Hallenberg, Monteverdi Choir, English Baroque Soloists, Gardiner, BBC Proms review - a vindication of voices | reviews, news & interviews

Hallenberg, Monteverdi Choir, English Baroque Soloists, Gardiner, BBC Proms review - a vindication of voices

Hallenberg, Monteverdi Choir, English Baroque Soloists, Gardiner, BBC Proms review - a vindication of voices

Choral singing at its finest roars back to the Proms

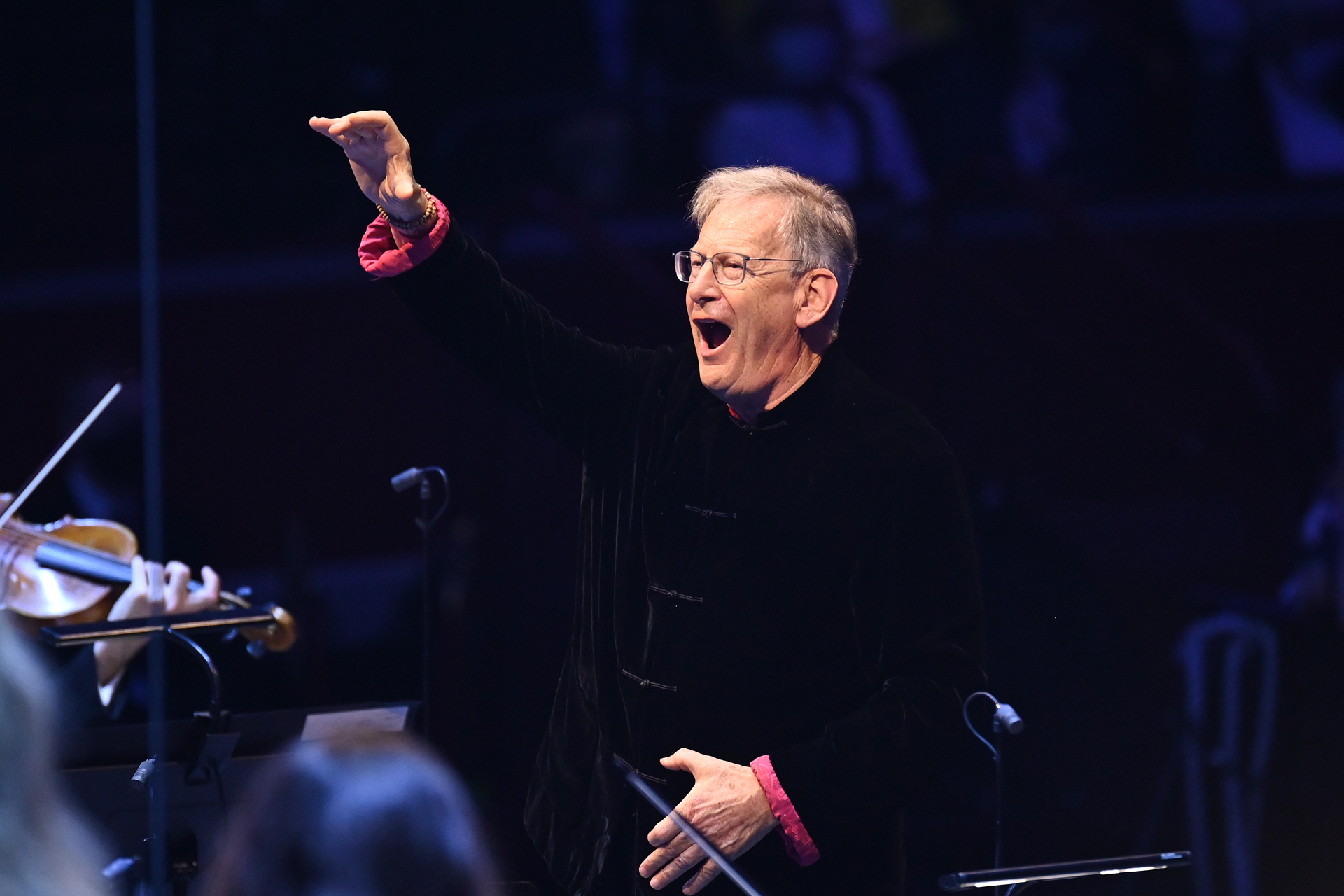

Choral singers have suffered more than most from erratic and irrational Covid prohibitions while riskier mass pursuits have gone ahead. So when one of the world’s great choirs returned to the Proms with the conductor who has guided them for over half a century, the sense of occasion was palpable.

It offered three Baroque masterworks written by two up-and-coming composers at or around the age of 22: Bach’s Easter cantata Christ lag in Todes Banden, sandwiched between Handel’s Donna, che in ciel and his mighty, astonishing Dixit Dominus. At this point, around 1707, Bach was proving his sober and sombre Lutheran credentials while, in Rome, Handel the chameleon experimented with Italianate, Catholic floridity. All three pieces, however, proved that musical genius arrives early and leaves an indelible stamp. Strands of the DNA that would later mould the Passions, or even Messiah, twisted through the evening.

Bach’s Christ lag in Todes banden, however, requires restraint, control and a sort of deeply glowing austerity. After the dark-hued sinfonia that opens it, these seven variations built around a Luther hymn intertwine arias for tenors, altos or sopranos (here, as groups rather than individuals) with sections for full chorus. The crisp attack of the Monteverdi singers’ entries, either in their separate knots or all together, gripped and moved, as did their knife-sharp clarity of diction and virtuosic back-and-forth handovers. Of course, Gardiner brings his own brand of rhythmic excitement to every corner of Baroque repertoire, but it’s not all unrelenting pace and bite. Unaccompanied (save for James Johnstone’s chamber organ), the chorus “Es war ein wunderlicher Krieg” had an almost glacial stillness and lucidity, followed by the heart-stopping mix of monumentality and tenderness in the basses’ aria “Hier its das rechte Osterlamm”. Bach’s scoring here has a granitic, modal, almost medieval quality – so different to Handel’s Roman high jinks – and the Monteverdis did ample justice to this brooding, impassioned asceticism.

The other soloists from this choir of stars excelled too: the alto Bethany Horak-Hallett, tenors Graham Neal and Peter Davoren, and Dingle Yandell’s bass. Gardiner, as always, plays a trump-filled hand packed with rhythmic and dynamic aces, and some breath-stopping ambushes engineered by this master of Baroque shock tactics. It takes discipline as much as power to prevent this love of drama from sounding merely spectacular rather than soulful: both the Monteverdi singers and their players have that virtue in abundance. The show-stopping final “Gloria”, with its choral leaps and runs, swaggers into the future where Messiah and other marvels wait. For the adoring audience, young Bach and Handel, in Gardiner’s hands, set a seal on the choral comeback with a triumphal vindication of the human voice. We wanted more, and we got it, in two encores that reprised passages from Dixit Dominus with all the ferocity, and sensitivity, we enjoyed first time round. Gardiner’s 60th Prom crackled with youthful energy – and stamina.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Add comment