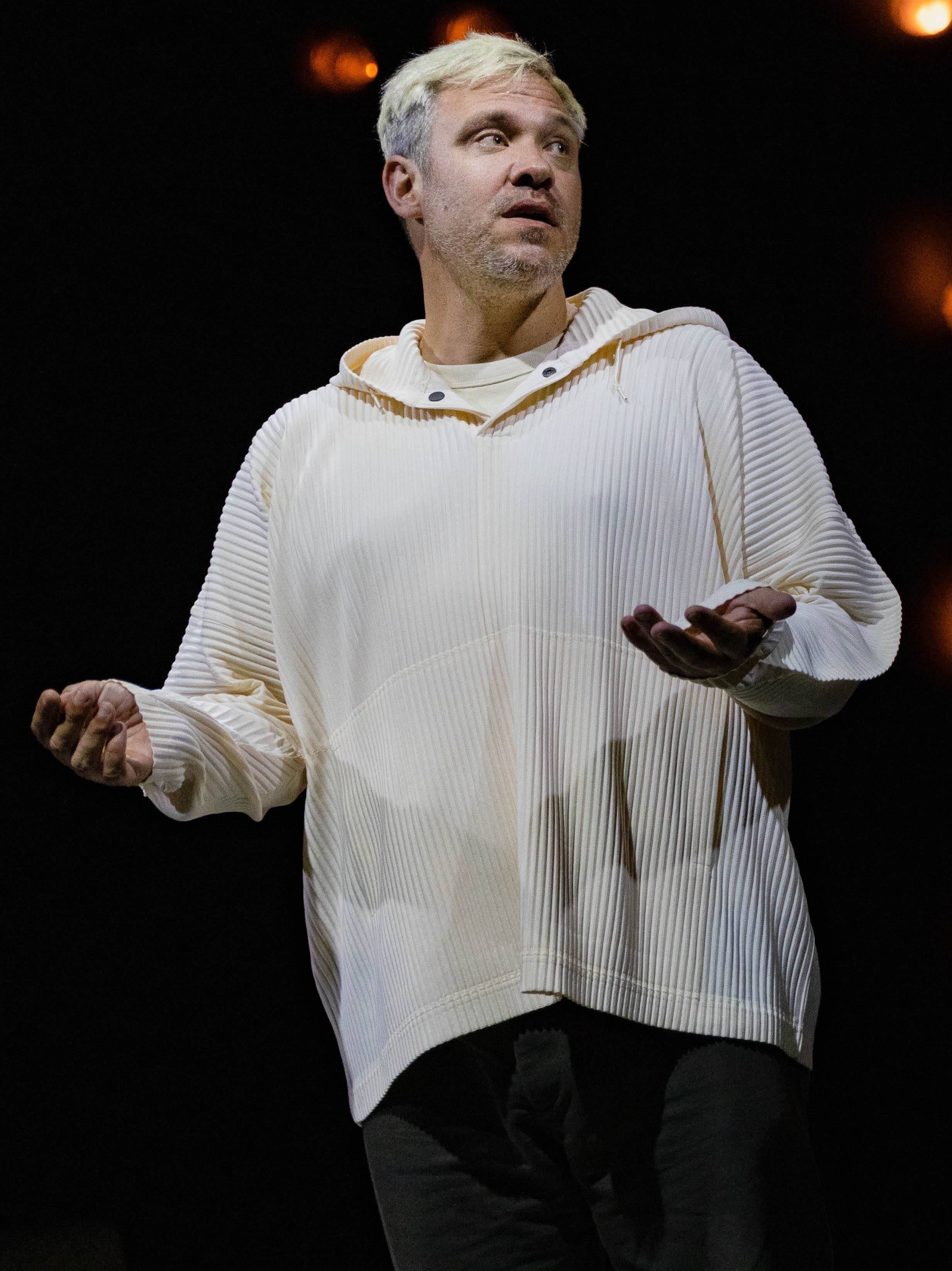

The modish Dutch director of the initial UK staging, seen at the Young Vic in 2015, stripped his actor naked for much of the performance. Young, though, is allowed a loose white shirt and black trousers throughout.

