Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer, Barbican Art Gallery review - mould-breaker, ground-shaker | reviews, news & interviews

Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer, Barbican Art Gallery review - mould-breaker, ground-shaker

Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer, Barbican Art Gallery review - mould-breaker, ground-shaker

A crash course in the life and times of an iconoclast and muse

It must be tough being Michael Clark, subject of one the largest retrospectives ever dedicated to a choreographer still living. Post-punk’s poster boy is that curious thing, a creative figurehead who defined a very particular anti-establishment strand in Britain’s recent history but who is virtually unknown to today’s under-40s. Michael who?

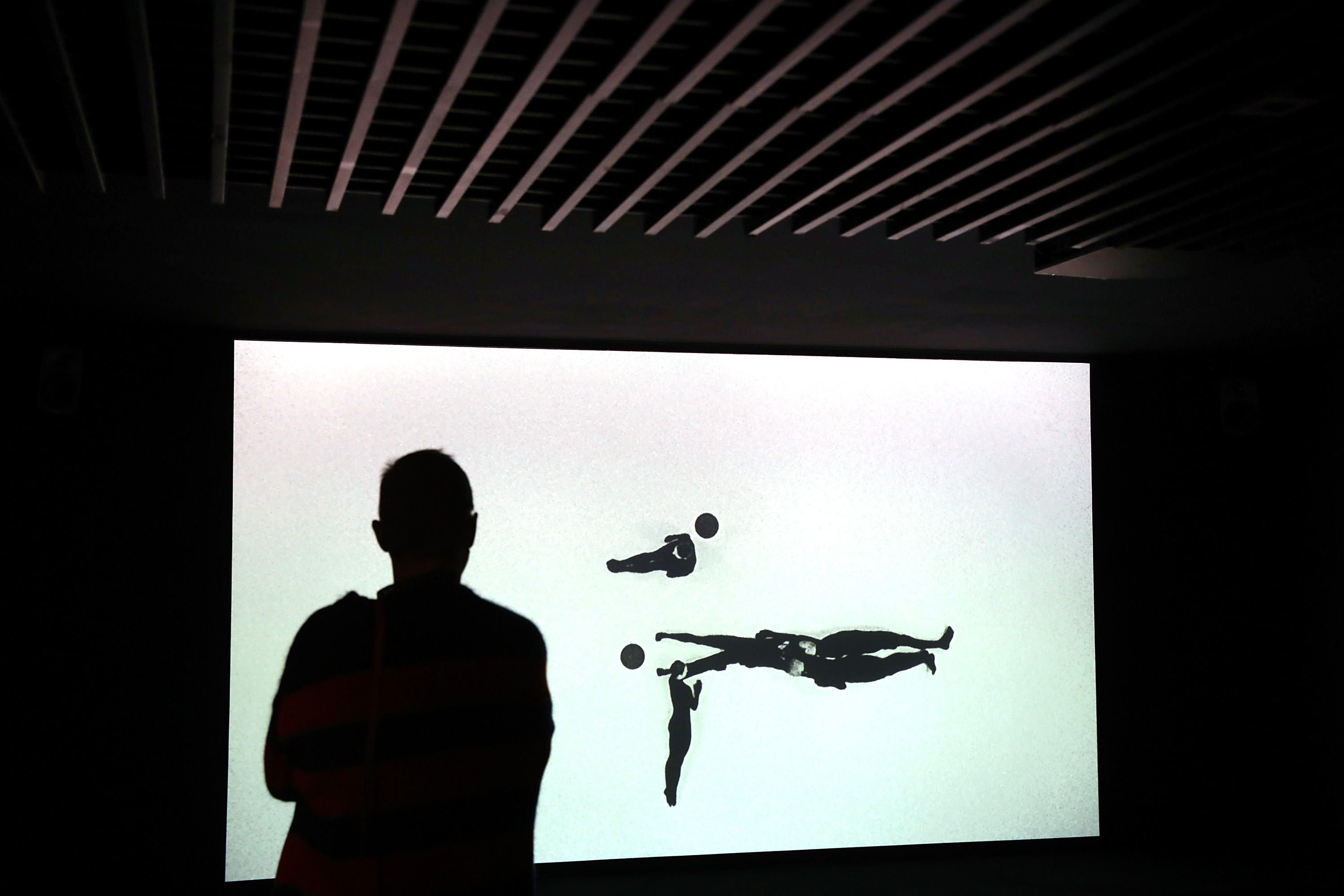

In many ways the Barbican Gallery is ideally suited to the task of presenting the full picture. The gallery’s absence of natural light works well for Charles Atlas’s film installation, a mashup of two films he made in the Eighties including Hail the New Puritan (1986), which shows the young Clark to be anything but. By the age of 22 the dancer had established his own company, and the extensive film offers an intriguing close-up of its members at work and play.

Some may be puzzled as to why Atlas’s film need be shown simultaneously on seven large screens on angled walls, but the blitzkrieg of light and sound is perhaps meant to evoke the sensual overload of the Eighties club scene. It was in nightclubs such as Heaven, and the notorious Taboo, where the performance artist Leigh Bowery was MC, that Clark forged many of the friendships that inspired his work. Two large walls of the exhibition are devoted to the costumes Bowery designed for him – not just the provocative stuff, but also sumptuous pieces such as gimp masks made from jewelled crewelwork, or fantastical things in feathers.

Less successful, in terms of the exhibition experience, is the extensive film archive accessed from a series of monitors into which visitors are invited to plug their own headphones. Everything is here, from a rare recording of Clark’s solo Soda Lake (1981), choreographed by Richard Alston for Ballet Rambert, to Clark’s most recent – and thrilling – choreography of his own, seen at the Barbican in 2016. To a simple, rock'n'roll ... song showed his skill at its most refined, as well as putting his musical taste in a nutshell. Together David Bowie, Erik Satie and Patti Smith made up his universe of sound.

Nothing wrong with the material, then. The frustration is not being able to select the clips you want to see. Each sequence being on a loop, I had to plough through 20 minutes of Peter Greenaway’s tediously overegged Prospero’s Books (in which Clark was counter-cast as Caliban) in order to access the three-minute gem behind it. This denial of choice is presumably a Covid precaution – many hands pressing buttons clearly would not do. But what it means is that, unless you plan to spend an entire day in the gloom of the Barbican Gallery, it’s impossible to see everything in the exhibition. I clocked up three hours and missed loads.

Ultimately, then, this is a show for affirmed Clark fans. And there are plenty enough of them, albeit all of a certain age.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment