First Person: Marc Burrows on getting to know Sir Terry Pratchett | reviews, news & interviews

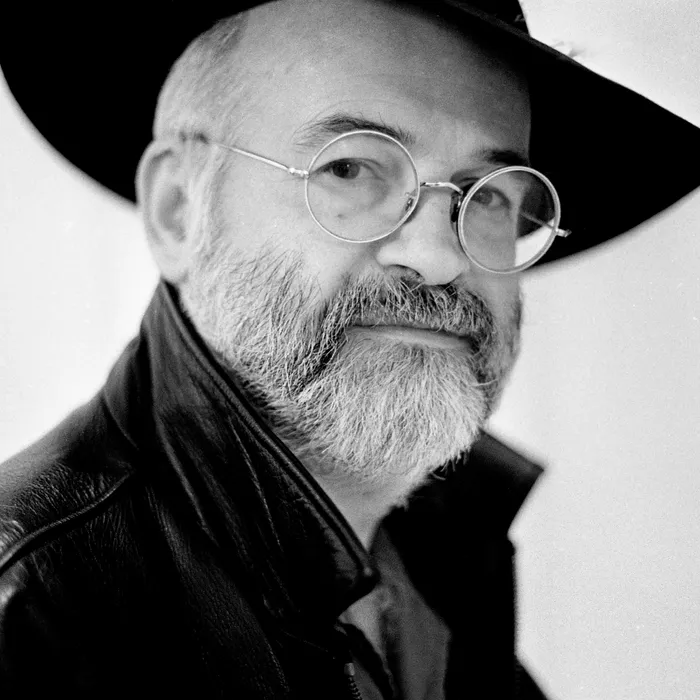

First Person: Marc Burrows on getting to know Sir Terry Pratchett

First Person: Marc Burrows on getting to know Sir Terry Pratchett

In the lead up to his live lecture on the life of Terry Pratchett, biographer Marc Burrows discusses the lessons he’s learned from Discworld and beyond.

In a very real sense, Terry Pratchett taught me how to write. I first came across his work when I was 12 years old, in the early 90s.

My parents had been given copies of two of the earliest books in his Discworld series, Guards! Guards! and The Colour of Magic, by a bloke down the pub – which is how you’re supposed to get Discworld books – and, knowing that I was an utter nerd with a preposterously overactive imagination and a love of silly humour, passed them down to me.

I loved them from the word go, and not just because there’s (unusually for Pratchett) swearing in the opening pages of both books, which is something I'd certainly not found in my Roald Dahls and Enid Blytons. What I found was the secret language of references. The idea that you can nod to something, a film, a song, another book, and create a little private joke between yourself and the reader. A moment that was just for you. I also learned that I wasn’t the only one who’d noticed that the universe is weird and baffling and perpetually unfair. Rincewind the wizard, the “hero” of The Colour of Magic, the first Discworld book, had noticed it, too. He’d practically built his personality around dealing with this fact. And Rincewind knew it because Terry Pratchett knew it.

Terry, a former journalist who at the time of writing the book was working as a press officer for the electricity board, knew about the frustration of petty bureaucracy, the death-by-a-thousand-cuts of little injustices that plagued modern life, the fundamental wrongness of a world that refused to do the right thing and operate like a story says it should. I’d always felt like that. I’d never known you could write books about it. I didn’t know you could make them funny. I didn’t know you could throw dragons in, too. Reading Pratchett was a sharp lesson in how a worldview can be pushed through a bunch of nerdy in-jokes, wrapped around solid storytelling and real characters in unreal situations, and delivered to the heart via the sense of humour. And that was just book one. And it’s the worst one in the series.

That became evident when I dug into Guards! Guards!, the other book gifted to my parents by that unknown diamond of a human down the pub. Guards! Guards! was written six years after 1983’s Colour of Magic; six years that Pratchett had spent honing his craft. Terry’s first book, a fairly light children’s fantasy called The Carpet People, had been published in 1971 when he was just 24. Two sci-fi novels followed: 1975’s The Dark Side of the Sun and 1981’s Strata, with the first Discworld, The Colour of Magic, appearing in 1983 and its sequel, The Light Fantastic, coming in 1986. Five novels in 15 years. Not bad. Just four years later, he’d doubled it. Equal Rites and Mort followed in 1987, Sourcery and Wyrd Sisters in 1988 and Pyramids and Guards! Guards! as well as a new children’s book, Truckers, in 1989. He would publish at least two novels a year, more often than not, for the rest of his life. In 1990 he managed five. That’s another thing I learned from Terry: put the work in. Guards! Guards! is exponentially more sophisticated than Colour of Magic, and contains another brilliant writing lesson that Pratchett deploys throughout his career – playing with our expectations. The hero is supposed to be a hunky, good natured young man called Carrot; another naive youth whom the plot could happen to, a trick he’d used already in Mort and Pyramids. Carrot is a classic fantasy archetype: the innocent young man with a mysterious destiny. He has an ancient sword and a crown-shaped birthmark, and was raised by Dwarfs after his family was killed by bandits when he was a baby. He basically has “lost heir to the throne” scrawled across his entire life. We know this story. We know how it will go. Destiny is at play. And then… it just doesn’t happen. Pratchett diverts the plot. Carrot joins the City Guard, captained by the real “hero” of the tale, an alcoholic cynic called Sam Vimes. Just as Rincewind was Pratchett’s bafflement and fatalism, Vimes was his anger. He’s a character that seethes at injustice, self-loathing and frustration at his own powerlessness. Other men have chips on their shoulder – Vimes has a chip supper, complete with a battered sausage, a bread roll and a can of drink. He’s an upturned plug on the bedroom carpet of destiny. We think the story is going one way, and then suddenly we’re howling, clutching our foot, and nothing is going to plan anymore. It’s a bait and switch – the naive boy with the hand of destiny on his shoulder stays in the supporting cast, and the bitter, middle-aged cynic with the grudge comes to the fore. It’s a masterclass as a writer – direct the audience one way, play into their expectations and then completely confound them. When I started doing stand-up comedy, that was a hugely important lesson. Let the expectations of the story do the work for you. It’s like a magic trick.

