It was early in 1949. South Pacific, the follow-up to Rodgers and Hammerstein’s huge wartime hit Carousel, had entered the try-out phase before hitting New York. Late one night the production team were deep in one of those 11th-hour how-do-we-make-it-better meetings that always precede the launch of a new musical. Eventually the composer Richard Rodgers cut to the chase. “Fellas,” he said, “this show is perfect. Let’s go to bed.”

For all its perfection, for all the familiarity of “I’m Gonna Wash That Man Right Outta My Hair” and “There’s Nothin’ Like a Dame”, only a few flocking to South Pacific at the Barbican Theatre or on tour this autumn will know it. They may have caught the movie from 1956 that sold the darker elements of the story short. There are even those around who remember the original Broadway show, which transferred with its star Mary Martin to the West End in 1951. Among them are the Queen, who as Princess Elizabeth saw the show with her parents the night before she flew off to tour Australia, only to return as a monarch in mourning.

In her long reign, the last major production to bring South Pacific’s chrome yellow skies, stifling heat and smell of war to the London stage was Trevor Nunn’s revamp at the National Theatre. But until the Lincoln Center staged it in New York in 2008, there had not been a single major Broadway revival. Thanks to its daring but rapidly dating portrayal of race relations in a theatre of war, in America it was dismissed as “unrevivable”. That Lincoln Center revival is the show bound for the UK.

Watch the trailer for South Pacific filmed with the original Lincoln Center cast

South Pacific is that rarity, a musical about contemporary events. The book was taken from the loosely knotted stories of James A Michener’s Tales from the South Pacific (which, like the musical, won the Pulitzer Prize). It tells of Nellie Forbush, an Arkansas nurse stationed in the Pacific at a critical point in the Second World War when America, in the words of an officer, is “taking a pasting on two continents”. She falls for Emile de Becque, a French plantation owner 20 years her senior, only to reject him when she discovers that he has sired a pair of cuties by a Polynesian woman. Meanwhile, fresh-faced Lieutenant Joe Cable is smitten by a pretty young island girl who is practically pimped by her souvenir-selling mother Bloody Mary in the show’s most evocative song, “Bali Ha’i”. Cable’s Damascene valediction as he heads for combat is the song “You Have to be Carefully Taught”. It’s said that this daring homily about racism helped it to the Pulitzer, and got the Deep South in a lather when it toured there.

After its Broadway premiere, where it played for 1,925 performances, the show transferred to the West End in 1951. Its New York revival in 2008 restored one of the very greatest musicals to its rightful place in the popular imagination. Two of the stars of that production, Paulo Szot as Emile and Loretta Ables Sayre as Bloody Mary, remain. The other thing that has not changed is the creative team. Director Bartlett Sher (fresh from triumphantly staging Two Boys at the English National Opera), musical director Ted Sperling and musical stager Christopher Gattelli talk to theartsdesk about why South Pacific worked then and works now.

BARTLETT SHER, director

How did you come to be involved in this production of South Pacific?

How did you come to be involved in this production of South Pacific?

The Rodgers and Hammerstein Foundation were somewhat careful with the property because it was the last one that had never been revived on Broadway. It had had many weird productions. They had not found a director that they felt was good and I had recently produced The Light in the Piazza with Adam Guettel who happened to be Richard Rodgers’s grandson. The Lincoln Center had been asking to do a revival for a long time. I didn't listen to the music. I just read the script. I tend to think in musicals the book is the most important part and if the book is really solid you have a better chance of figuring out whether or not the thing is going to work. And the book was really great. There were a lot of parts of the book that had been interesting in the way they developed it. They had cut a lot of stuff that was also good and they were going to give me access to all of that. So there was a lot of interesting things to revisit in the script. Not to mention that it was four or five wars the US had been engaged in since: Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, Iraq. So our feelings of otherness, people of other cultures, was pretty profound at that point. I thought it was worth going back and looking at it again.

Was the musical completely unfamiliar to you? Had you seen the film?

I tried to watch both films but I didn’t get very far, not because I didn’t like them but because it was pretty clear early on that it wasn’t going to be helpful to watch the films. So I chose to look really at the script that Josh Logan had put together and go from there.

