How do you make Bernard Shaw sear the stage anew? You can trim the text, as the director Dominic Cooke has, bringing this prolix writer's 1893 play in under the two-hour mark, no interval. And you can introduce a non-speaking ensemble of women in period bloomers and the like as a silent commentary on the depredations indicated in the text.

Best of all, perhaps, is to cast as the brothel-keeper, Kitty Warren, and her Cambridge-educated scold of a daughter, Vivie, the actual mother-daughter pairing of Imelda Staunton and the stage legend's own daughter, the splendid Bessie Carter, who was seen to memorable effect last year in Dear Octopus at the National. (Caroline Quentin and her daughter, Rose, managed the same feat several years ago, so there's recent precedent for this casting gambit.)

The result is always keen-eyed and fascinating, as one has long come to expect from Cooke, whether this director is reinvigorating musicals like Follies (with Staunton, in fact) or landing Medea for contemporary audiences: Greek tragedy, he says in a prefatory note to the new published edition of Shaw's play, was in his mind, in fact, when staging Mrs. Warren. You're always aware of the clashing philosophical cymbals that underscore a text whose candour about the immorality that is part and parcel of a successful life has resonances, heaven knows, to today.

The result is always keen-eyed and fascinating, as one has long come to expect from Cooke, whether this director is reinvigorating musicals like Follies (with Staunton, in fact) or landing Medea for contemporary audiences: Greek tragedy, he says in a prefatory note to the new published edition of Shaw's play, was in his mind, in fact, when staging Mrs. Warren. You're always aware of the clashing philosophical cymbals that underscore a text whose candour about the immorality that is part and parcel of a successful life has resonances, heaven knows, to today.

The potential downside is the feeling on occasion that one is watching a provocative essay on the play, rather than the play itself: shortened Shaw seems as self-contradictory as the decision taken many years ago by the late Jonathan Miller to speed his way through Long Day's Journey Into Night. Characters have scarcely been introduced before they are seen to occupy points on a shifting moral spectrum, and one sometimes feels that an inevitable focus on the play's two women comes at the expense of the supporting cast - with one scorching exception.

There's no doubt that Bridgerton alum Carter, an incipient Nancy Mitford in the series Outrageous onscreen, comes naturally to the part: we take her "on her own merits", lineage notwithstanding, just as Sid Sagar's sweet-seeming artist, Mr Praed, says we should of Vivie early on. An avowed intellectual with a keen head for maths, she barely seems to know the determined woman who bustles into view, batting away any suggestion that her little "Vivums" (as it happens, Carter towers over Staunton) should be treated with respect.

The heart of the play are the two scenes that lock these two ladies in combat, one a modern-era new woman with a strongly unyielding sense of propriety, the other a redoubtable person with a past (that's to say, a prostitute-turned-proprietor) whose business acumen within a wayward (to many) choice of profession has allowed her the sort of seasoning in life you don't get from books. It's touching to see Staunton's eyes well with tears as her Kitty says to Vivie, "I brought you up well, didn't I, dearie?" - the play's onstage and offstage worlds melding into one. Later, asking "who is to care for me when I am old", Kitty poses a question shared out among many a family, onstage and off.

The heart of the play are the two scenes that lock these two ladies in combat, one a modern-era new woman with a strongly unyielding sense of propriety, the other a redoubtable person with a past (that's to say, a prostitute-turned-proprietor) whose business acumen within a wayward (to many) choice of profession has allowed her the sort of seasoning in life you don't get from books. It's touching to see Staunton's eyes well with tears as her Kitty says to Vivie, "I brought you up well, didn't I, dearie?" - the play's onstage and offstage worlds melding into one. Later, asking "who is to care for me when I am old", Kitty poses a question shared out among many a family, onstage and off.

Mrs Warren's refusal "to be a worn-out old drudge" clearly finds added cachet in a play whose casting sees a child following in her own parent's storied footsteps. It might be nice if Kevin Doyle's Rev Gardner didn't seem quite so foolish in his bombast, whilst Reuben Joseph's money-minded Frank Gardner seems to be on the outside of the action looking in and will presumably get more at ease with the part as the run continues.

