It’s a Wonderful Life, English National Opera review - Capra’s sharp-edged sentiment smothered in endless schmaltz | reviews, news & interviews

It’s a Wonderful Life, English National Opera review - Capra’s sharp-edged sentiment smothered in endless schmaltz

It’s a Wonderful Life, English National Opera review - Capra’s sharp-edged sentiment smothered in endless schmaltz

A committed company show, but Jake Heggie’s operatic musical is irredeemably shallow

Looking for a sparkly operatic musical, well sung and played, slick and saturated in a range of mainstream styles that stop short in the year the movie masterpiece It’s a Wonderful Life was released, 1946? Then Jake Heggie’s 2016 confection may be for you. One thing’s for sure, though: it may be trying to do something different from the Capra classic, and it’s welcome to have the Bailey family as African Americans, but this isn't a patch on the rather more layered film.

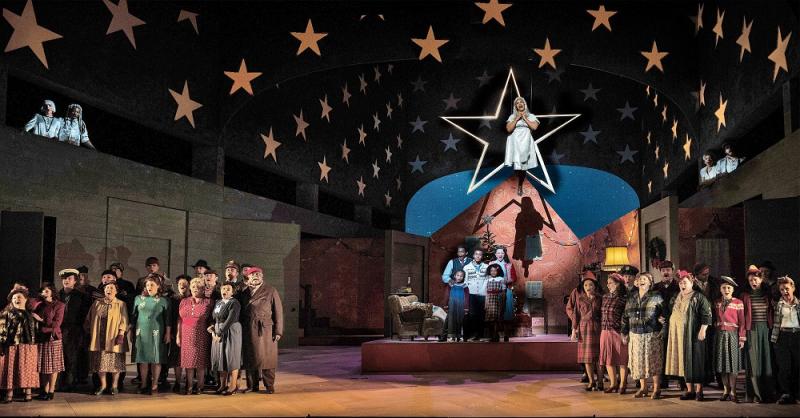

Endemic of the problem is that Capra’s crumpled, blue-eyed angel hoping to gain wings from helping a human in trouble has changed from old Clarence to young Clara, a twinkly soprano so empathetic that she soon gives you indigestion, as does the score. Danielle de Niese struts her stuff like the stage animal she is, but Clara’s decision to show nice but frustrated George Bailey, shackled to doing good in Bedford Falls, what life might be like if he'd never been born gives us a sudden chilly change of character way too late. Capra’s vision of Potterville, a place void of decent human endeavour, is one of the most memorable things about the film, but all we get is a sudden crunch to spoken dialogue whizzing through the consequences of what George’s total absence would mean to his own town in the penultimate of 21 scenes.  It's a real stumbling block in a score which has moved professionally if gooily through mostly cheery pastiche, favouring the saccharine at the expense of the grit (come on, George is seriously contemplating suicide when Clara is sent to save him - pictured above). It’s also not a good stretch for Frederick Ballentine, ardent tenor but not the most charismatic of actors; despite amplification, his spoken words are nearly all inaudible here. Emotional truthfulness is left to the superb Jennifer France as his great love Mary Hatch, managing to move us at the end of Act One (pictured below with Ballentine) in love music which hasn’t really been earned. I’d still give the entire score for “Buffalo gals, won’t you come out tonight?”, moonshine charm in the film’s most romantic scene between James Stewart and Donna Reed.

It's a real stumbling block in a score which has moved professionally if gooily through mostly cheery pastiche, favouring the saccharine at the expense of the grit (come on, George is seriously contemplating suicide when Clara is sent to save him - pictured above). It’s also not a good stretch for Frederick Ballentine, ardent tenor but not the most charismatic of actors; despite amplification, his spoken words are nearly all inaudible here. Emotional truthfulness is left to the superb Jennifer France as his great love Mary Hatch, managing to move us at the end of Act One (pictured below with Ballentine) in love music which hasn’t really been earned. I’d still give the entire score for “Buffalo gals, won’t you come out tonight?”, moonshine charm in the film’s most romantic scene between James Stewart and Donna Reed.

The opportunities for the rest of the cast are without exception well served, with four of ENO’s Harewood Artists as a quartet of winged angels, and Ronald Samm makes a big vocal impact as Uncle Billy. Nicole Paiement conducts with a fine sense of how the lyricism is intermoven with period dance music, and the ENO Orchestra glitters, though the textures could afford to thin more often. Gene Scheer’s patchy libretto is intelligible but rarely felicitously inflected; you feel Heggie is more interested in writing for instruments than voice.  Once we’re past the stardust visuals of the Prologue, Giles Cadle’s set feels as if it was done on the cheap, and Aletta Collins’ direction doesn’t make best use of the singing actors’ physical possibilities. The apotheosis is just hideous, lacking wings in a schmaltzfest that goes way beyond the worst endings of Strauss (Die Frau ohne Schatten and Die Aegyptische Helena).

Once we’re past the stardust visuals of the Prologue, Giles Cadle’s set feels as if it was done on the cheap, and Aletta Collins’ direction doesn’t make best use of the singing actors’ physical possibilities. The apotheosis is just hideous, lacking wings in a schmaltzfest that goes way beyond the worst endings of Strauss (Die Frau ohne Schatten and Die Aegyptische Helena).

France apart, there was more authenticity in the way ENO's resident spoken word artist Kieron Rennie celebrated daily kindnesses before curtain up than in the whole show. And I applaud Annilese Miskimmon, curiously absent during the recent crisis, for speaking so eloquently about Arts Council England's brutal cuts (did you know it’s a 30 per cent reduction for opera in England across the board?). Happy if this brings in different punters and sells well, but while not every opera has to be the bread of life, it's best to avoid too much Christmas pudding. The stars are for the enterprise, not the work.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Add comment