Rodgers and Hammerstein were well documented and archived. They had put together a script in 1948 which went into much greater detail about the racism issue at the time that was in their culture. They worked on that script out of town and then cut a lot of material as they came in. There was a lot of pressure on whether they should actually do “Carefully Taught”. The feeling was the story was too long. The Foundation gave me all of that information and I just went back through it and did a short workshop and put all of that stuff back in. When they were writing in the summer of 1948 there was the Democratic Convention, where the first platform on racism was introduced by Hubert Humphrey that was opposed by the southern Democrat Strom Thurmond. That conversation was very much broiling in postwar America. So it looks a little bit strange to us – why were they talking about race? - but when you researched it more carefully we found that it was a big part of the conversation of our culture.

Why do you think they latched onto the issue at this particular moment?

The show is a little bit about postwar optimism. It was similar in England. They threw out Churchill, put in Labour. Since they survived the great trauma there was this responsibility to make things better that took a different form in the US. We began to explore issues of race and economic equality. That was part of the culture of the time. Rodgers and Hammerstein were good Jews but they were always trying to look for ways to research and include more complex topics in musicals. Oklahoma! had the first death in a musical. They were enormously successful so they were pushing ahead.

Having such a daring source material for a stage musical, there was no way of knowing that it would work. Why in your opinion did it?

It is the most extraordinary adaptation of original material. If you read Michener’s stories, how those guys took those stories and distilled it is amazing. Musically it is as good as you can get. It has questionably the best group of songs you could ever imagine. Dramaturgically it’s very strong. It’s been criticised in the second act - the wireless scenes. For me it’s a little bit like working on the best of the Shakespeare. They are rich and reward you every turn you make with them. I think it’s in the history play vein. The remarkable political moment that still resonates in it is subtextually about who gets to be in our family. There is this great thing in theatre: torture the heroine. They did a smart thing by making Nellie the racist. Because it was Mary Martin, it was so shocking to see. To come to accepting these kids in her family and who could be at her dinner table was an extraordinary transformation politically and socially. It’s the only musical that is about real events and about what America is. And yet it doesn’t feel preachy or pushing anything. The issues for good or bad are still with us.

Mary Martin washes that man right outta her hair

And as for your restaging at the Lincoln Center, it was another great success for South Pacific. Given that it was often thought to be unrevivable, why did the revival work?

We were in the middle of an election. The debates, the conventions, all the stuff that was going on when they were writing it was happening: who gets to be in the family, who gets to be president, how do we engage overseas? The big question for America is otherness. The real issue is in the song “Bali Hai”. Taking a kid who was 18 and grew up in Iowa and put him in the South Seas and have him meet someone like Bloody Mary and engage in all these other cultures, that was just the beginning of America becoming aware of other cultures. That’s another thing that seems to resonate in it - because of Vietnam and now this engagement with the Muslim world. It continues to resonate in an American context. We are now reinvestigating the whole notion of right and left and the battles are more and more intense. South Pacific allows us to have an inclusive liberal message that both right and left agree on.

CHRISTOPHER GATTELLI, musical staging

Is there a reason why you are billed not as choreographer but for musical staging?

Originally when the show was put up Josh Logan did the choreography himself. The interesting thing to me was some of the performers in the show were actually in the war, they actually lived the show. So when they staged it I guess Logan said, “OK, let’s do everything that they did when they did it.” It was all down by him and the cast. They didn’t have a choreographer on the show. As the show kept being done I think people kept thinking of it in terms of musical staging. But to me it makes sense because when I went into my first meeting with Bart [Sher] he said, “My intention is to stage it as a play with music. These characters happen to sing.” That approach coupled with the actual material just works. My work on the show I hope complements his approach and it feels very natural and yet musicalised.

And yet the New York production is full of dance. How did you go about if not choreographing, then doing something very similar?