Van Hove’s literal laying bare of Willem was presumably a visual aid to what he thought the monologue was setting out to do. Willem is a hollow man: a determinedly private individual, a hedgie and transplanted Amsterdammer who relishes the plush anonymity of airport VIP lounges, avoids eye contact with fellow passengers, lives alone in a sleek Manhattan apartment and is surprised to find he has forgotten how to hug his nearest and dearest properly.

But a dramatic laying bare isn’t what the play achieves; it’s more of a gentle unpeeling, in that beguiling way Stephens has as a storyteller, but without the stinging blow he landed in his 30-minute monologue Sea Wall. This is a longer piece (80 minutes), but it feels slighter and more oblique, though both are studies in grief. Willem isn’t even addressing the audience in a wholly direct way: most of the time he is reading us the letters he wrote from the Lloyd Hotel in Amsterdam to his younger brother Pauli during a recent visit for a family funeral. The hotel room was his preference over staying at his family home. The funeral was Pauli’s, dead from a heart attack caused by an undiagnosed underlying condition.

Over the next few days, Willem transfers his thoughts about his experiences in Amsterdam to these sheets of hotel stationery: seeing his parents again after more than a decade’s absence, attending the funeral, spending time with his sister and her two young children, meeting up with his ex, picking up a Brazilian in a gay bar.

Young gives Willem a camp sweetness, with a creditable acquired American accent. He seems a tad too fey to be a tough hedgie who buys and sells whole cities, though there is a crisp side to him too. We follow the emotional responses he has recorded, which include him suddenly crying and burying his head in his Brazilian pickup’s chest. But he is still unused to kissing his family, he admits, bumping noses with his sister.

Young gives Willem a camp sweetness, with a creditable acquired American accent. He seems a tad too fey to be a tough hedgie who buys and sells whole cities, though there is a crisp side to him too. We follow the emotional responses he has recorded, which include him suddenly crying and burying his head in his Brazilian pickup’s chest. But he is still unused to kissing his family, he admits, bumping noses with his sister.

There are images swirling under the surface of Stephens’s writing here that you hope are going to surface more, though mostly don’t. One that sort of lands is the linking of old Amsterdam with New Amsterdam (aka New York), both places people went to to be enterprising and adventurous. Willem’s New York life is as blank as his mushroom-coloured apartment, with its minimal furnishings. He has nice breakfasts out, but there is no mention of friends. By contrast, the cityscape Willem describes as he walks along the Herengracht at night is one of big curtain-less windows, which he interprets as a message from the Amsterdammers to all the tourists: look how civilised and tolerant we are, we don’t shut you out, you can see right in. Is Willem opening up too?

There is a creeping political edge to his musings at times. He scorns the marginalising of Amsterdam’s ethnic minorities, pushed into outer districts, and fears for his little niece’s future, when the money and water and oxygen run out. “The world is done,” he concludes. Pauli’s more thoughtful but ultimately nihilistic approach to life begins to preoccupy him as well, the idea that life is a miserable train ride and there may not be a happy arrival to look forward to.

There is an appropriate blankness to Young’s Willem, who suddenly surprises by erupting with anger at one point over how much Pauli has upset the family by dying, but is otherwise pitched somewhere between impish and melancholy. His sister urges him to stay as she drops him at the airport for the flight back, but you sense he is nowhere near ready for that kind of commitment. He has managed to spend a (sleepless) night in Pauli’s room; to connect with his young niece; to meet his ex, Isaac, and see that Isaac, now a canal boat restorer, has no need of him.

Significantly he has started to piece together a song he heard in a bar (written by Mark Eitzel), which Young sings lines from here and there, a sad song that urges, “Go where the love is.” Finally, just before curtain down, he is able to sing the whole thing. It seems to signal a certain kind of breakthrough. But can Willem make up the emotional distance between him and where the love is? Is that even Amsterdam?

As the piece ends, you sense Willem has started to focus on himself, his excessive drinking, his emotional emptiness. For now, though, he is monitoring his breathing, checking and rechecking his flight documents, as if he’s trying not to disappear. These are slim pickings. Young is good company, sweet-voiced and affable, but you are left craving something more gutsy and raw.

Add comment