Classical CDs Weekly: Brahms, Philip Sawyers, Ligeti Quartet | reviews, news & interviews

Classical CDs Weekly: Brahms, Philip Sawyers, Ligeti Quartet

Classical CDs Weekly: Brahms, Philip Sawyers, Ligeti Quartet

Romantic chamber music, a contemporary symphony and magical sounds from a young string quartet

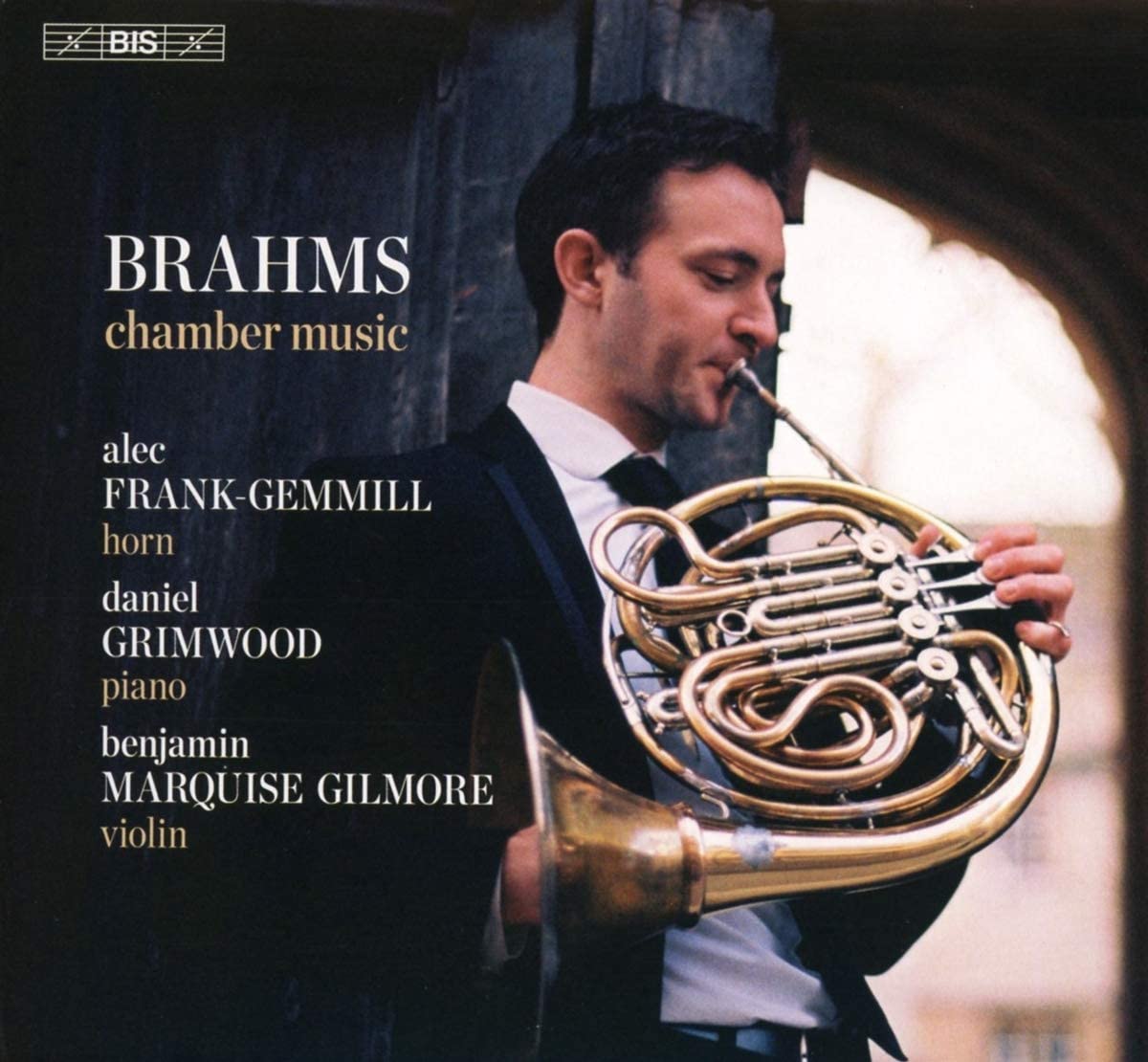

Brahms: Chamber Music Alec Frank-Gemmill (horn), Daniel Grimwood (piano), Benjamin Marquise Gilmore (violin) (BIS)

Brahms: Chamber Music Alec Frank-Gemmill (horn), Daniel Grimwood (piano), Benjamin Marquise Gilmore (violin) (BIS)

An hour’s worth of Brahms’s chamber music for horn? Almost; we get the familiar Opus 40 Trio here, plus arrangements of the Op 38 Cello Sonata and the Scherzo in C minor. Horn player Alec Frank-Gemmill makes the point that substituting different instruments in chamber music was common practice in the mid-19th century. Simon Smith’s transcription of the C Minor Scherzo is a giddy romp, taking its cue from the music’s 6/8 hunting rhythms, the horn part’s huge leaps made more manageable on a Paxman triple horn. The Cello Sonata has been transposed up a minor third to E minor, a better fit for the modern instrument’s compass. The lower cello writing rarely sounds like an authentic Brahmsian horn part, but the transcription is wonderfully effective, especially when Frank-Gemmill’s glorious high register is unleashed. He’s nicely matched by pianist Daniel Grimwood, particularly in the terse fugal finale.