I had the incredible opportunity years ago of working with Doris Eaton Travis, an original Follies dancer who worked for Ziegfeld during the early part of the past century. She was 104 but still dancing. I tried to channel her energy and her physicality. There is a quality of that movement that I tried to get into the show. Dance nowadays is very clean and polished and almost very specific. Back in the day it was a lot looser and a little more free-form. I did a lot of research based on the style of the steps of that period. It felt very of that time and period.

How about the physicality of the soldiers?

For research purposes we brought in men from all forms of the military to show us how they walk, stand, salute, the basics of what it is to be part of the military and different branches of it. But the trickier part for me and what was hardest but the most fun and most rewarding was the Seabees, the guys who built the runways to the island. How do you physicalise men who pretty much lie around all day and then have to move? It was an interesting challenge. For that, too, I worked with a specialist in 1940s swing dancing. Back in the day everyone did it no matter what class. It was a huge part of the culture. I studied how the different classes would move with regard to the status. We had swing classes to get bodies used to that kind of movement. One of the hardest things about the show was getting dancers or performers to strip the clean technical style out of their bodies.

And then there is the Tonkinese dancing of Liat.

Bloody Mary would have originally come from China. As luck should have it our original Liat was proficient at classical Chinese dance so I did a fusion with what she knew but also what I studied. I tried to pay a little homage in “Happy Talk” to how they originally danced. There is a hand position in Chinese dance called the peacock which looks very similar to the original. We researched what Bloody Mary would have been exposed to and picked up and what she could have taught to her daughter.

TED SPERLING, musical director

This remarkable songbook had been silent in New York for 50 years. What did you discover about it when you started working on it?

I know that the Rodgers and Hammerstein organisation and Mary Rodgers and Alice Hammerstein were very protective of South Pacific in New York and felt it was the crown jewel of the canon. I had never seen a first-class production of it. I wasn’t sure initially how much I would like the show working on it. But having worked with Bart Sher before and the Lincoln Centre I knew this would be the best possible contemporary version. I knew the songs were amazing. It was more the show I was wondering about.

In retrospect, it clearly is a masterwork of integration of song and book, and underscoring the big revelation for us was how good the connective tissue was and how well thought through it was and how we could use it for staging and scenic design and acting. Josh Logan was a very big component of underscoring. His theory was that if the music told you a lot of what was going on inside the actor’s mind, the actor didn’t have to work as hard. There is a story about a disagreement with a moment in the underscoring when Cable tells Bloody Mary that he can’t marry Liat. The underscoring was a very crashing entrance for "Happy Talk" in a very minor and scary way. Robert Russell Bennett thought I was a little over the top so he orchestrated it very delicately for strings. Logan was furious and said, “That’s not what I want.” Bennett went back and orchestrated it for full orchestra but it was a breaking point and they never worked together again.

The consistency of good songs throughout is remarkable. There are very few shows of which you can say that. Guys and Dolls may be another. I love the simplicity of how the songs do their work. That was something I came to appreciate. Rodgers and Hammerstein are famous for using their songs to advance the plot but you realise in South Pacific it does it in a very subtle way while preserving the songs’ integrity as standards, which is quite a feat to pull off. “Some Enchanted Evening” has so much subtext but at the surface it’s just a very simple love song. It is really masterful.

The consistency of good songs throughout is remarkable. There are very few shows of which you can say that. Guys and Dolls may be another. I love the simplicity of how the songs do their work. That was something I came to appreciate. Rodgers and Hammerstein are famous for using their songs to advance the plot but you realise in South Pacific it does it in a very subtle way while preserving the songs’ integrity as standards, which is quite a feat to pull off. “Some Enchanted Evening” has so much subtext but at the surface it’s just a very simple love song. It is really masterful.

Do you have favourite songs in the show?

The one that in a weird way was most fun to conduct was “A Cock-Eyed Optimist”. I can’t really put my finger on why. It was just so pleasing. There was something simple and joyous and warm about that song. It’s very short and says what it wants to say. In our production we tried to layer in what it’s like to be in a war zone and to be an optimist in the face of all that. For Nellie to hang on to that is not so easy. That it will all work out despite the horrors that are possible is what makes it richer than a pure innocent song. She is no longer the girl she was.

Kelli O'Hara sings "A Cock-Eyed Optimist"

Bloody Mary takes part in two songs: “Bali Ha’i” and “Happy Talk”. How does Rodgers give expression to her?

One of the interesting things about Rodgers and Hammerstein is they wrote for these different locales. South Pacific has this South-East Asian slant to it for Bloody Mary’s songs but the orchestra is basically the same from show to show and the quality of those songs is created very subtly in the composition and the lyrics. There aren’t all these Balinese instruments and there’s no Vietnamese music. What we go for in our production is she is essentially a saleswoman and both songs are sales pitches. They are not just dreamy evocations of a place in time. They really have a very specific purpose.

“You Have to be Carefully Taught” had immense impact at the time. How do you get the most out of it?

Again it’s very short, says what it has to say and gets out of there. They don't dwell on it. It was certainly a dangerous song for their time and one they felt strongly about. We decided not to shy away from racism that they had softened a little bit between the original script and what they ended up with. And the way it’s staged in our production the African-American enlisted men are listening when it’s sung. I struggled with that song. My initial impulse was to do it very fast as a rant, an explosion. Over time I’ve returned more to the original recorded tempo. I feel like the song can’t be over too quickly. If Cable can be punishing himself in singing it then it has more power.

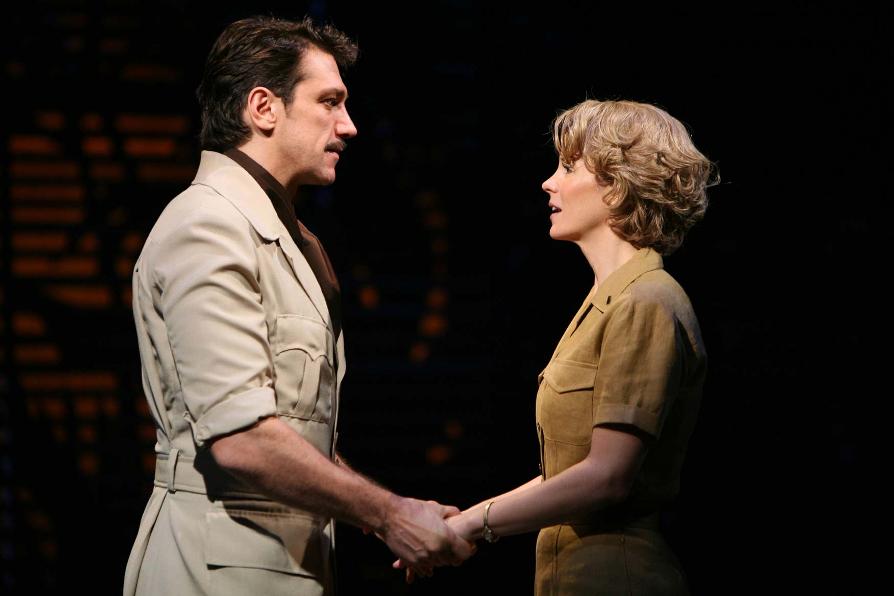

The part of Emile de Becque (Paulo Szot pictured with Kelli O'Hara) was originally written for a bass baritone. How does that impact on the casting?

The part of Emile de Becque (Paulo Szot pictured with Kelli O'Hara) was originally written for a bass baritone. How does that impact on the casting?

We took a very, very long time to cast Emile. We saw all the best music theatre baritones as well as seeing every opera singer we thought was possible. Bart having done so much work in opera was very sensitive to this issue. It just seemed no matter how good a theatre singer was there was still a difference between hearing a great theatre baritone and a great opera baritone. It just works best with somebody with that sound production. It’s very well designed: it’s only about 15 minutes of music. His moments have great impact. They are well timed and spaced.

There is a moment in the second act when everyone stops singing while Emile and Joe go on their top secret mission which we follow from the control room over the wireless. Is that a black mark against South Pacific as a musical?

Singing leaves the building for a while and that’s very unusual, but luckily underscoring saves the day. If you have very good actors in those parts those scenes can sustain and get us to the ending. It's the moment when the orchestra can pull out their books.

Add comment