Guards! Guards! is exponentially more sophisticated than Colour of Magic, and contains another brilliant writing lesson that Pratchett deploys throughout his career – playing with our expectations. The hero is supposed to be a hunky, good natured young man called Carrot; another naive youth whom the plot could happen to, a trick he’d used already in Mort and Pyramids. Carrot is a classic fantasy archetype: the innocent young man with a mysterious destiny. He has an ancient sword and a crown-shaped birthmark, and was raised by Dwarfs after his family was killed by bandits when he was a baby. He basically has “lost heir to the throne” scrawled across his entire life. We know this story. We know how it will go. Destiny is at play. And then… it just doesn’t happen. Pratchett diverts the plot. Carrot joins the City Guard, captained by the real “hero” of the tale, an alcoholic cynic called Sam Vimes. Just as Rincewind was Pratchett’s bafflement and fatalism, Vimes was his anger. He’s a character that seethes at injustice, self-loathing and frustration at his own powerlessness. Other men have chips on their shoulder – Vimes has a chip supper, complete with a battered sausage, a bread roll and a can of drink. He’s an upturned plug on the bedroom carpet of destiny. We think the story is going one way, and then suddenly we’re howling, clutching our foot, and nothing is going to plan anymore. It’s a bait and switch – the naive boy with the hand of destiny on his shoulder stays in the supporting cast, and the bitter, middle-aged cynic with the grudge comes to the fore. It’s a masterclass as a writer – direct the audience one way, play into their expectations and then completely confound them. When I started doing stand-up comedy, that was a hugely important lesson. Let the expectations of the story do the work for you. It’s like a magic trick.

It’s a lesson I’ve had to bear in mind as I’ve worked on my live lecture about Sir Terry’s life. I had written a biography of the great man that was published in 2020 – the first real biography anyone had ever written of him – and though that had been extraordinarily hard work, it was a relatively straightforward task. He was born in 1948 and died in 2015, and after that it’s just a matter of connecting the dots via research. You can’t really pull narrative tricks like the Guards! Guards! bait and switch in a biography. As a genre, it doesn’t lend itself to misdirection.

Then came the idea of developing a live show for the Edinburgh Fringe, and I realised very early on that I couldn’t simply retell the linear story of the book. There’s no way to fit the necessary detail into a show lasting less than an hour, and the structure felt formulaic. I needed to change tack. Which is the point I realised that Terry himself had given me the road map. Over 30 years of reading his books had taught me exactly how to talk about his life and make it funny and moving and keep people engaged. I realised I could hide little jokes and references that, just as he did, would provide tiny little pops of joy for those who picked up on them, while not distracting the people who didn’t. I could plant ideas at the start that paid off at the end, as Terry often did. I could direct the audience’s attention away with one hand, while pulling a sixpence out of their ear with the other.

It’s a privilege to tell his story, and one I don’t take lightly. Occasionally people ask me what I think Terry would make of it, and of course I can’t know. I hope he’d enjoy it. I’m pretty sure he’d be delighted that someone took his life’s work seriously enough to put it together in the first place. Honestly, though, what I’d really hope is that he could see how much the show was a tribute to him, not just thematically but in its structure and tone. Terry taught me to tell his story – to put my worldview into it, to develop a bond with the audience through in-jokes, to keep them on their toes with misdirection, and above all to work absurdly hard. I hope I’ve made him proud.

- The Magic of Terry Pratchett will be performed at 5.30pm in Gilded Balloon Teviot (Dining Room) from 2-28th August (not August 14)

And it wouldn’t be Terry Pratchett without footnotes, would it? Each performance will be followed by a separate interactive show, ‘The Magic of Terry Pratchett: The Footnotes’, featuring a Q&A, readings from rare Pratchett works and interviews with special guests, including friends and colleagues of Sir Terry and Discworld fans from across the Fringe and beyond.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Add comment