Violinist Benjamin Marquise Gilmore joins the pair for the Horn Trio. You’re immediately aware that the horn sound is softer, more focused, Frank-Gemmill switching to a narrow-bore instrument owned by Dennis Brain’s father Aubrey, who recorded the work with Adolf Busch and Rudolf Serkin in 1933. This work is frequently played on the natural (unvalved) horn; using a vintage instrument with piston valves allows Frank-Gemmill’s quieter playing to really sing. This is a gloriously soulful performance with the Adagio mesto packing a huge emotional charge. The close is so desolate you wonder how Brahms will pick himself up. He does, of course, with another galumphing 6/8 rondo, Frank-Gemmill’s agility all the more impressive for being played on a vintage peashooter.

Philip Sawyers: Symphony No. 4, Hommage to Kandinsky BBC National Orchestra of Wales/Kenneth Woods (Nimbus Alliance)

Philip Sawyers: Symphony No. 4, Hommage to Kandinsky BBC National Orchestra of Wales/Kenneth Woods (Nimbus Alliance)

Anyone needing proof that social media isn’t necessarily a bad thing could do worse than follow the World Cup of British & Irish 20/21C Symphonies (@britsymphcup) on Twitter. It’s been rumbling on for months and has introduced me and many others to swathes of works I’d never have encountered otherwise. A series of friendly playoffs, you might find Elgar 2 pitted against something by Humphrey Searle, with many of the lesser known works accessible via YouTube links. An incidental pleasure has been its reminder that good symphonies are still being written. Philip Sawyers’ superb 3rd Symphony was a contestant back in July, and here’s the first recording of his recently completed three-movement 4th, its layout in part due to Sawyers’ feeling that “by the time the third movement was complete, there was nothing more to say.” This is serious, intelligent music, brilliantly scored. Sawyers never plays to the gallery. He can be dissonant, making imaginative use of dodecaphony and punchy short motifs. He’s also got a gift for long-breathed melody; I’m thinking of the rhapsodic string writing four minutes into the piece, or the haunting first movement coda. Sawyers recycles much of the first movement’s material in a virtuosic, skittish scherzo, the spikiness tempered by a languorous middle section.

A long, lyrical Adagio finale wraps things up beautifully, Sawyers’ slow move to unabashed D major never forced. The final minutes are stunning. It’s fantastically performed here, Kenneth Woods’ BBC National Orchestra of Wales never sounding stretched, with the brass on stellar form. Woods’ coupling is Sawyers’ Hommage to Kandinsky, premiered in 2014. Woods’s sleeve notes suggest that the piece is as much a nod to Richard Strauss’s tone poems as it is to Kandinsky’s canvases. It’s an abstract study in colour and form rather than a musical depiction of specific artworks, its 28 minute span unfolding like a single movement symphony. Brilliantly orchestrated, it’s handsomely performed and recorded.

Ligeti Quartet – Songbooks Vol. 1 (Nonclassical)

Ligeti Quartet – Songbooks Vol. 1 (Nonclassical)

Most of this fascinating anthology is a collaboration between the Ligeti Quartet and composer Christian Mason. His two ‘songbooks’ here are based on different examples of throat singing, where the vocalist manipulates overtones to produce multiphonic effects. This CD demonstrates how overtones can be exploited on stringed instruments. Mason’s Tuvan Songbook is based on four numbers recorded in Central Asia, each propulsive dance making reference to the importance of the horse in Tuvan culture. Mason brilliantly assimilates the various ingredients: the quartet’s players reproduce the folk dance of “Kuda Yry”, singing along at several points. And then, a few minutes in, we’re treated to a startling, eerie display of harmonics and overtones. It’s enchanting, and these players never sound as if they’re going through the motions; the sense of intent is a constant.

The Sardinian Songbook is earthier, prompted by Mason’s discovery of the Tenores di Bitti as a student. These four numbers are earthier, and as with the Tuvan songs, it’s the moments where the overtones emerge which really take flight, as in the “Ballate a Ballu Tundu”. Listen carefully and you can hear the musicians standing further apart from each other as the work progresses, the sound becoming lighter and airier. Wonderful. The two collections are bookended by “Sai Ma”, Mason’s transcription of a horse-related number from China, originally performed on the two-stringed erhu, and Jacob Garchik’s arrangement of “Sivuniittinni”, a stark, powerful number composed by the Canadian Inuit singer Tanya Tagaq. You’ll be hooked, I promise, and a second volume is in preparation.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Add comment