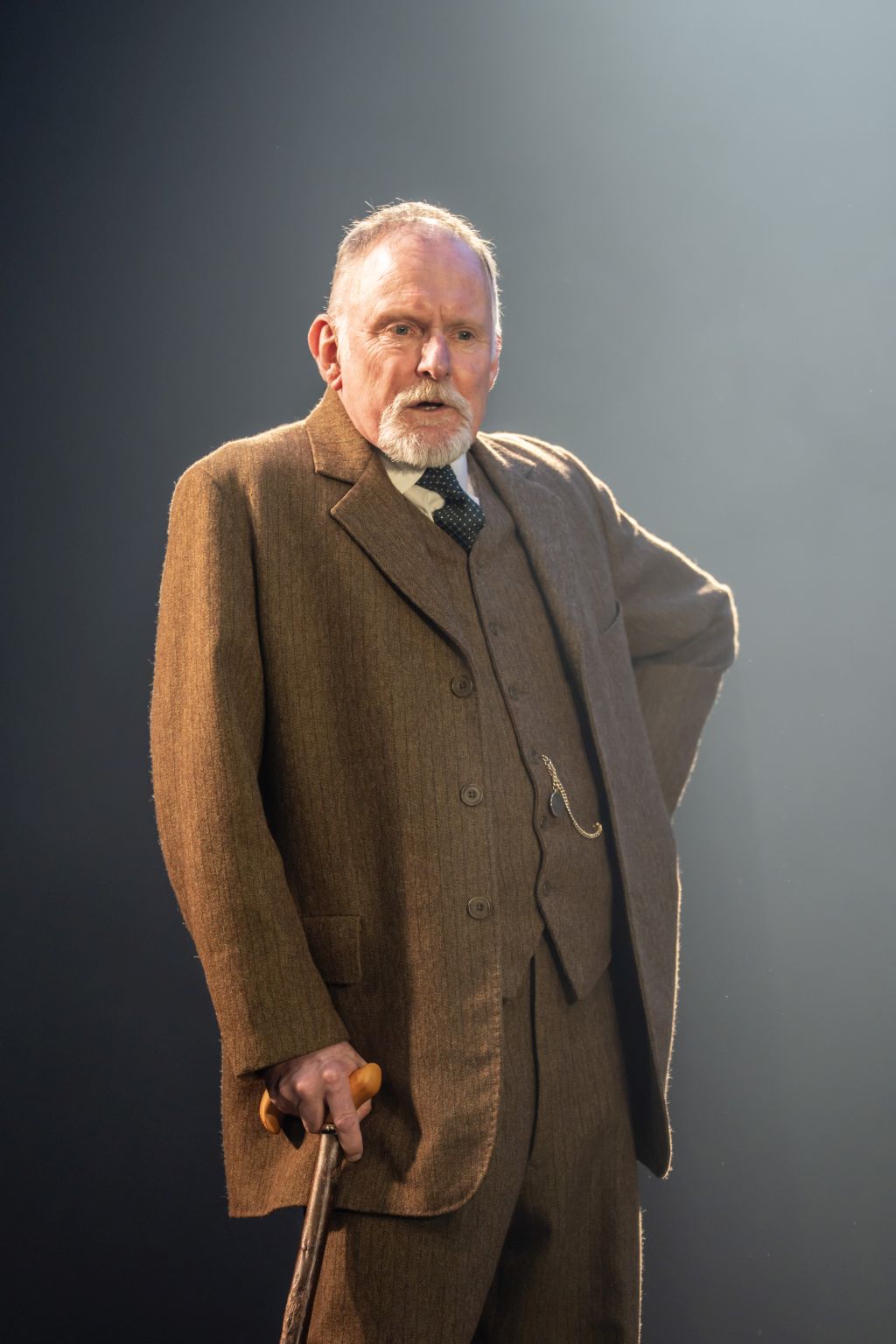

Commanding his own blistering sphere is the superb Robert Glenister (pictured left), whose business-minded George Croft long ago sacrificed morality on the altar of money to a degree one feels is all too common currency these days. Revealed as Kitty Warren's benefactor, Crofts has no time for life's piety and platitudes, just as Chloe Lamford's set moves symbolically from the lushly envisaged cottage garden of the opening scene to a clinical, antiseptic interior denuded of nature. The sense at play's end is of righteousnessness accompanied by austerity in a landscape laden throughout with hypocrisy. Morality talks; money, as ever, shouts.

- Mrs Warren's Profession till 16 August at the Garrick Theatre

- More theatre reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment