Bach’s The Art of Fugue, Angela Hewitt, Wigmore Hall – the many voices of humanity | reviews, news & interviews

Bach’s The Art of Fugue, Angela Hewitt, Wigmore Hall – the many voices of humanity

Bach’s The Art of Fugue, Angela Hewitt, Wigmore Hall – the many voices of humanity

The Canadian pianist vindicates the master's last big collection in concert

How do they do it?

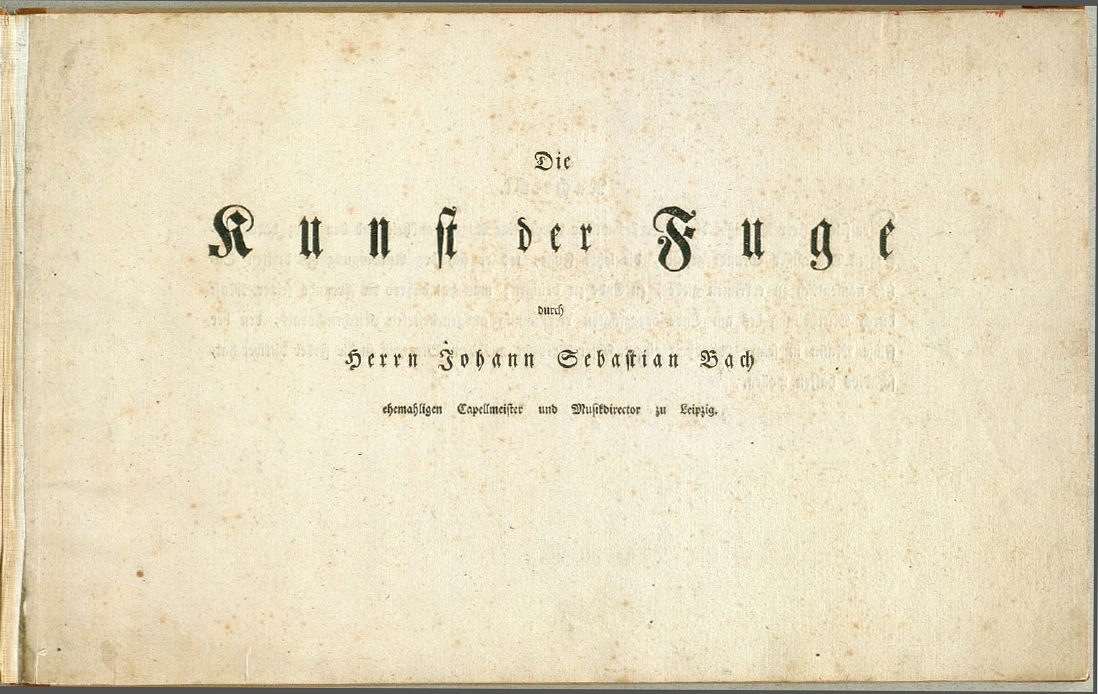

It’s a pity we couldn’t have had the kind of spoken introduction Hewitt gave in a New York performance, but there are always the notes to her 2012 Hyperion recording, in which she prefaces her specific observations with the assertion that she had at first been unexcited by the prospect of approaching The Art of Fugue. “The 'Goldberg' Variations and much of the Well-Tempered Clavier seem like child’s play in comparison,” she writes. “Its severity can be daunting, but also completely overwhelming, both intellectually and emotionally. And now I realize it is anything but boring.”

There was no fear of boring the listeners in an interpretation where every line speaks, or rather sings, for itself. Initial austerity is banished by harmonic waywardness, earth-shaking grandeur, playfulness, even humour. The definition was epitomised by the way Hewitt energetically lifts her hands off the keyboard at the end of each fugue (which also obviates the pedal "twang" you often get from the Wigmore Steinway). I might have guessed what she tells us about how she approached the work in her study, “singing each voice in turn and marking in the breathing points – which come at different times in different voices. There is no escaping that if you want it to make musical sense.” And human sense it made at every point, with spacious articulation and Hewitt’s own very careful dynamic grading (Bach provides none).  Two lofty cornerstones made us reel: Contrapunctus (as Bach calls each fugue) 6, with its high, lucid and proud double-dotted rhythms of the “stylo Francese”, its extended opulence, and Contrapunctus 11, taking us ever deeper into a maze with giddying chromaticism at its heart. All dodecaphonic 20th century music sounds boringly predictable alongside this. But there was also the sense of fun and games: the cuckoo thirds of Contrapunctus 4, and the not-so-unlucky 13, its dancing wit belying the mathematical genius with which Bach makes this mirror-reversible in its second rendition; as Hewitt writes, not only does he “turn this fugue upside down, he also turns it inside out: the top becomes the middle; the middle becomes the bass; and the bass becomes the top!”

Two lofty cornerstones made us reel: Contrapunctus (as Bach calls each fugue) 6, with its high, lucid and proud double-dotted rhythms of the “stylo Francese”, its extended opulence, and Contrapunctus 11, taking us ever deeper into a maze with giddying chromaticism at its heart. All dodecaphonic 20th century music sounds boringly predictable alongside this. But there was also the sense of fun and games: the cuckoo thirds of Contrapunctus 4, and the not-so-unlucky 13, its dancing wit belying the mathematical genius with which Bach makes this mirror-reversible in its second rendition; as Hewitt writes, not only does he “turn this fugue upside down, he also turns it inside out: the top becomes the middle; the middle becomes the bass; and the bass becomes the top!”

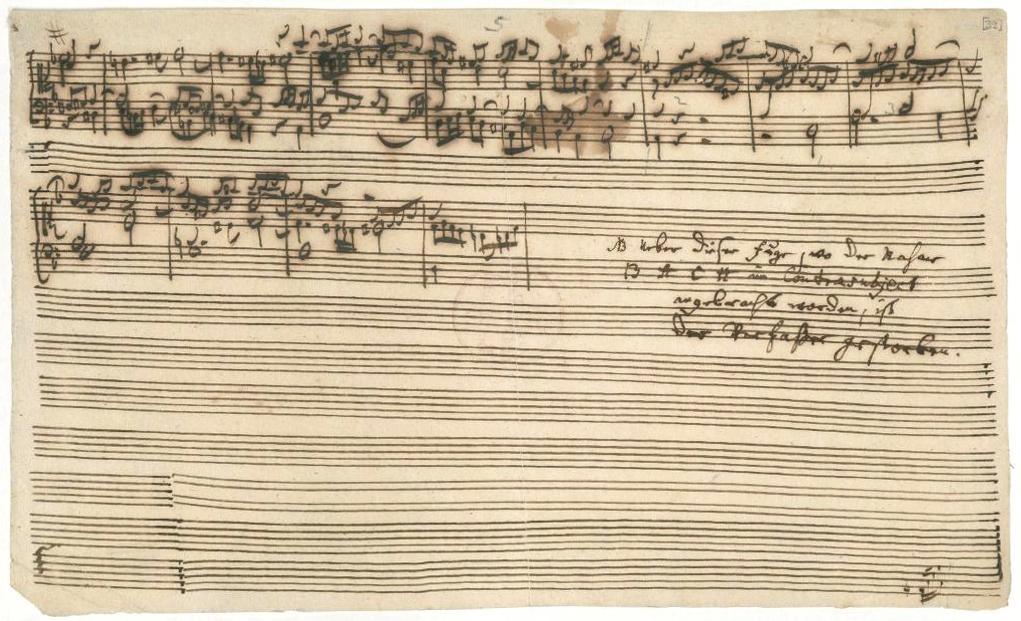

Would the two-voice canons introduce a note of detachment, of austerity? Not a bit of it: they “spoke” as well as the others, while at the same time providing the listener with some relief in clearly making out the lines. Clearly the crowning glory is Contrapunctus 14, taking us back to the heart of darkness that so often lightens in the course of a fugue. Only this one has three subjects, three distinct sections, the last of which spells out B (in German, B flat) A C H (the German B) before combining the three subjects. Plausibly, Bach would have added a fourth: the theme on which all the other fugues are based. He didn’t; was it as simple as laying down his pen and dying, as CPE Bach wrote on the score (pictured below), or did he leave the completion open to others?  It doesn’t matter: Hewitt’s trailing into a long silence, in which she seemed to be freeze-framed at the piano, gave us the goosebumps you can only get at a live experience – when would this end? The answer came with the gravely beautiful benediction based on the chorale “Before your throne I now appear”. Whether Bach dictated this on his deathbed, as legend has it, or not doesn’t matter; in Hewitt’s loving hands it gave the best possible blessing to an intensely human experience. If I end on a quibble, it’s only because I was jolted out of being in another place by the tones of the presenter, and it looked as if the pianist was too. Only applause matters after an experience like this, and even that’s an optional extra.

It doesn’t matter: Hewitt’s trailing into a long silence, in which she seemed to be freeze-framed at the piano, gave us the goosebumps you can only get at a live experience – when would this end? The answer came with the gravely beautiful benediction based on the chorale “Before your throne I now appear”. Whether Bach dictated this on his deathbed, as legend has it, or not doesn’t matter; in Hewitt’s loving hands it gave the best possible blessing to an intensely human experience. If I end on a quibble, it’s only because I was jolted out of being in another place by the tones of the presenter, and it looked as if the pianist was too. Only applause matters after an experience like this, and even that’s an optional extra.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Add comment