"How can we sleep for grief?", asks the brilliant and agitated Thomasina Coverly (the dazzling Isis Hainsworth) during the first act of Arcadia, a question that will come to haunt this magisterial play as it moves towards its simultaneously ravishing, and emotionally ravaging, end. Many of us asked ourselves that very question last November when the author died in the run-up to the Hampstead Theatre opening of Indian Ink, the play of his whose 1995 premiere followed Arcadia by two years.

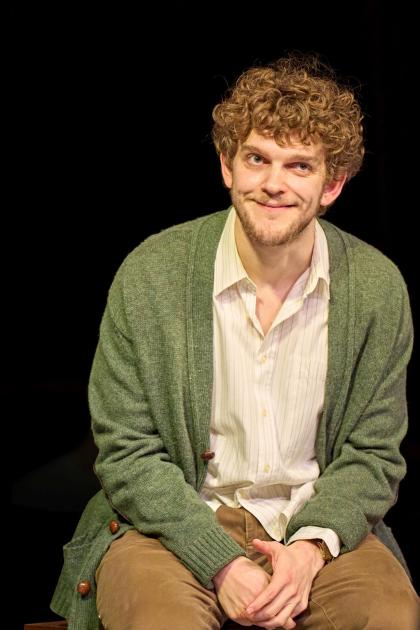

A sensible reply to the query is given by Thomasina's doting tutor, Septimus Hodge (the expert Seamus Dillane, pictured below), who suggests "counting our stock" as one way to safeguard the psyche against loss.

And so it is with the output of a writer whose death we mourn but who was at his absolute peak with a play that forms part of a breadth of work (make that "stock") which looks unlikely to be paralleled any time soon.

How lucky are we to be able to have these plays available for as long as people are keen to mine them. On that point, I doubt this particular text will soon find a staging to match the empathic reach of Carrie Cracknell's resplendent Old Vic revival, which manages the impossible, at least for me. Having been in attendance at Arcadia's world premiere at the National some 33 years ago come April, I had always thought I'd never see a staging to match Trevor Nunn's original, which boasted a cast to die for headed by Bill Nighy, Harriet Walter, Rufus Sewell, and Stoppard's longtime muse, Felicity Kendal.

Yet here the play is again, with at least three performers who eclipse all memory of their forbears. And even those who don't are superb in their own rights, the ensemble working in harmony to foreground feeling amidst the playfulness, fun and scientific and mathematical fodder that inform the text throughout. (Thomasina's hyper-attentiveness to a leaf makes you wonder where her restless mind might take her in our internet age.)

Reconfigured for an in-the-round staging that, at least from my stalls seat, allows for a revelatory intimacy, the writing ricochets this way and that, interweaving two distinct time periods until such point as they can't be "stirred apart" - to paraphrase the ever-observant Thomasina's awareness of the workings of jam atop rice pudding.

You become alert to details that illuminate larger themes rippling throughout - Thomasina looking skyward at the start as she will again, to wrenching effect, at the conclusion. Or the physical ease felt between her modern-day descendent, the scarcely less brilliant Valentine (the excellent Angus Cooper, pictured below), a Cambridge post-grad, and his mute brother Gus (William Lawlor), who has given up on the one thing everyone arounds him holds dear - speech.

Cracknell, too, understands what the best Stoppard productions always have. For all that this writer was punchdrunk on the possibilities of language - here, for instance, setting "Newtonian" against "Etonian" whilst also proffering a potted history in landscape gardening - he equally knows the value of stillness and silence: those moments when verbal byplay leave off and, in Arcadia anyway, we are allowed the opportunity to dance. Or to fall in love, however fully "carnal embrace" (the play's opening image) may in fact lead to ruinous, head-spinning loss.

And so it is that the play's early scenes, set in 1809 in a Derbyshire stately home known as Sidley Park, set an often-hilarious account of verbal jousting and literary oneupmanship against the burgeoning rapport - an impossible attraction, given their ages - of the precocious Thomasina, not yet 14, and her Cambridge-educated tutor Septimus, 22, who knows one thing for certain: that the young child-woman in his educational care is in fact smarter than he is, her boundless curiosity reverberating ineluctably, as does the play itself, between head and heart.

Whilst the grounds become fertile territory for erotic escapades in the gazebo and sightings of (an unseen) Lord Byron, the same locale in the modern-day is given over to the scarcely less competitive world of biography and academe. Given pride of place are two writers, Hannah (Leila Farzad) and Bernard (a jubilant Prasanna Puwanarajah), seen trying to unpack the very events from a century before that we are shown for ourselves.

Reams have been written unthreading the complex weave of the play, as if Arcadia were essentially classroom fodder whose meaning required a masters thesis on it. I readily admit that some prior awareness of Capability Brown, Fermat's Last Theorem, and - wait for it - iterated algorithms won't go amiss as you navigate the entirely riveting three hours on view.

But one masterstroke of the play is its ability to evidence in the writing the very topics it presents. Chaos theory is ripe for discussion, as is what the supremely rational Hannah describes as "the decline from thinking to feeling".

But the arc of the writing is to conjoin those two states of being, much as Alex Eales's elegantly geometrical set gives us dual revolves spinning in contrary directions. Overhead beams of light allow height to capture the eye in much the same way that depth of perspective did the first time round within a proscenium arch. (The expert lighting designer this time round is Guy Hoare.) Chaos theory may itself seem an abstraction until we consider it in relation to the Sidley Park hermit, who sequesters himself away on the grounds only to go mad with scribbling before dying a premature death.

That person's identity provides the abiding mystery of the play that at times seems like a upscale, decidedly bawdy version of Cluedo, not least in the 1809 sections which are largely devoted to figuring out who shagged whom - and when and where. But that's to sell short the shimmering affections that brew between Thomasina and Septimus or are voiced in the present-day scenes by the adoring Valentine, who is in every way (except one) Thomasina's natural inheritor.

Comedy abounds in the badinage that informs both time periods. Fiona Button's luscious Lady Croom may have about her a Wildean wit, but she's equally adept at pinpointing "the defect in God's humour" in His ability to misdirect the heart. Hannah and Bernard spar like some sort of embryonic Benedict and Beatrice, and there's more than a suggestion of Shakespeare's wounded heroine in Hannah's reluctance to dance - a lack of confidence that is never explored and to which Farzad lends a quiet eloquence. (The part is the play's most opaque, which seems odd given that it was written for its author's then-lover.)

One could go on, though in some ways the best option is simply to surrender to the play itself, as here served up with a tenderness that enfolds the cast within a cats cradle of affection: them for the play and also for one another. All the company are first-rate, but one has to single out Dillane - his father Stephen, a Tony-winning Stoppard veteran, among the press night audience - who brings to Septimus a fabulous robustness that makes the cruelty of this character's eventual reality doubly hard to bear.

And there simply is no praise too great for Hainsworth (pictured above) in the daunting role of the child-woman Thomasina, a Jamesian heroine if ever there was one who quivers at every moment with an avid appetite and excitement for the possibilities of life. (By play's end, she is on the cusp of turning 17, the part spanning the teenage years in ways that are not easy for a performer to accomplish.) Thomasina "must waltz", we are told near the end, and so we see Septimus giddily lifting her aloft, which is where Arcadia's audiences, by my reckoning anyway, are likely to find themselves.

- Arcadia at the Old Vic to March 21

- More theatre reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment