Barber Shop Chronicles, National Theatre at Home review - still lively after all these years | reviews, news & interviews

Barber Shop Chronicles, National Theatre at Home review - still lively after all these years

Barber Shop Chronicles, National Theatre at Home review - still lively after all these years

Barbershop banter and the place it occupies in black male identity

Barber shops – as we are all starting to appreciate in this time of lockdown – fulfil an emotional as much as a cosmetic role: having a haircut can represent a new beginning, a moment for reflection, or even an informal confessional.

It’s the playwright himself, Inua Ellams, who describes the barber shop as a “safe, sacred space where [British] black men can go to relax, escape racism and talk freely with no fear of being stopped, questioned or moved on by the police”. To write the play, he went to six different cities – Lagos, Accra, Kampala, Johannesburg and Harare as well as London’s Peckham – to witness the cut and thrust of barbershop banter and the place it occupies in black male identity.

It’s no small irony that Bijan Sheibani’s lively whirlwind of a production kicks off with the performers singing along to Skepta’s grime hit Shutdown. From this kick-ass opening we segue quickly into a scene in which a man called Wallace (Hammed Animashaun) is hammering on a Lagos hairdresser’s door at 6 in the morning shrieking “Help Me. Emergency”.

The emergency, it transpires, is that he needs a haircut. But the comedy is underscored by the more serious fact that as one of Lagos’s many unemployed (currently Nigeria’s unemployment rate is 23.1 per cent of the work force) he is penniless and desperate to get a job as a driver. When he bolts at the end of his haircut without paying, his story will become one of the many threads of Ellams’ boisterous and provocative narrative. Over the next one hour and forty-five minutes we will see the poor and the affluent, the straightforward and the corrupt, the furious and the easygoing take their seats and reveal the innermost workings of their hearts against the buzz of the clippers.

The emergency, it transpires, is that he needs a haircut. But the comedy is underscored by the more serious fact that as one of Lagos’s many unemployed (currently Nigeria’s unemployment rate is 23.1 per cent of the work force) he is penniless and desperate to get a job as a driver. When he bolts at the end of his haircut without paying, his story will become one of the many threads of Ellams’ boisterous and provocative narrative. Over the next one hour and forty-five minutes we will see the poor and the affluent, the straightforward and the corrupt, the furious and the easygoing take their seats and reveal the innermost workings of their hearts against the buzz of the clippers.

Rae Smith’s fluid design fills the stage with an array of chairs which can be spun quickly into new formations as the production flits from country to country. One moment we are in Nigeria listening to a rant about the divisions between the impoverished North and the wealthy South, the next we are in Uganda talking about the oppression of the gay population. Comedy and tragedy intertwine throughout. At one point a character riffs preposterously on the pros and cons of dating white women as opposed to black women, at another point the discussion revolves around the fact that while the Holocaust killed 6 million, slavery killed 30 million.

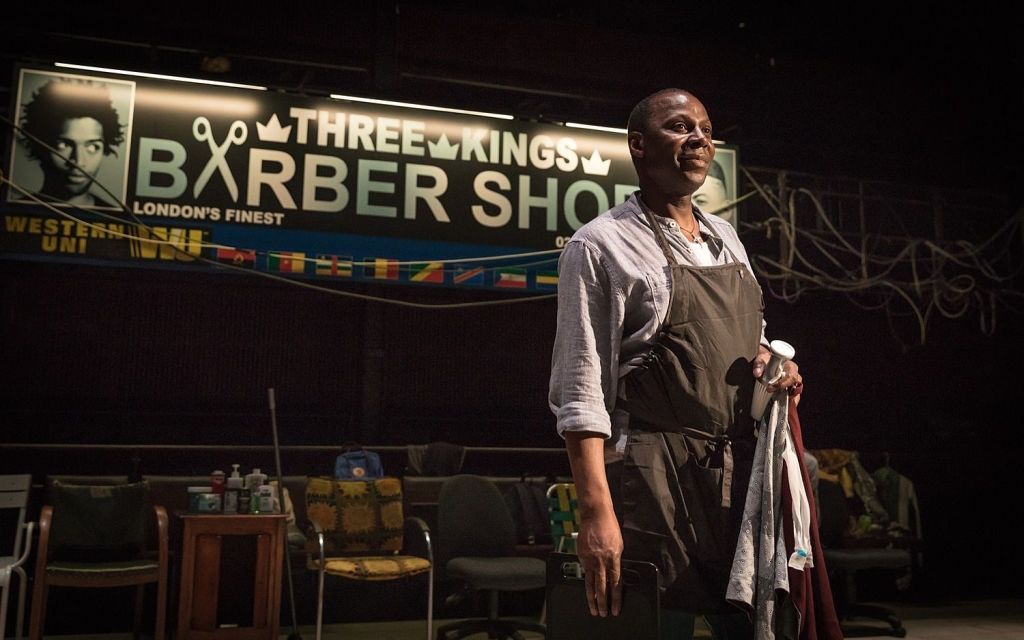

As the evening progresses – interspersed with music and dance interludes that include a routine where the dancers wheel around the stage on barber shop chairs – certain threads become more and more prominent. One recurring theme is that of domestic violence, another is the different ways of asserting identity through language (all the African countries featured are anglophone). The central narrative thread is that all the conversations are taking place on the day of a big football match between Barcelona and Chelsea. We eavesdrop on most characters before whirling on, though dramatic tension is stoked throughout by a dispute between Fisayo Akinade’s intense, troubled Samuel and Cyril Nri’s conflicted Emmanuel, Samuel’s employer (Nri is pictured above).

The vibrancy and humanity of this production come through in its online version, though it also makes you hunger to be there in the crowd. The noise and energy of the dance, the staccato irreverence of the banter, that sense of the multiple lives thronging through cities evoke the pre-Covid world all too vividly.

It’s yet another reminder that the compelling articulation of stories is the lifeblood of any culture, and the National Theatre (who co-commissioned this with Fuel) remains - if you'll excuse the pun - on the cutting edge of shaping the narratives of our time. Where William Blake saw a world in a grain of sand, Ellams shows it through several strands of hair, perhaps proving en route that – as a very different writer put it – “Hair is everything”.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

50 First Dates: The Musical, The Other Palace review - romcom turned musical

Date movie about repeating dates inspires date musical

50 First Dates: The Musical, The Other Palace review - romcom turned musical

Date movie about repeating dates inspires date musical

Bacchae, National Theatre review - cheeky, uneven version of Euripides' tragedy

Indhu Rubasingham's tenure gets off to a bold, comic start

Bacchae, National Theatre review - cheeky, uneven version of Euripides' tragedy

Indhu Rubasingham's tenure gets off to a bold, comic start

The Harder They Come, Stratford East review - still packs a punch, half a century on

Natey Jones and Madeline Charlemagne lead a perfectly realised adaptation of the seminal movie

The Harder They Come, Stratford East review - still packs a punch, half a century on

Natey Jones and Madeline Charlemagne lead a perfectly realised adaptation of the seminal movie

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

Add comment