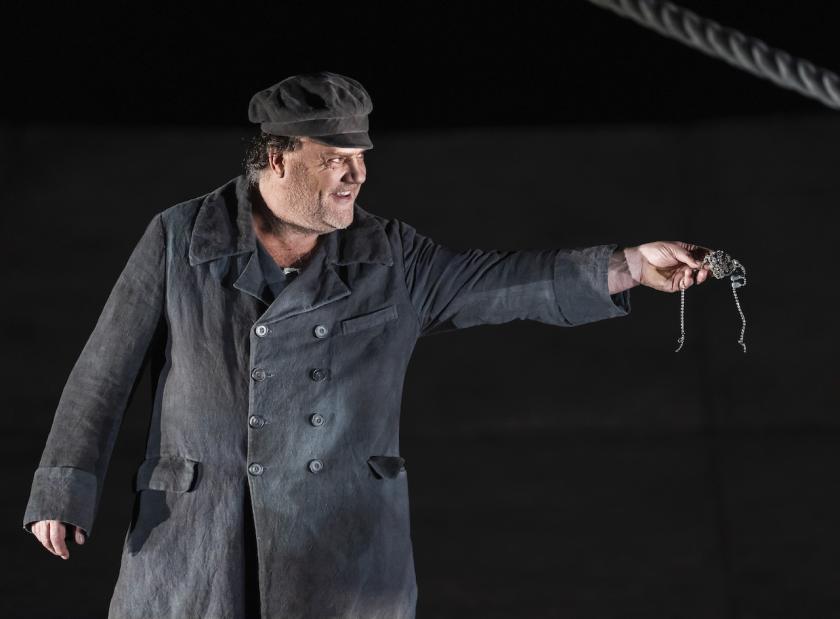

The shadow of Nosferatu hangs heavily over Tim Albery’s powerfully austere staging of Wagner’s opera of desire and damnation, which returns to the Royal Opera House 15 years after it premiered there. Bryn Terfel’s Dutchman is a subtly vampiric figure with his grey clothes and pallid face – an escapee from an Expressionist film hollowed out by his spiritual torment.

David Finn’s ravishing lighting design delivers some spine-tingling coups de theatre, whether it’s when looming shadow swallows Miles Mykkanen’s lone steersman lying on the stage, or when light on water creates ripple effects on the ROH’s duck-egg blue ceiling. Mike Levine’s stark, steeply raked stage design immerses us in the prow of Captain Daland’s ship as it struggles to dock during a storm. Though the crew, lit from the side as they haul frantically on ropes, are in modern dress, they look – in contrast to the Dutchman – like figures from an Old Master.

Hungarian conductor Henrik Nánási manages to create the same clear lines of contrast in the music as we see on the stage, nicely navigating the line between despair and understated comedy. After the swirling elemental introduction of the horns for the famous overture, there’s a sense of profound stillness as the cor anglais delivers the resolutely serene leitmotif for the Dutchman’s lover, Senta (with its clear echoes of the opening of Schumann’s piano concerto). Then the strings usher in the hurricanes once more as tempestuous rain streams down the billowing black curtain at the front of the stage, splattering loudly onto what we eventually discover is a strip of water representing the sea. Stephen Milling plays the captain Daland with brusque authority, whether he’s chastising the steersman for falling asleep while he’s on duty or pacing the deck as he searches for signs that they are coming in safely to land. Yet in his words there’s already the sense that there are dimensions to this storm that go beyond mortal understanding, "Wer bauft auf Wind, bauft auf Satans Erbarmen" ("The wind puts you at the devil’s mercy"). The sense of mellifluous yearning in both his and the steersman’s expressions of longing for loved ones at home contrasts starkly with the sinister monotone of the Dutchman’s entry, "Die Frist ist um" (plangently translated in the surtitles as "It is time"). No mistake that it’s like the tolling of a bell as he hauls a rope behind him like Marley’s ghost dragging his chains.

Stephen Milling plays the captain Daland with brusque authority, whether he’s chastising the steersman for falling asleep while he’s on duty or pacing the deck as he searches for signs that they are coming in safely to land. Yet in his words there’s already the sense that there are dimensions to this storm that go beyond mortal understanding, "Wer bauft auf Wind, bauft auf Satans Erbarmen" ("The wind puts you at the devil’s mercy"). The sense of mellifluous yearning in both his and the steersman’s expressions of longing for loved ones at home contrasts starkly with the sinister monotone of the Dutchman’s entry, "Die Frist ist um" (plangently translated in the surtitles as "It is time"). No mistake that it’s like the tolling of a bell as he hauls a rope behind him like Marley’s ghost dragging his chains.

As Senta, Elisabet Strid (above) is both empathetic and empowered; though it’s her father, Daland, who’s greedily promised her to the Dutchman as the latter plies him with jewels, there’s no doubt that she’s intoxicated by the challenge of ending his torment. She first enters carrying an exquisite model of a five-sailed ship that she places in the shimmering water at the front of the stage. At this point she’s like an apparition of an idealised future as she paddles in the miniature sea while it glimmers rust red. But it turns inky black as she departs and the Dutchman laments the end of "undying fidelity".

This production is two hours and 20 minutes with no interval, yet the lucid storytelling and gripping central performances mean that it flies by as fast as a ship pursued by an infernal storm. The sense of otherworldly doom is nicely interspersed with flashes of visual wit – not least the moment when the clothing factory where Senta works descends onto the stage like a modernist spaceship: a symmetrical masterpiece of sewing machines and sardonic seamstresses.  Strid’s warm, resonant soprano carries effortlessly across the opera house, not least in Senta’s famous ballade about the Dutchman, in which she savours the spiky intervals at the same time as she sculpts out her character’s yearning. While her bravery shines through she also potently conveys the nightmarish aspect of Senta’s terror as she stumbles onto her father’s ship and finds it full of desolate phantoms.

Strid’s warm, resonant soprano carries effortlessly across the opera house, not least in Senta’s famous ballade about the Dutchman, in which she savours the spiky intervals at the same time as she sculpts out her character’s yearning. While her bravery shines through she also potently conveys the nightmarish aspect of Senta’s terror as she stumbles onto her father’s ship and finds it full of desolate phantoms.

Yet it’s Terfel who’s the quaking heart of this production, as he simultaneously expresses the Dutchman’s otherworldly anguish and the pain intertwined with his yearning for a better future. Even at the apparently happy moment when he and Senta are betrothed there’s a sense of the doom he feels. The quiet intensity of the passion in his voice briefly elevates to incredulous rapture before the torment engulfs him once more. Stooped and wretched, he conveys both centuries of agony and the pathos of the dream that yet again has failed to set him free.

Add comment